Prowling Like Maggie the Cat

In a posthumous collection, poet Diann Blakely casts her lot with outsiders

The late Nashville poet Diann Blakely died in 2014 of a chronic lung disorder, a few years short of her sixtieth birthday. A lifelong rebel and pioneer, Blakely carved out for herself a niche only she was equipped to occupy. Her disappearance from the literary scene at a moment when she should have had a couple of decades of productive time to look forward to is tragic. The loss to Southern letters of this passionate and daring poet is immense.

Blakely was an Alabama native, a daughter of the traditional South who challenged her heritage in powerful ways. Significantly, she was one of the first female students at the University of the South at Sewanee, home to The Sewanee Review and previously an all-male bastion not only of maleness but also of Southern gentility. Sewanee’s literary values at the time had their roots in the Confederacy—the university was the proud bailiwick of Fugitives and Agrarians such as Allen Tate and Andrew Lytle.

Blakely was an Alabama native, a daughter of the traditional South who challenged her heritage in powerful ways. Significantly, she was one of the first female students at the University of the South at Sewanee, home to The Sewanee Review and previously an all-male bastion not only of maleness but also of Southern gentility. Sewanee’s literary values at the time had their roots in the Confederacy—the university was the proud bailiwick of Fugitives and Agrarians such as Allen Tate and Andrew Lytle.

Though many welcomed the admission of women, there was also a hostile backlash, and Blakely was alert to that dynamic. As it happens, I am also a Sewanee graduate—class of ’62 while she was class of ’79—and was one of her teachers at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont. In later years she always insisted that I had said to her, “Don’t be such a lady in your writing.” I don’t recall giving that advice, but if I did it’s ironic because a central dynamic of her work is her relentless questioning of the lady-and-gentleman culture many of us were brought up to respect and adhere to. It’s hard to imagine a time when anyone could have seen Diann Blakely as an exemplar of Southern gentility.

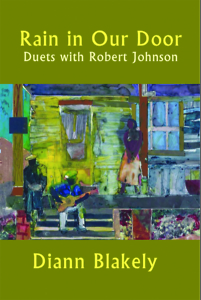

Rain in Our Door: Duets with Robert Johnson is Blakely’s last and most radical book. The title is taken from what are perhaps the best known of the Mississippi musician’s lyrics: “You better come on in my kitchen, cause there’s gonna be rain in our door.”

“Our” is a significant word in Blakely’s title. An outsider in the world of white-male privilege in which she grew up, Blakely identifies in these poems with other outsiders—and not only Robert Johnson, greatest of the Delta bluesmen, who emerged from the oppression and poverty of the plantation South, where sharecropping for starvation wages was not far removed from slavery itself. She also identifies with Tennessee Williams, another rebel whose difference was sexual rather than racial. She empathizes with Maggie in Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: “I’ll night-prowl like Maggie the Cat / From porch to bedroom, with my red fingernails / Arched prayerfully inside soon-peeled white gloves. … O I’ll undress / Down to my humid white-girl slip, like Cat, / And we’ll yowl….”

For readers who don’t happen to be hardcore blues fans, the poems in the book are buttressed by impressive explanatory notes. “The Life” provides a succinct biography of Robert Johnson; “The Afterlife” traces his journey from obscure, scuffling performer in Delta juke joints, plantation house parties, and migrant worker camps to the blues icon that he has posthumously become. The thirteen-page section modestly called “Notes” actually constitutes a cogent and informative essay on racial oppression and the way Johnson figures into the larger post-slavery story of the Deep South.

For readers who don’t happen to be hardcore blues fans, the poems in the book are buttressed by impressive explanatory notes. “The Life” provides a succinct biography of Robert Johnson; “The Afterlife” traces his journey from obscure, scuffling performer in Delta juke joints, plantation house parties, and migrant worker camps to the blues icon that he has posthumously become. The thirteen-page section modestly called “Notes” actually constitutes a cogent and informative essay on racial oppression and the way Johnson figures into the larger post-slavery story of the Deep South.

Using Johnson’s song “Stones in My Passway” as the title and springboard for a poem with the same title, Blakely renders one of the most powerful and sickeningly well-imagined descriptions of the horror of the Middle Passage’s slave ships I have ever read:

Imagine four months’ worth of vomitus and sweat,

Piss, blood, hard starveling feces

Clotted on chain-mangled skin; the moans, and curses spat

At gods whose heads turn from these seas;

Imagine buckets of stale water slapped on your flesh,

Its sores disguised with tar, as you

Step toward the auction block….

Black and white, Anglo and African-American—we Southerners have been part of one another’s lives for centuries. In some obvious ways we remain two separate peoples, yet at the same time our common experiences and temperaments sometimes hint at the existence of a shared and unified culture. If this synthesis ever does finally come into being, fearless voices like Diann Blakely’s from both sides of the racial divide are going to be absolutely essential.

Richard Tillinghast is a Memphis native whose most recent book is Journeys into the Mind of the World: A Book of Places, University of Tennessee Press, 2017.