Poet Laureate of Point Breaks

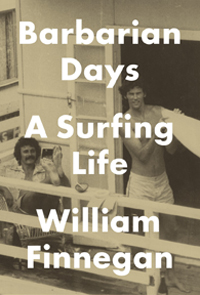

Barbarian Days is an elegant ode to surfing by New Yorker writer William Finnegan

“Waves were the playing field,” writes William Finnegan. “They were the goal. They were the object of your deepest desire and adoration. At the same time, they were your adversary, your nemesis, even your mortal enemy. The surf was your refuge, your happy hiding place, but it was also a hostile wilderness—a dynamic, indifferent world.” This bit of surf philosophy—along with much of the tone and content of Finnegan’s new memoir, Barbarian Days—reads like something Ernest Hemingway might have written if he’d been born in 1950s Southern California.

The comparison is apt: like Hemingway, William Finnegan spent much of his youth traveling the world in search of dangerous adventure and literary inspiration. Also like Hemingway, he has written dispatches from hazardous conflict zones. And with Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, Finnegan has done for surfing what Death in the Afternoon did for bullfighting: he explains, quite elegantly, how an esoteric, peculiar passion can provide a vehicle for forging meaning in an apparently meaningless world. He also argues for the way the greatest practitioners of that obsession achieve something approaching transcendence and, at least in the eyes of adventure junkies, immortality.

The comparison is apt: like Hemingway, William Finnegan spent much of his youth traveling the world in search of dangerous adventure and literary inspiration. Also like Hemingway, he has written dispatches from hazardous conflict zones. And with Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, Finnegan has done for surfing what Death in the Afternoon did for bullfighting: he explains, quite elegantly, how an esoteric, peculiar passion can provide a vehicle for forging meaning in an apparently meaningless world. He also argues for the way the greatest practitioners of that obsession achieve something approaching transcendence and, at least in the eyes of adventure junkies, immortality.

In the late 1980s, when William Finnegan started filing dispatches for The New Yorker from the world’s hottest conflict zones, readers could not have known that this fearless and gifted reporter had honed his skills not in journalism school but by spending most of his early adulthood travelling the globe in search of the perfect wave. “Here I was writing, often contentiously, about poverty, politics, race, U.S. foreign policy, criminal justice, and economic development, hoping to have my arguments taken seriously,” Finnegan writes. “I wasn’t sure that coming out of the closet as a surfer would be helpful.”

Finally, in 1992, he wrote “Playing Doc’s Games,” a two-part essay about Northern California surf culture centered on Mark “Doc” Renneker, a legendary and legendarily divisive San Francisco physician and big-wave surfer. Rather than undermining Finnegan’s reputation as a reporter, the article was hailed as a masterpiece, admired less for its portrait of Renneker than for its deeply personal exploration of Finnegan’s own conflicted attitude toward surfing’s allure. With his long-awaited memoir Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, Finnegan makes his full confession, simultaneously delivering an engrossing chronicle of growing up wild and free in California and Hawaii, a rhapsodic road adventure, and a magnificent account of the all-encompassing power of a singular obsession.

One of the many great pleasures of this remarkably absorbing book—and there are many—is the window Finnegan opens to the lost world of Pacific coastlines before the real-estate boom, as well as the lost freedom of youth before the rise of the helicopter parent. Finnegan came of age in the late 1950s, when surfing was hot but the best breaks were not yet so crowded that a young boy couldn’t find his place in the lineup, when parents pushed kids out the door in the morning and didn’t worry about what they were doing between breakfast and dinner, when black eyes and broken bones were just part of growing up. Finnegan recounts with sometimes heartrending lucidity the mixed blessing of moving as an adolescent to Hawaii for his father’s career as a television producer. All at once, young Bill finds himself both living only a few hundred yards away from a great surf spot and flung into a rough public school where, as a non-native Hawaiian, or “haole,” he’s forced to fight almost every day.

“I’m struck by how much violence defined my childhood,” Finnegan writes. “Nothing lethal, nothing horrifying, but basic to daily life in a way that seems archaic now.” Finnegan gets tough at school and finds solace in the ocean, where he gradually comes to grips with his own essential attraction to danger: “Surfing had, and has, a steel thread of violence running through it. I don’t mean the roughnecks one encounters in the water—or, very occasionally, on land, challenging one’s right to surf some precious spot,” he writes. “No, I mean the beautiful violence of breaking waves.” He calls this power “the critical element, the essence of what we are out there to find, to test ourselves with—to recklessly engage or cravenly avoid.”

“I’m struck by how much violence defined my childhood,” Finnegan writes. “Nothing lethal, nothing horrifying, but basic to daily life in a way that seems archaic now.” Finnegan gets tough at school and finds solace in the ocean, where he gradually comes to grips with his own essential attraction to danger: “Surfing had, and has, a steel thread of violence running through it. I don’t mean the roughnecks one encounters in the water—or, very occasionally, on land, challenging one’s right to surf some precious spot,” he writes. “No, I mean the beautiful violence of breaking waves.” He calls this power “the critical element, the essence of what we are out there to find, to test ourselves with—to recklessly engage or cravenly avoid.”

The family eventually returns to California, but the seed of Finnegan’s future life has been sown. He spends his late teens vacillating between competing interests—surfing, writing, an intense relationship with a brilliant, beautiful girlfriend—before embarking on an open-ended international surf odyssey that would take him from Hawaii to Guam, Indonesia, Fiji, Portugal, and eventually to Cape Town, South Africa. There he took a job as a high-school teacher in an all-black township just as the eyes of the world had begun to focus on the moral outrage of apartheid, an experience that reawakened his latent literary and political consciousness. Though the young Finnegan frequently bemoaned the extent to which his surf addiction led him to waste his life, it’s easy to see how this young surfer’s combined thirst for risk and purity led him toward a career as a war correspondent and commentator on international affairs, bearing witness to some of history’s critical dramas and crises.

Nevertheless, most of Barbarian Days takes place at one beach or another. At times the book reads like a detailed diary of every set of waves Finnegan ever lined up during more than forty years of dedicated surfing, but he somehow manages to wax poetic again and again on the same subject with nuance and variety. Surfers will no doubt nod appreciatively, occasionally gobsmacked by the lyricism of Finnegan’s writing. Less knowledgeable readers may occasionally feel their eyes glazing over as they approach yet another passage of rapturous wave worship, only to be whipped back to attention by a shimmering turn of phrase or insight. Take, for instance, a glorious day at a once-secretive spot in Fiji called Tavarua, now regarded as one of the world’s most coveted breaks:

At six feet it was easily the best wave either of us had ever seen. Scaled up, the mechanical regularity of the speeding hook gained soul, its roaring sparkling depths and vaulted ceiling like some kind of recurring miracle, the tracery on the surface and the ribbed power in the wall full of delicate, now visible detail, each wave suffused with the richness of a one-off. Sometimes the wind swung east, blowing into the hook and sending a hard chop up the face, particularly in the last hundred yards to the channel. When the wind blew south or southwest, it came around the west side of the island, making a mess of the waves as they approached us on the half-mile-long wrap from the southern edge of the reef. But then they cleaned up suddenly as they made the last turn into the lineup, and the slingshot aspect of the wave was doubled by a trailing wind that slipped under your board and whispered, Go.

In moments like these, any argument about the relative merit of spending one’s life chasing the horizon in search of an all-too transient experience fades away, replaced by something approaching the sublime.

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, will be published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.