Play That Thing

Tap into the remarkable powers of the typewriter

I have an old manual typewriter in my living room, for the same reason some people have a piano in theirs — I love music.

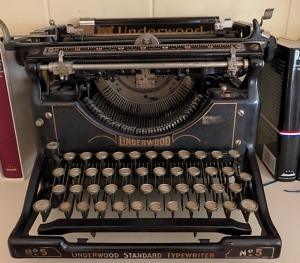

Sometimes I’ll tap the keys as I walk by, a little rat-a-tat of random notes, that song of the typewriter, at once jaunty and stern, and as musical to me as a song by Fats Waller. I love typewriters, and especially my old Underwood model No. 5, a century or more old, and a gift from my mother, said to be a demon on the keys in her secretarial days.

Or maybe not so much a gift, as a gag: The letter and number keys of the old family Underwood are blank. It’s a teaching model for students learning to touch-type — something I never did, despite a lifetime at the keys.

Typing classes in high school and college. Thirty-five years as a newspaper reporter and editor. Another four spent writing stories for a non-profit before retiring. And all the while and still, early every morning, tapping away on my own writing, my fiction, at home.

How many letters struck? Millions? Ten of millions?

And yet the keyboard — of the manual and then electric typewriters on which I began and the laptop (alas) on which I necessarily continue — remains a muddle. So I keep it simple, using only my index fingers. I hunt and peck. Well, seek and destroy. I tend to bash the keys so hard the letters disappear from those most frequently struck. And yes, I see the irony of those keys blankly staring me down, mocking me.

But back to my living room, because this isn’t about typewriting. This is about typewriters, surely one of our greatest inventions — as simple to work as the wheel, as I’ve proven in all my whack-a-vowel glory; and yet, considering what the likes of William Faulkner and Eudora Welty created with its help, as strong as steel, powerful as a freight train, illuminating as a light bulb.

Name me an American invention that surpasses the typewriter. OK, jazz. You’ve got me there.

Or do you? Because typewriters are music — or anyway, musical — as sure as our most lyrical writers are musicians and typewriters their instruments. Consider Welty and her remarkable story “Powerhouse.” She attended a Fats Waller performance in her hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, in 1940. She came home so excited she wrote a story about it, Fats becoming the fictional Powerhouse:

“Aaaaaaaaa!” shouts Powerhouse, flinging out both powerful arms for three whole beats to flex his muscles, then kneading a dough of bass notes. His eyes glitter. He plays the piano like a drum sometimes — why not?

“I wanted to express what I thought of as improvisation,” she said, in a decades-later interview, explaining how she wrote about the band members’ interactions, the call-and-response of their conversations.

Improvisation — that’s jazz talk.

“I never would have set out to do ‘Powerhouse,’” she said in another interview, “because I wouldn’t have thought I could. I was just so keyed up that I just did it.”

And then Welty, who liked to write in a rush and revise to her heart’s content, who loved revision, let this one stand. She knew better than to try and tinker. “Powerhouse” was of and in the moment — not just a story but a performance, as much as the one she’d witnessed by Fats and his band.

And then sometimes, the typewriter literally is a musical instrument. It’s heard, along with tin whistle and mandolin, in the Pogues’ “Down All the Days,” an ode to the Irish writer Christy Brown, born with cerebral palsy and only able to type with the toes of his left foot. The sound of a typewriter likewise appears in the aptly named “Wordy Rappinghood” by Tom Tom Club. No wonder Joni Mitchell, in “Edith and the Kingpin,” sings: “The band sounds like typewriters.” Or, alternatively, that the title “the William Faulkner of jazz” was bestowed upon a piano player, Mose Allison.

So typewriters are tools. They’re music. They’re also art — steampunk before it was a word. Ah, typewriters — their Art Deco curves, their dark noir-film cool. Except, of course, when they’re bursting with color: pink or seafoam green or the smoky gold of the gorgeous 1938 Continental Klein Conti. (You see a picture of the latter and think, Oh, that used to be God’s typewriter. Or Little Richard’s.) And those names: Contessa, Blue Bird, the Baby Fox!

There’s an American sculptor named Jeremy Mayer. He disassembles typewriters and remakes the stuff and guts into startling figures: crows, owls, an allosaurus.

But I wouldn’t let him near the old family Underwood. It’s perfect as is, on the bottom shelf of our living-room bookcases, flanked by Faulkner and Welty — my favorites typists, if you will.

You can visit the Mississippi homes of both — Faulkner in Oxford, Welty in Jackson — and in your rummaging are reminded of what everyday lives they lived, and also what they loved beyond words — Welty her garden; Faulkner, by the look of his well-worn boots, riding horses. But there’s a holy moment when you see the secular sacred of their work spaces. And center of it all, in these working shrines — the typewriter.

Not to make too much of the thing, of course. Faulkner would have clawed The Sound and the Fury out of stone, if he had to. I’m typing this on a laptop; the old family typewriter needs refurbishing, and everybody wants digital submissions these days. As for Welty, she didn’t care how she got her words down. Sometimes she wrote longhand. But as she told a Memphis newspaper, The Commercial Appeal, in 1977, “I like to type fairly soon (after writing something) so I can look at it objectively on the page.”

Because a sentence, typewritten, can be trusted. The letters stand at attention, no slouching. All the better to be seen for just what they are, to be judged. I like to think, also, that a typewritten word is, like a flower, straining for the sun, the light — an image Welty, of the lovely garden, would like.

That’s the wonder of the typewriter. It’s a tool that’s a bit of a muse. It’s a tool that can be used to create worlds and explain our very existence, even if it seems we’re only clattering away like those hypothetical simians of the infinite monkey theorem.

Hunt and peck. Seek and destroy. No matter. You’ll get there. Letters will become words, and words, arranged just so, can change minds and lives. Or not.

If words fail, make music.

Copyright (c) 2025 by David Wesley Williams. All rights reserved.

David Wesley Williams is the author the forthcoming novel Come Again No More (JackLeg Press, 2025), as well as the novels Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, 2023) and Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, 2013). He lives in Memphis.