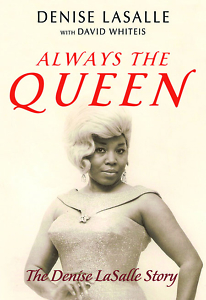

Queen’s Rules

Late R&B legend Denise LaSalle always called her own shots

In her posthumous memoir, Always the Queen, the fiercely unapologetic Denise LaSalle looks back at her illustrious career as a self-made R&B icon. Co-written with blues historian David Whiteis, the narrative is told from LaSalle’s perspective and draws largely from transcripts of conversations between the two collaborators and friends.

In 1963, a young LaSalle signed her first recording contract with Chess Records — the pre-eminent blues label that launched legends like Muddy Waters and Etta James. But the magic faded for the singer and songwriter shortly after she signed. The label wouldn’t record her material, and she had her suspicions as to why. “See, I wouldn’t go there [the studio] alone,” she writes. In those days, manipulative tactics from male power brokers were, depressingly, a music industry standard. Yet LaSalle kept her guard up around label execs, despite the effects this may have had on her early career: “I honestly think I could have recorded … had I been the kind that they could take advantage of.”

A year later, LaSalle wrote to Chess saying she wanted out of her contract. The label said they’d cut her record in the next two weeks. Unconvinced, she dropped them and moved on.

LaSalle’s refusal to cede to the power structures that try to control her is a delightful theme throughout Always the Queen. She sets the rules in the early pages: “I never let anybody rule me. I’ve always been my own woman. I always had the contracts written where I could call my own shots. And if they didn’t like it, they didn’t get me.”

These principles were ingrained in her at a young age. Born in 1939, LaSalle grew up belting gospel and country tunes while picking cotton in Mississippi with her parents, who worked as sharecroppers. She looks back fondly on life in the country, but her family’s move to Belzoni when she was 13 woke her up to the hostile realities of the racist Jim Crow-era South. Nicknamed “Bloody Belzoni,” the town was the site of the 1955 murder of Rev. George Lee, a Black minister who advocated for African American voting rights throughout the Mississippi Delta. The police tried to cover up his murder as a traffic accident, and the case was never solved.

The trauma of Rev. Lee’s death and the widespread racial violence she witnessed in Belzoni angered LaSalle but also mobilized her. Staying in Mississippi, she explains, didn’t offer prospects for independence or stardom, the only life she imagined for herself: “I knew I couldn’t take what a lot of people took. I would have to be sassy and fight back. Probably end up getting killed. So, I just said, ‘I want out. I can’t stay in this part of the country, or I will be dead.’”

She forged her own path by moving to Chicago. Cutting her teeth in the South Side nightclub circuit, she transformed from barmaid to bona fide diva in a few years. Shortly after the Chess incident, she landed another recording contract and cut her first album, A Love Reputation, released in 1967. She then moved to Memphis in the early 70s, where she recorded “Trapped by a Thing Called Love,” her career-defining hit that solidified her eternal place in the blues canon.

Always the Queen is LaSalle’s victory lap, a catalogue of her successes and memorable moments in a 50-year career of recording and touring. From playing with Lou Rawls in Sweden to cooking dinner for Bill Withers, LaSalle revels in the memories of friends and collaborators, describing those who touched her life in full and loving detail. She also dishes out unfiltered anecdotes about run-ins with Ike Turner, Aretha Franklin, and even Bob Dylan.

Always the Queen is LaSalle’s victory lap, a catalogue of her successes and memorable moments in a 50-year career of recording and touring. From playing with Lou Rawls in Sweden to cooking dinner for Bill Withers, LaSalle revels in the memories of friends and collaborators, describing those who touched her life in full and loving detail. She also dishes out unfiltered anecdotes about run-ins with Ike Turner, Aretha Franklin, and even Bob Dylan.

At times in Always the Queen, the singer comes off as self-congratulatory, even cocky. But why shouldn’t she? Self-possessed and fearless, LaSalle created herself in her own image, managing a roster of businesses — including record labels, radio stations, and a wig shop — and controlling her musical output. “You see my name listed as producer on most of my records, and that’s exactly what I am,” she writes. A pioneer for female R&B entertainers at the helm of their own enterprises, LaSalle clearly earns every right to be the unrepentant diva that she is.

While LaSalle may have left mooching ex-boyfriends and thankless record labels, she never strayed from the music. In 2009, she was crowned the “Undisputed Queen of the Blues.” Her last years were spent performing at blues festivals and advocating for the genre’s preservation. LaSalle and her husband, James Wolfe, a legendary figure in West Tennessee radio, settled down together in Jackson in the late 70s and called the city home for 40 years. The final chapters depict LaSalle as buoyant and still dreaming. After her leg amputation due to a fall in 2017, “the one-legged diva,” as she called herself, was aching to start a blues academy. “By teaching these kids the blues,” LaSalle writes, “and by teaching them the history of the blues, we’re teaching them the history of their own people.”

LaSalle passed away in 2018 and never had the chance to start the academy. Yet Always the Queen serves as an entertaining and boldly rendered look into the history of the classic genre that LaSalle loved and honored with her life.

Jacqueline Zeisloft is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in the Nashville Scene and the Women’s Review of Books. She holds a B.A. in English literature from Belmont University and is a graduate of the Columbia Publishing Course. She currently resides in Brooklyn, New York.