Polished Jewels

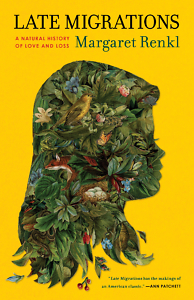

Margaret Renkl weaves personal and natural history in Late Migrations

There must have come a moment, somewhere during the writing of Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss, in which Margaret Renkl was asked to describe her work-in-progress. And I would like to have been there when she did, to see the doubt and bafflement torque the listener’s face. For how can any brief description capture this entirely original and deeply satisfying book? I’ve read it twice now, with deepening wonder, so I’ll try.

The 112 short-form nonfiction pieces collected in Late Migrations vary in length from a paragraph to a few pages. More than a dozen illustrations by artist Billy Renkl, the author’s brother, are scattered among them. The opening, “In Which My Grandmother Tells the Story of My Mother’s Birth,” is set in “Lower Alabama, 1931” and rendered as if spoken by the grandmother. The book’s subsequent piece — Renkl’s description of her efforts to entice bluebirds to her garden — seems unrelated. This pattern continues throughout the book: place-based narratives about Renkl’s family that move forward chronologically, alternating with her idiosyncratic backyard-naturalist meditations.

How can these threads possibly be woven? Ah, that’s the surprise and accomplishment. Individually, the pieces are polished jewels, and indeed 10 of them have been published in The New York Times, where Renkl is a contributing opinion writer. (She’s also the former editor of Chapter 16.) But the discrete pieces gain depth and resonance from accrual. The parents on the Alabama peanut farm are the same ones who comfort homesick Renkl when she drops out of her ill-fitting grad program in the urban North, and they’re the same ones who later switch roles with Renkl as she becomes their caregiver.

These passages, in which she first nurses her father through his slow death and then endures her mother’s sudden one, are some of the most moving in the collection. We know from an earlier essay that the ashes of the cremated father were never buried. Renkl’s mother asks to be cremated too, but, because there’s no room left in the family plot, she’ll need her children to wedge them both in with the help of a posthole digger. In “Ashes, Part Three,” the children carry out the mother’s wish: “They are buried now in the graveyard between the church where Mom was baptized and the schoolhouse where she learned to read.”

The natural histories complement and enlarge the personal ones. Renkl’s wry appraisal of both human and nonhuman animals is affectionate yet unsentimental. From the Nashville suburbs where she lives, she describes the beauty of the lily pads on a pond before she reveals that, as an invasive species, they are choking the pond to death. She doesn’t villainize the male cardinal who dives “like a tiny strategic bomber” to chase her beloved bluebirds from the feeder, knowing that, “in late summer, the season of plenty gives way to the season of competition.” She tallies the animals’ territorial aggressions: “[T]hough there is plenty to go around … for them, scarcity is no different from fear of scarcity. A real threat and an imagined threat provoke the same response. I stand at the window and watch them, cataloging all the human conflict their ferocity calls up.”

The natural histories complement and enlarge the personal ones. Renkl’s wry appraisal of both human and nonhuman animals is affectionate yet unsentimental. From the Nashville suburbs where she lives, she describes the beauty of the lily pads on a pond before she reveals that, as an invasive species, they are choking the pond to death. She doesn’t villainize the male cardinal who dives “like a tiny strategic bomber” to chase her beloved bluebirds from the feeder, knowing that, “in late summer, the season of plenty gives way to the season of competition.” She tallies the animals’ territorial aggressions: “[T]hough there is plenty to go around … for them, scarcity is no different from fear of scarcity. A real threat and an imagined threat provoke the same response. I stand at the window and watch them, cataloging all the human conflict their ferocity calls up.”

Renkl is a clear-eyed observer. She’s also a gorgeous writer. She captures the endless summers of a red-dirt-road childhood in which “autumn is inconceivable to us. School will be reinvented every year, an astonishment every year.” Her sentences are charged by metaphors. The chipmunks who infest the crawl space under her house aren’t social creatures but solitary, “each keeping to its personal private entryway into the dark.” She amplifies: “They are like neighbors who check the mailbox from the car and then drive straight into the garage, never a friendly word.” Sometimes she’ll construct long lyric sentences in which each phrase could stand alone as a tiny poem. For example, a lush litany of things she passes on a walk includes “all the sunning turtles lined up on their black logs like rosary beads.” An image that apt is just stuck in the middle of a sentence; she’s at ease and unstingy with her presents.

And speaking of presents, I can’t help but compile a list of people I want to gift with Late Migrations. I want them to emerge from it, as I did, ready to apprehend the world freshly, better able to perceive its connections and absorb its lessons. Ready, finally ready, to heed Renkl’s advice:

“In the stir of too much motion:

Hold still.

Be quiet.

Listen.”

[This article originally appeared on June 24, 2019.]

Beth Ann Fennelly, the poet laureate of Mississippi, teaches in the MFA Program at the University of Mississippi. Her sixth book, Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs, was recently published by W.W. Norton.