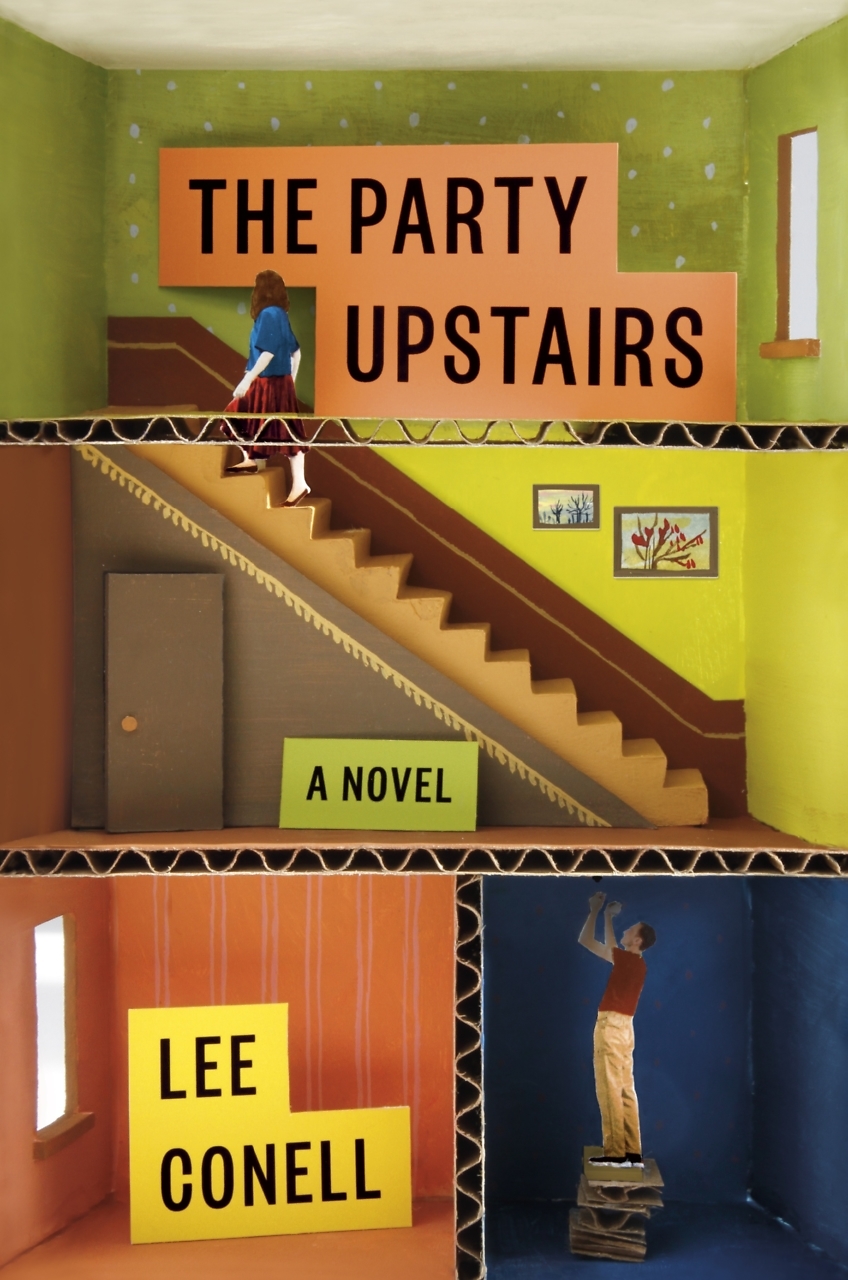

Poet for the People

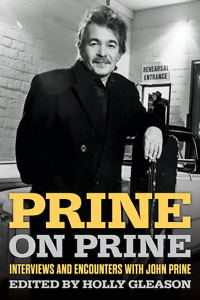

Prine on Prine shines with the beloved songwriter’s heart, humor, and humanity

There were many John Prines. We were lucky that way. There was Prine the young folkie and “New Dylan,” but with songs even Bob couldn’t write: “Angel from Montgomery,” “Hello in There,” “Sam Stone.”

