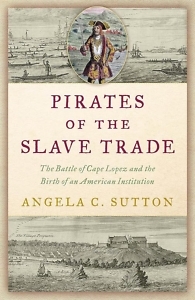

Piracy and Power

Angela Sutton recounts a pivotal battle in the history of the Atlantic slave trade

Not many people have heard of the Battle of Cape Lopez, fought off the coast of West Africa in 1722. But as Angela Sutton demonstrates in Pirates of the Slave Trade, this battle accelerated the forces that were transforming the Atlantic slave trade. Her stirring narrative history follows a cast of West African kings, notorious pirates, and cold-blooded officers of the British Royal Navy, while illustrating changes that had serious consequences for American history.

Angela Sutton is the assistant dean for Graduate Education and Academic Affairs and an assistant research professor at Vanderbilt University. She is the director of the Fort Negley Descendants Project, an oral history archive of descendants of the enslaved who built and defended a Civil War fortification on the UNESCO Slave Route. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Angela Sutton is the assistant dean for Graduate Education and Academic Affairs and an assistant research professor at Vanderbilt University. She is the director of the Fort Negley Descendants Project, an oral history archive of descendants of the enslaved who built and defended a Civil War fortification on the UNESCO Slave Route. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: One of the most fascinating figures in your book is John Conny, the leader of the Akan people in the early 18th century. How did he amass such power? What did that power suggest about the state of West African politics in his time?

Angela Sutton: African leaders — like the Ahantan of infinite names, who I call John Conny in the book — was a multilingual broker with a large family and kinship network. As a child, he witnessed his people struggling with ship after ship of various European arrivals who made promises and then sowed divisions which laid African villages to waste. As a young man, he was sent north to live in Fanteland with distant relatives to amass the widest set of skills. Like other powerful West Africans on the coast, he became a savvy businessman and martial leader, well versed in various African and European cultures and languages, with eyes everywhere. He knew far more about them than they knew about him.

To the diverse cultures in West Africa, Europeans were considered just one more ethnic group to work into the political and social dynamic. Europeans who did not try to understand West Africa’s cultures and languages or offer mutually beneficial business arrangements found themselves on the outs, or worse.

Chapter 16: The pirate “Black Bart,” you write, got his start as “an ordinary man trapped in a dangerous and distasteful yet unextraordinary life.” How did he become such an infamous figure? How was piracy shaping the slave trade?

Sutton: During this late stage of the Golden Age of Piracy, pirates had been forced to the fringes of empire. They fled the pirate hunters of the Caribbean and descended upon West Africa. What they found there was misery: worm-eaten ships, captained by bitter traders, full of desperate captives in various stages of poor health and doomed for sale in the Americas. The pirates switched focus from plundering toward increasing their numbers at exponential rates.

If Black Bart’s story teaches us anything, it’s that circumstances can often dictate the course our lives. Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts was one of thousands of sailors with navigation skills who had been propelled by life circumstances into an oppressive job with one of the highest turnover rates. When the slave ship he was on was taken by pirates, he leaped at the opportunity to leave behind a life of coercion and begin a life of self-determination, bringing the slave trade to a standstill.

Chapter 16: What happened at the Battle of Cape Lopez? What was its impact?

Sutton: The Battle of Cape Lopez occurred off the coast of Gabon, West Africa, in 1722. It was between the British Navy and Black Bart’s fleet. The pirates had spent the previous year and a half terrorizing the West African coastline while being hunted by the Navy, destabilizing the trade just as demand for enslaved labor increased in the Americas. Once these pirates had been caught and “summarily dealt with,” Britain’s royal slave trading company was able to rebuild the trade and export unwilling captives at exponentially greater rates to its territories in the Americas, including the North American colonies which would become part of the United States. This exponential growth in the trade of enslaved Africans to the Americas allowed the newer British model of slavery — chattel slavery — to become the predominant form of enslavement in the U.S.

Chapter 16: One theme that keeps surfacing in Pirates of the Slave Trade is how British accounts depict West Africans. How did this first draft of history shape a popular understanding of the slave trade?

Sutton: One of the slave traders whose records I rely on, William Snelgrave, was among the staunchest anti-abolitionists in Great Britain at the time. His father had been a slave trader to Virginia, and young William was proud to follow in his footsteps. He took prolific notes about what he witnessed in West Africa and cast himself as the hero of every story he inserted himself into. These notes were then published into travelogues, which had a wide and popular following. Snelgrave is responsible for the creation of many of the tropes of “savagery” that Europeans came to associate with Africans: He delighted in the horrors of cannibalism, ritual human sacrifice, nakedness, torture, wartime atrocities, etc.

Sutton: One of the slave traders whose records I rely on, William Snelgrave, was among the staunchest anti-abolitionists in Great Britain at the time. His father had been a slave trader to Virginia, and young William was proud to follow in his footsteps. He took prolific notes about what he witnessed in West Africa and cast himself as the hero of every story he inserted himself into. These notes were then published into travelogues, which had a wide and popular following. Snelgrave is responsible for the creation of many of the tropes of “savagery” that Europeans came to associate with Africans: He delighted in the horrors of cannibalism, ritual human sacrifice, nakedness, torture, wartime atrocities, etc.

He also was a perpetuator of the idea that enslavement could be beneficial to Africans: that the heroic British slave traders had a duty to liberate Africans from savagery and bring them into Christendom, where they could live honest lives of purposeful work, protected by benevolent enslavers. As we’ve now seen with the most unsavory elements of the [political] right, this view resurfaces regularly with regard to Black Americans.

Chapter 16: Researching this book took you to archives throughout Europe. What are the main challenges in writing this history? Do the sources present limitations?

Sutton: History is created from primary sources that were deemed important enough to write and to preserve. The slave trade transformed our society to devalue Africans and their descendants in every way. The vast majority of enslaved people were barred from learning how to read or write, and those who could often had no access to the structures of power that collected and preserved written material for inclusion in the archives on which historians depend. For me, it means that when I read the words of European enslavers and human traffickers, I must use oral histories, geography, archaeological evidence, and triangulation of European sources (Dutch, English, Prussian, and Swedish) in an attempt to reconstruct that which white supremacist society has kept from us.

I tried to make this process explicit in the book. Often the book takes a conversational tone as I discuss where the sources disagree, what went unwritten or unmentioned in the sources, and what those omissions could mean. I made that choice because doing so allows for a fuller story to emerge. In this story of the Battle of Cape Lopez, you’ll find stories of resistance, along with counter-narratives to African “savagery” and body-horror. In several places, I invite the reader to follow the documentary trail to see if the conclusion matches what the loudest and whitest voices at the time recorded about this period.

Chapter 16: How did the British control of Atlantic slave trade shape ideas about slavery and race? How might that continue to affect the United States?

Sutton: Prior to the Battle of Cape Lopez, most of the Atlantic world’s systems of enslavement followed models inspired by ancient Rome, where enslavement was a temporary state of being, and not a permanent, race-based identity that could be passed in perpetuity to one’s descendants. Under the economically efficient chattel model, which the United States adopted, enslaved people were rendered as objects legally, with no human rights. This caused the wider society to normalize the idea that some people didn’t have to be extended rights or treated like humans. Once we did that with the enslaved, it created precedent that made it easier for our society to do this to other populations in the U.S.: Indigenous peoples, queer people, incarcerated people, women, religious minorities, undocumented people, you name it.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.