Race and Justice in Reconstruction-Era New Orleans

Michael A. Ross recovers the fascinating story of a forgotten kidnapping case that reveals the complexities of Reconstruction-era politics

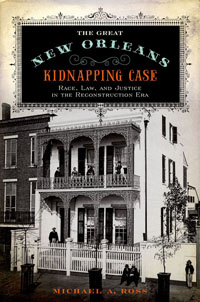

In The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case, historian Michael Ross adapts the genres of true-crime narrative and courtroom drama to recover a forgotten story that captured national attention nearly 150 years ago. In clear, bright prose illuminated by meticulous archival research, Ross deftly sorts through the complexities of Reconstruction-era politics to tell the story of two mixed-race women accused of abducting a white toddler.

Molly Digby, the seventeen-month-old daughter of a working-class Irish family in New Orleans, was allegedly taken in 1870. The historical setting is critical. As Ross notes, the case turned “an unlikely group of previously little known individuals—a working class Irish family who lived in the ‘back of town,’ a cigar-maker turned detective, and two beautiful, stylish, and publicity shy defendants—into significant actors in the unfolding drama of Reconstruction.”

The politics of that “unfolding drama” complicated the case in important ways. Louisiana was then under the governorship of Henry Clay Warmoth, a twenty-eight-year-old moderate Republican. Given its unique history, New Orleans served as a testing ground for the democratic vision of post-War Republicans. With its highly educated Afro-Creole elite (a vestige of French rule), New Orleans seemed especially suited to the interracial sharing of power.

The politics of that “unfolding drama” complicated the case in important ways. Louisiana was then under the governorship of Henry Clay Warmoth, a twenty-eight-year-old moderate Republican. Given its unique history, New Orleans served as a testing ground for the democratic vision of post-War Republicans. With its highly educated Afro-Creole elite (a vestige of French rule), New Orleans seemed especially suited to the interracial sharing of power.

At the same time, the case threatened to ignite an already heated racial climate—both in the city and beyond—because of its major players: a white baby allegedly taken at the hands of Afro-Creole kidnappers. By finding and then successfully prosecuting these women, the Republican administration hoped to stave off widespread accusations of incompetence and corruption levied by their Democratic opponents, thereby proving the professionalism of its interracial police force. Initially the lead detective on the case was John Baptiste Jourdain, a man characterized as “intelligent and well educated”—and also “slightly colored.” In a tremendous historical irony, an Afro-Creole detective would have to prove his fitness by prosecuting two of his own community. The case would only grow more complicated as it moved to its ambiguous conclusion.

Because of the rigid racial boundaries drawn after Reconstruction under Jim Crow, the peculiar context for this case invites speculation about what might have been: the Digby case, Ross writes, could “help explain both how Reconstruction might have succeeded and why it failed.” In effect, Ross plays a game of double-detection: The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case is a story of detectives and their work wrapped up in a contemplation of the historian’s craft as a kind of detective work.

Throughout the book, Ross works through the larger political meaning of the case, considering matters of historical contingency, particularly the way things would change in the aftermath of Reconstruction and the coming of white-racist “redemption.” At a more intimate level, he carefully measures possible answers to the remaining mysteries of the case itself—the product of rumor, literary invention, or family lore—and always sides with the extant historical records. (The story of how Ross found the story and pursued it makes his “Afterword and Acknowledgments” among the more interesting I’ve read in years.)

Throughout the book, Ross works through the larger political meaning of the case, considering matters of historical contingency, particularly the way things would change in the aftermath of Reconstruction and the coming of white-racist “redemption.” At a more intimate level, he carefully measures possible answers to the remaining mysteries of the case itself—the product of rumor, literary invention, or family lore—and always sides with the extant historical records. (The story of how Ross found the story and pursued it makes his “Afterword and Acknowledgments” among the more interesting I’ve read in years.)

Throughout, he manages to blur genres in productive ways. The text follows a tried-and-true formula for crime fiction, as Ross sets up the dramatis personae, delving into their backgrounds before telling the story of the crime and then the trial. He concludes by tracking the major players’ stories to their respective vanishing points in the historical record. The broad middle of the book adds up to a courtroom drama, with a detailed account of legal proceedings and exchanges taken from various witnesses to the case.

For readers interested in cultural matters, The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case includes a richly textured portrait of nineteenth-century life, from prevailing attitudes about crime and criminality to Victorian gender sensibilities—all complicated by racial considerations. The colorful lives of some of these historical figures tell us a great deal about the fluidity of a newly urbanizing, industrializing nineteenth-century American society, full of upwardly (and downwardly) mobile people on the make, some of them doomed to horrible fates because of racism, others assimilating into mainstream society or middle-class respectability, and still others showing a capacity for duplicity in the style of Melvillian confidence men.

This description does only partial justice to a case and a time knotted with political, racial, and cultural complexities. That Ross manages to draw the reader into the story while patiently unraveling these complexities testifies to his immense skill as a narrative historian. The story of Reconstruction can be daunting for its level of political and racial intricacy; Ross delivers a compelling, even intimate story that deals intelligently with broad regional and national political matters at the same time. Few if any historical treatments of Reconstruction have achieved the same measure of analytical clarity in such an attractive and compelling package.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and writes scholarly articles about the civil-rights movement and different features of American thought.