There was Prine the rocker, looking louche on the cover of Sweet Revenge, and sounding it on the opening lines: “I got kicked off of Noah’s Ark / I turn my cheek to unkind remarks / There was two of everything, but one of me.” There was rockabilly Prine, produced in Memphis by Sam Phillips’ sons, with a little help from the old man. Country Prine, dueting with Connie Smith. And in the later years, having survived cancer and the fickle whims of culture, there was Prine the legend, beloved for his wit and humanity — and still with a stellar album in him at age 71.

They were all great. And they’re all here in Prine on Prine, a collection of interviews (with a man who hated to be interviewed, not that you can tell) and “encounters,” as the subtitle puts it, edited by veteran music critic and Prine friend Holly Gleason.

The book spans 50 years and features the likes of film critic Roger Ebert, famed interviewer Studs Terkel, music critics Robert Hilburn and Robert Christgau, then-U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser, and Dave Cobb, who produced Prine’s late-life gem of an album, 2018’s The Tree of Forgiveness. There are stories, straight Q&As, radio and TV transcripts, excerpts from a movie script, even recipes.

Over the course of 300-plus pages, we meet all those Prines. But mostly we hang with the one and only John — poet of the people, patron singer of the human condition, able to make us cry, laugh, feel a little less lonely, and follow him anywhere (from Montgomery to Muhlenberg County, from heaven to the “dog-racing side of town”).

And fame? Glory? Nah, none of that, please. He didn’t play that game, had no interest in making the same album again and again to suit the market. Formula is for pop singers and soft drinks. Prine was like Dylan, going where the music took him, whether anyone followed or not. As Gleason writes in her introduction:

What doesn’t get nearly enough attention is his seeking musical restlessness. Intimate folk records. Grinding ravers. Soul-undertowed songwriter fare. Summer campfire standards. Myriad dance rhythms. Old-school Southern gospel. Horn blasts. Steel guitar that melts over the tracks. Electric guitars that both buzz and twirl.

In other ways, he was the anti-Bob. Dylan’s inscrutable, Prine was open. Approaching Dylan in public might require some nerve — not for nothing is he known for disguises. But Prine was welcoming — at least he was that night I spied him across the lobby of The Peabody hotel in Memphis, a few hours after seeing him play the Beale Street Music Festival. Finally, where Dylan’s humor tends to bite, Prine’s was more likely bemused. Not that Prine would put himself in such exalted songwriting company, mind you.

Here’s a telling passage from Lloyd Sachs’ 2005 piece in No Depression magazine, on how such a young man wrote those deep, knowing and empathetic songs on his debut album, John Prine:

“Hey, I just figured I knew about what I was writing about, but that doesn’t make me smart,” said Prine. “To be able to have those insights about people, that doesn’t mean you have any answers. All you’re able to do is give the police a good description of the guy who robbed the place.”

As for the Dylan comparisons, Prine would say the better comp would be someone from the country field — or, in a nod to his family’s Kentucky roots, bluegrass legend Bill Monroe. Well, sort of: “I always figure that if Bill Monroe didn’t know how to play quite so good and would sing a little off-key, we might sound a little more like each other,” he told Bob Millard for a Country Song Roundup magazine story in 1985.

As for the Dylan comparisons, Prine would say the better comp would be someone from the country field — or, in a nod to his family’s Kentucky roots, bluegrass legend Bill Monroe. Well, sort of: “I always figure that if Bill Monroe didn’t know how to play quite so good and would sing a little off-key, we might sound a little more like each other,” he told Bob Millard for a Country Song Roundup magazine story in 1985.

His singing and playing suited his songs just fine, of course. A smooth, pretty voice and flashy picking would just get in the way of lines like, “She was a level-headed dancer, on the road to alcohol,” or “The air’s as still as a throttle on a funeral train,” or (insert your favorite here).

Ah, those songs. They’re some of the best we’ll ever have.

But Prine didn’t just entertain us. He enriched us. He enriches us still, with the music he left. He shows us how to laugh at our follies. He shows us that a sense of humanity isn’t just important to our survival in this “big, old, goofy world” — it’s practically all that matters. In this wonderful book, he shows us all that — and also how to make his favorite cocktail, the Handsome Johnny.

So I think you know what to do now. But if somehow not, allow me a paraphrase of that famous chorus from an early Prine classic, “Spanish Pipedream”:

Blow up your TV, throw away your cell phone

Go to a bookstore, buy you this tome

Put on “Paradise,” or one about heaven

Try and find John Prine on your own

He’s here, our old friend, on every page.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novels Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, 2023) and Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, 2013). His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.