Prophets of Doom

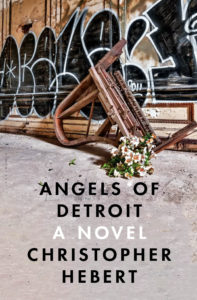

In Christopher Hebert’s Angels of Detroit, young idealists believe they must destroy the city to save it

Christopher Hebert’s new novel, Angels of Detroit, features a cast of characters who believe the apocalypse is coming, and the mass of humanity is too narcotized or distracted to pay attention. “The planet [is] heating, ice caps melting, species dying, ecosystems collapsing,” one character thinks. “The sixth extinction would wipe out everything now living, changing the world forever.” Hebert’s doomsayers, drawn from diverse generations and socio-economic backgrounds, share two characteristics: they don’t appear overly sad about the prospect of annihilation, and they live in Detroit.

Angels of Detroit paints its urban setting as a crumbled wasteland. Burned-out buildings, razed factories, and boarded-up houses appear in every vista. Grand streets still featuring Gothic churches and art-deco offices are now so empty they can’t sustain a decent criminal element. One newcomer to Detroit finds the “city grid intact, but the city itself had disappeared. Empty.” For readers unfamiliar with the five-decade decline of the Motor City, Hebert—a Knoxville novelist who earned an M.F.A. from the University of Michigan—offers demographic facts and visual aids: “a city of one hundred forty square miles, a third of it abandoned, the emptiness combined larger than the entire city of San Francisco. Boston. Manhattan. Almost two million inhabitants at the city’s height. Two-thirds of them now departed.” What better place to envision the end times than a beleaguered metropolis that seems to have suffered the cataclysm already?

Angels of Detroit paints its urban setting as a crumbled wasteland. Burned-out buildings, razed factories, and boarded-up houses appear in every vista. Grand streets still featuring Gothic churches and art-deco offices are now so empty they can’t sustain a decent criminal element. One newcomer to Detroit finds the “city grid intact, but the city itself had disappeared. Empty.” For readers unfamiliar with the five-decade decline of the Motor City, Hebert—a Knoxville novelist who earned an M.F.A. from the University of Michigan—offers demographic facts and visual aids: “a city of one hundred forty square miles, a third of it abandoned, the emptiness combined larger than the entire city of San Francisco. Boston. Manhattan. Almost two million inhabitants at the city’s height. Two-thirds of them now departed.” What better place to envision the end times than a beleaguered metropolis that seems to have suffered the cataclysm already?

Hebert takes his time in weaving together the various narrative strands, making connections that seem merely coincidental at first but deepen as the chapters progress. McGee, an idealist who believes corporate sabotage is justified, makes a peculiar alliance with Darius, a night-watch security guard with anti-capitalist schemes of his own. Their target, the fictional HSI corporation, plans to shut down its last local factory, though it is getting pushback from executive Ruth Freeman, a Detroit native suffering twinges of conscience. Another story line follows the travails of a young prophet, Dobbs, whose quasi-religious pilgrimage to Mexico runs way off track. Indebted to the leader of an underground cartel, Dobbs is sent to Detroit to set up advance operations for a large-scale criminal undertaking, the outlines of which come slowly into focus.

The characters alternate in the central frame, but Hebert’s concentration remains on the city itself. In this novel, Detroit is emblematic of the coming annihilation, its collapse a model for imminent world-wide catastrophe. William Gibson has said that the future is already here; it’s just not evenly distributed. Angels of Detroit represents a dramatization of that truth. The future that has arrived is not globalization of markets, communication, and affluence, but widespread degradation, desperation, and revolution. The planet itself, according to Dobbs, is joining the revolt. “Drought throughout the West. Hurricanes from the Gulf to the Atlantic. These were just teasers,” he thinks. “But people denied what they were too scared to face.” In this context, Detroit’s downfall is a portrait of the world to come.

Hebert’s dyspeptic narrator makes mouths at Pollyannas who envisage Detroit’s recovery. Urban renewal gets mentioned only as outmoded pipe dreaming. “Every couple of months it was something new, some grand plan to bring the city back from the brink,” Darius thinks. “Artists were going to save it, filling empty warehouses with ceramics and easels. Or urban hipsters would come, spawning microbreweries and coffee shops. Or all the empty factories would be converted to make solar panels.” Residents no longer hope for salvation; they know that the disease has taken root. In a typically run-down neighborhood, Dobbs observes “a pair of water towers, dipped in rust. … The factory underneath looked as though it were being consumed from within by some sort of cancer.”

Hebert’s dyspeptic narrator makes mouths at Pollyannas who envisage Detroit’s recovery. Urban renewal gets mentioned only as outmoded pipe dreaming. “Every couple of months it was something new, some grand plan to bring the city back from the brink,” Darius thinks. “Artists were going to save it, filling empty warehouses with ceramics and easels. Or urban hipsters would come, spawning microbreweries and coffee shops. Or all the empty factories would be converted to make solar panels.” Residents no longer hope for salvation; they know that the disease has taken root. In a typically run-down neighborhood, Dobbs observes “a pair of water towers, dipped in rust. … The factory underneath looked as though it were being consumed from within by some sort of cancer.”

This heavy theme could have become a slog, but Hebert elevates the mood through comic characterizations. McGee’s small faction, which includes her boyfriend and a handful of friends, provides humorous reminders that, even on the brink of Armageddon, young people will drink too much, make dubious sexual choices, and define themselves by consumerism. Hebert exposes the squalor of McGee’s and Myles’s living conditions as so much pretentious penury. They live in a jury-rigged warehouse in substandard conditions simply to nurse their political grievances. “McGee and Myles could have bought a whole house with the change in [their friend’s] ashtray, but they enjoyed living like this. Or they wanted to enjoy living like this,” Hebert writes. “Sometimes it was hard to tell the difference.”

The novel maintains a balance of comedy and drama, juxtaposing cockamamie plans for infiltrating a corporate headquarters with the very real dangers that Dobbs faces. Despite the novel’s dark outlook, Hebert drops in wisecracks that push the needle away from the tragic and toward the absurd. When at fourteen Dobbs announced that he was giving up “pork chops and fish caught with anything other than a pole,” his parents, both professors, trust he has a future in ecology: “It was as if they believed that the world couldn’t be extinguished as long as there was graduate school.”

The title takes on different meanings over the course of the novel. Are the angels benevolent or sinister? Is their mission to care for the living or to transport the dead? Angels of Detroit, though ineffective as a travel brochure, pays homage to a city that at one time embodied the country’s image of homegrown success, built with a uniquely American combination of brains and brawn. Whether the angels will save it from destruction or accelerate its tragic fate, the broader question this novel asks is whether the rest of the U.S. is fated to follow its path.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.