Race, Rights, and Reconstruction

Daniel Brook chronicles the shifting status of mixed-race elites in the 19th-century South

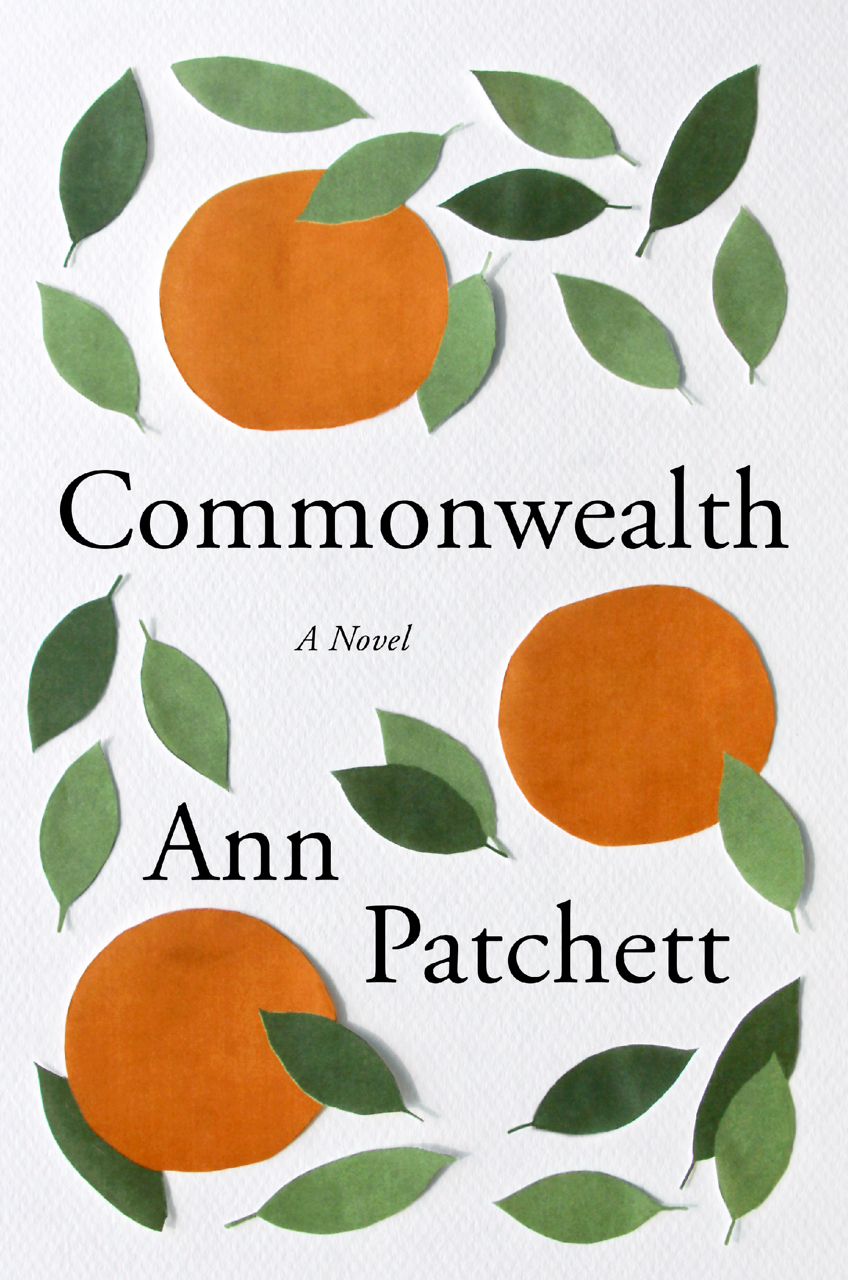

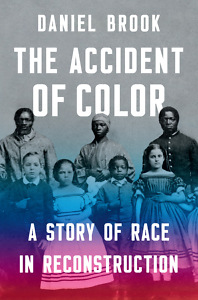

In 19th-century Charleston and New Orleans, mixed-race elites flourished. Daniel Brook’s The Accident of Color relates their saga, explaining their complicated place in society, their civil rights activism, and their ultimate subjugation under the racist regime of Jim Crow.

Brook’s previous book, A History of Future Cities, was selected as one of the “Top Ten Favorite Books of 2013” by The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, and The Nation. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: By telling the story of the Creoles of New Orleans and the Browns of Charleston, you make an argument about race itself. What is “race,” anyway?

Daniel Brook: The histories of New Orleans’ “Creoles of color” and Charleston’s “Browns” invite us to think about “race” in a new way. Their conception of race was that in the New World, people from all continents live jumbled together and, invariably, they mix together. These mixtures are always a matter of addition, not subtraction, so each generation is more mixed than the last. While this idea sounds odd to us, it’s long been accepted in societies in Latin America, such as Brazil and Colombia, that had slavery but never Jim Crow. The New Orleans Creoles and Charleston Browns keep needling American society, arguing that they’re not the only mixed Americans; they’re just the only Americans who aren’t covering it up. Today, as more Americans uncover their mixed roots through genetic genealogy, they’re finally being proven right. European heritage is nearly universal among African Americans, and millions of self-described “white” Americans are now learning that they are of partial African descent.

