Praise Song

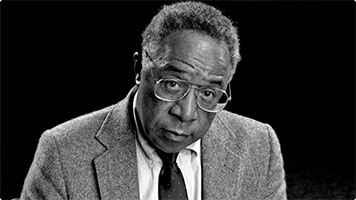

On the fortieth anniversary of the publication of Roots, poet Nikki Giovanni remembers the hope Alex Haley offered at a perilous time

I was born in Tennessee in the old Knoxville General Hospital. I was the first person in my family born in a hospital. When my sister and cousins and I would argue, they would say, “You don’t even belong to us.” I don’t think I believed them but I did look at my family in a different way, sort of. I knew they were just being mean, but I also thought, Well, what if they’re right? What if I was picked up by accident? What if I belonged to someone else?

We moved from Knoxville to Woodlawn, Ohio, which is north of Cincinnati. This was during the age of segregation. My mother and father had jobs which had not been possible in Knoxville. We rented a two-bedroom house: kitchen, sitting room, and we had an outhouse. I remember the outhouse and, for reasons I don’t understand, have a fondness for that memory. In fact, when I bought my own home I had Dan to make an outhouse out front to collect my mail. It’s a sentimental thing.

We moved from Knoxville to Woodlawn, Ohio, which is north of Cincinnati. This was during the age of segregation. My mother and father had jobs which had not been possible in Knoxville. We rented a two-bedroom house: kitchen, sitting room, and we had an outhouse. I remember the outhouse and, for reasons I don’t understand, have a fondness for that memory. In fact, when I bought my own home I had Dan to make an outhouse out front to collect my mail. It’s a sentimental thing.

We were poor. That’s understood. When my parents saved enough money to purchase a home in Lincoln Heights, a segregated community just outside Cincinnati, we all felt we were big stuff. Lincoln Heights didn’t have garbage collection, so we had to burn our garbage. I loved it. The lot next door was empty, and I remember the rabbits lived over there. Probably other things, too. I would chase the rabbits but I was never successful. I only wanted to play with them but they didn’t understand that. I guess all they knew about me was that I burned garbage every night. I would stand and watch the fire. I don’t think I worried so much about burning the house down as I was simply fascinated by fire. Some evenings I watched the moon. Mostly I remember just dreaming.

Mommy taught third grade at St. Simon’s School. Gus, my father, taught math at Lincoln Heights Middle School. One day, for reasons totally unknown or not remembered, I decided to meet Gus, who walked up the hill every day to our home. I had a blue bike. As I started down the hill I seem to remember or thought I heard Gus say, “Look at that crazy kid coming down the hill.” By that time the bike was actually riding me. I still, at seventy-two, have scars from that.

But I survived.

I’m trying to understand my father. A part of me thinks he was mean; a part thinks he drank too much; a part just doesn’t understand. But every Saturday night about 11 p.m., if you asked what I was doing, I was hearing my father beat my mother. The saddest sound I ever heard one night was, “Gus, please don’t hit me.” It was a prayer.

I had an older sister but she was always friendly. She had girlfriends that she would spend the weekend with. She would come home Sunday late and talk about what a good time she had. I am not friendly. I stayed home. Until I couldn’t stay any more. My godmother, Baby West, died and left me fifty dollars. I walked to the bank in Lockland to see what I could do with it. I could take it, they said. I purchased a Butterfinger and a ticket to Knoxville. Our neighbor, Mr. Gray, who must surely have known what went on in our home, gave me a ride to the train station.

I had an older sister but she was always friendly. She had girlfriends that she would spend the weekend with. She would come home Sunday late and talk about what a good time she had. I am not friendly. I stayed home. Until I couldn’t stay any more. My godmother, Baby West, died and left me fifty dollars. I walked to the bank in Lockland to see what I could do with it. I could take it, they said. I purchased a Butterfinger and a ticket to Knoxville. Our neighbor, Mr. Gray, who must surely have known what went on in our home, gave me a ride to the train station.

Grandmother must have known what I was trying to get away from yet we never even discussed it. I asked if I could stay with them. She and Grandpapa didn’t hesitate: Yes.

I read now about the need for black boys to have fathers in the homes, and I wonder. White boys have fathers at home, and they end up in the KKK. The white boys end up calling us names. Spitting at us and worse. Now the white boys are policemen shooting unarmed fourteen-year-olds to death. Or they are billionaires running for president. Stirring up hate. I’m not sure fathers are necessary beyond their biological function. If we are going to criminalize women for abortions, shouldn’t we also criminalize the men who impregnated them?

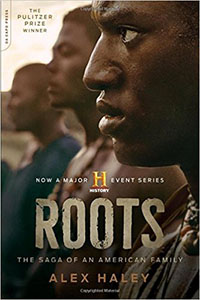

But we have a larger question. Alex Haley said we have Roots. He traced his back to Africa. What I really understand about my Roots is that the black woman mated, willfully or not, with the life form on this land they were brought to. No matter its color, race or religion. That life form would now like to deny its responsibility. But the black woman loved that which she incubated. And, for the most part, brought it forth to believe in the future.

Alex Haley did a good job. He reminded us of hope. All I’m saying is that everything has Roots. Our only question is, do we pull them up like weeds to be destroyed, or do we nurture them to allow them to blossom? I knew Alex Haley. He gave us, at a perilous time, reasons to go forth. He reminded us we all have Roots. Our human, our humane, job is to entwine and enrich.

Poet Nikki Giovanni was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, on June 7, 1943. Although she grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, she and her sister returned to Knoxville each summer to visit their grandparents. Nikki graduated with honors in history from her grandfather’s alma mater, Fisk University. Since 1987, she has been on the faculty at Virginia Tech, where she is a University Distinguished Professor.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.