Privilege, Pageantry, and PR

Carrie Tipton traces the complex origins of college fight songs

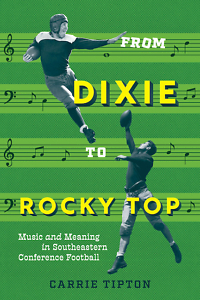

If you follow Southeastern Conference football (and perhaps even if you don’t), you’ve most likely got an SEC fight song or two permanently lodged in your brain. Anthems like Auburn’s “War Eagle” and Louisiana State University’s “Fight for LSU” are an indelible part of college football culture, and popular tunes — “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Rocky Top” — are enlisted to rev up the crowds as well. In her book From Dixie to Rocky Top, Carrie Tipton reveals a surprisingly complex history behind this music, a history that encompasses class, race, gender, and our evolving regional identity.

Tipton, who studies the intersection of music, religion, history, and culture, currently teaches at Vanderbilt University. She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Tipton, who studies the intersection of music, religion, history, and culture, currently teaches at Vanderbilt University. She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: I suspect most of us think of college songs as something akin to folk music, but you analyze them as “commodities, shaped by market forces, that exist as copyrighted entities within the U.S. music industry.” Why did you choose that avenue to explore this history?

Carrie Tipton: Short answer: This is where the primary sources took me. When I started to pull on the threads of where these songs “came from,” I ran across lots of evidence of a vibrant college song sector in U.S. commercial music from roughly the early 20th century until World War II. Although we now associate college songs or fight songs with marching bands, they were once part of mainstream popular music, circulating well beyond campus and marketed by niche publishers who fought legal battles to protect their copyrights (and thus, royalties). Stars like Rudy Vallée and Fred Waring performed and recorded college songs; dance bands played them in “hot” arrangements at social events; records and especially sheet music and songbooks of them were for sale at music stores.

I try to show in the book that these musical phenomena were part of a broader U.S. pop culture fascination with (white) college life that peaked between the world wars and included college-themed musicals, movies, novels, plays, and visual advertising. When you hear college songs today, you are often hearing a vestige of the U.S. love affair with the mystique surrounding college life before World War II and which, commodified by the popular culture industry, helped musically define a new kind of youth culture prior to the advent of rock and roll in the 1950s.

Chapter 16: You point out that early Southern football pageantry was rooted in social hierarchy. The privilege of white male elites to act out, to engage in the public revelry of “nightshirt parades” and such, wasn’t shared by other groups. Did people see these activities at the time as a way of forging identity around class?

Tipton: Here I was building on the work of historian Andrew Doyle, who first made this point, and fleshing it out sonically and musically. To answer your question, let’s think about three categories of historical actors. First, I didn’t come across any evidence that participants thought of their pageantry as an engine to create or solidify class identity. The forging of U.S. class identity is often silent or unmarked in its own time, more discernible to those of us doing retrospective analysis than to those doing the forging. More particularly, these participants generated lots of print sources (cheers, yells, songs, poems, descriptions of revelry), but those do not contain much self-reflection on this or other matters.

Tipton: Here I was building on the work of historian Andrew Doyle, who first made this point, and fleshing it out sonically and musically. To answer your question, let’s think about three categories of historical actors. First, I didn’t come across any evidence that participants thought of their pageantry as an engine to create or solidify class identity. The forging of U.S. class identity is often silent or unmarked in its own time, more discernible to those of us doing retrospective analysis than to those doing the forging. More particularly, these participants generated lots of print sources (cheers, yells, songs, poems, descriptions of revelry), but those do not contain much self-reflection on this or other matters.

Second, in terms of observers who may have had critical distance to consider the racialized and gendered class-identity potentialities of football pageantry (working-class white Southerners, Black Southerners, women of any station), their voices are vastly underrepresented in extant print sources. We really don’t know what they thought about it because the people creating and preserving the relevant sources mostly fell into the first or third categories here.

Third, in terms of observers who sanctioned and welcomed this wild pageantry (i.e., Southern newspapers of record), they celebrated the behaviors largely for reasons of civic boosterism and weren’t too concerned with parsing the social dimensions of rowdy (in some cases, as the book shows, illegal) collegiate conduct.

Chapter 16: You devote a chapter to Huey Long’s enthusiastic “micromanagement” of LSU’s marching band in the 1930s, when he was Louisiana’s governor and then senator, even though he never attended the school. How did Long’s association with LSU intersect with his populist politics?

Tipton: The book doesn’t really address this because I don’t think his LSU association had much to do with his populism; I think there are better historical explanations for it. At times (such as in his speculative fiction book My First Days in the White House) Long gestured vaguely at the idea of “college for all,” but from what I’ve picked up in Louisiana political historiography and primary sources, his populism wasn’t always fleshed out in a robust agenda, so it’s tough to link his LSU activities to any specific policy.

Instead, his very visible role in LSU football pageantry reflected more of a generic Louisiana boosterism. In interviews, Long defended LSU’s costly state-funded trips to away games as a valuable form of advertising for the school and the state. This stance, not unique to him, reflected a belief developing across SEC territory and institutions in the 1930s that a flagship school could generate good PR and therefore money for its host state. Also, as the book shows, his LSU activities stemmed partly from a personal infatuation with the mystique of collegiate life. This trope or obsession also wasn’t unique to him: It saturated 1930s U.S. popular culture. And it wasn’t a very populist trope; it valorized a (whitewashed, male-dominated) middle- and upper-class vision of college life. For me, these were more compelling, coherent explanations for his LSU activities than trying to root them in his populist ideology.

Chapter 16: Alumni seem to have played a major role in the evolution of these songs. One example you give is textile magnate Roy Sewell, who made Auburn boosterism “a form of civil religion” in the 1950s. Why do you think so many people retain such passionate interest in college football pageantry long after their college days are over?

Tipton: Scholars talk a lot about how contemporary sports fandom provides a sense of belonging, collective identity, and rootedness that can be hard to come by in globalized modern societies. This might be doubly true of fandom rooted in the U.S. college experience (think about the term “homecoming”).

College is an intense, unique social experience that imprints heavily on the memory at a formative developmental stage. When the sensory and embodied elements of college football, experienced collectively, figure into that experience, they create strong emotional ties for participants, to each other, and to formative places, spaces, and rituals. On top of that, many SEC alumni were raised in the southeastern U.S., often within fandoms of a specific SEC school, so they experience aspects of that emotional imprint long before they ever attend university. The book also briefly riffs on the idea that the seasonal rhythm of college football — all the more elemental for its brevity — functions like a liturgical calendar for some people, providing a sense of shape and order to their year.

Chapter 16: “Rocky Top,” or as you call it, “UT’s institutional earworm,” didn’t go over that well when it was introduced at games in the 1970s, and people even complained that it was played too much. What does it say about Southern football culture that the song has now become an “ironic avatar” for the team and the university?

Tipton: Since UT started using “Rocky Top,” the song has come to convey a very powerful imagined idea of place, which as the book shows has been a musical through-line in SEC football culture. The song’s reception history in the region, tied to its association with UT, also highlights the symbolic and even material power of popular culture. There was no actual Rocky Top until the town of Lake City, Tennessee, won a legal battle in 2014 against the song’s copyright owners to change the town’s name to the song title.

The newly baptized town of Rocky Top is a little north of Knoxville. It’s safe to say that UT’s embrace of “Rocky Top” encouraged this kind of multifaceted regional commodification of the song’s Appalachian imaginary. It is much more than a fight song: It is an outsized example of how football rituals and traditions can mushroom beyond relatively simple origins to become anchors of institutional, fan, and civic identity, although that is certainly not unique to the South. Also, more broadly, UT’s embrace of the song — which saturates the school’s iconography, sonic identity, physical plant, and licensed merchandise — highlights the importance of branding and marketing in modern higher education.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.