Chapter 16: What is special about New Orleans and Charleston? Why does a mixed-race class flourish within each city?

Brook: New Orleans is a very special case. It is founded as a French colony in 1718 and then becomes a Spanish colony, then French again, and only becomes part of the U.S. in 1803. Naturally, it uses the Latin American racial system because it’s a Latin American city before it’s an American city.

Charleston is slightly harder to explain. Historically, South Carolina was more closely linked to the Caribbean than the other 13 colonies. Fully six of its colonial governors between 1670 and 1730 were immigrants from Barbados, not England. And like many Caribbean islands, but unlike most American settlements, it had a slave majority. This makes the master class very nervous and eager to make free mixed-race people their allies rather than their enemies. As in the Caribbean, free mixed-race people become a middle-class buffer between the slaveowners and the enslaved. As white indentured servitude declines and racism becomes more and more the main justification for the institution of slavery, these mixed-race free people become increasingly anomalous and seen as suspect by the wider American society.

Chapter 16: How does the status of the Creoles and Browns evolve during the Civil War and into Reconstruction? Why?

Brook: A few years before the Civil War, the Supreme Court rules in the Dred Scott case that Americans of African descent are no longer citizens of the United States. This is a devastating ruling for free people of color. Upon secession, the communities in New Orleans and Charleston initially cozy up to their white Confederate relatives but soon break ranks and start fighting for the Union. With emancipation and universal male suffrage, all of a sudden majority-nonwhite states such as Louisiana and South Carolina become the most likely candidates to enforce equal rights. Mixed-race community leaders take the lead in fighting for them.

In the backlash against Reconstruction, the dispossessed white elite embraces a strategy to rebuild a slave economy without slavery; they replace a society based on a distinction between slave and free with a society divided between black and white. The threat to freeborn people of color now becomes even starker and they fight the hardest to stop the nascent system. They take multiple civil rights cases all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in the late 19th century, of which Plessy v. Ferguson is only the last and most famous.

Chapter 16: Could these leaders craft a civil rights agenda during Reconstruction? What were their successes and failures?

Chapter 16: Could these leaders craft a civil rights agenda during Reconstruction? What were their successes and failures?

Brook: It’s stunning to see how closely the demands and accomplishments of the 1860s civil rights activists line up with those of the better-known 1960s activists: school desegregation, open seating on public transit, service at lunch counters. At the height of Reconstruction, the federal government recognized virtually all of the rights that were subsequently trampled under Jim Crow. But enforcement was always an issue. New Orleans and Charleston — with their educated, wealthy, non-white populations, their healthy doses of immigrants from the North and from Europe, and their integrated police forces — went much further in making these rights a lived reality than most other places. In much of the South, equal rights existed on paper only.

Chapter 16: Homer Plessy, the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, was an “octoroon” from New Orleans. How did the old mixed-race class stand at the center of debates over Jim Crow laws in the 1890s?

Brook: The nuts-and-bolts answer is that mixed-race New Orleans Creoles of color were at the forefront of fighting for civil rights because they were wealthy and educated in a time when most African Americans had been born in chains, subjected to state-enforced illiteracy, and freed without backpay. There’s no NAACP Legal Defense Fund or ACLU in this period that takes in donations and represents you for free if you think you’ve been discriminated against, so if you want to take a test case to the Supreme Court, you and your allies need to pay a lawyer to do it for you.

But it’s not only these practical reasons. The trial transcripts from the civil rights cases make clear that they were also at the center of fighting Jim Crow laws because they know intellectually — and feel personally — that the notion that Americans could be divided into binary categories of “white” and “colored” is fallacious. Homer Plessy, with his mixed background, was legally a “white man” in some states and a “colored man” in others because the states’ racial definitions never matched up. Because we grew up in a racist society, these Jim Crow notions that Americans can be “white people” or “POCs” seem normal to us. But they didn’t seem normal when they were first invented. Mixed-race people were at the forefront of challenging them because their own backgrounds so clearly didn’t fit this binary scheme.

Chapter 16: In the preface to The Accident of Color, you discuss the white-supremacist “Dunning School,” which shaped popular understanding of Reconstruction for much of the twentieth century. In the concluding bibliographic note, you call W.E.B. Dubois’s Black Reconstruction and Eric Foner’s Reconstruction the “Old and New Testaments” of modern scholarship on this period. How have historical interpretations evolved? What are the stakes?

Brook: The victors write the history and, tragically, in the late-19th century, the bad guys won. The “Dunning School” that first wrote this history viewed the granting of civil rights during Reconstruction as, at best, a naïve mistake and the Klan terrorism that overturned it as, at worst, a necessary evil. Part of the sleight of hand in this interpretation is to fully conflate blackness with slavery and allow less-informed readers of their history books (and viewers of the movies they inspired) to believe that African American legislators in places like South Carolina and Louisiana had been illiterate field hands before the Civil War. In truth, the legislative leaders in these states were typically free-born people, many of whom, because of American racism, had been forced to seek higher education in Europe in an era when European universities were superior to American colleges. Many in this group were better educated than their white counterparts.

Starting with W.E.B. DuBois in the 1930s, then with more historians in the 1960s and 70s, and finally with Eric Foner’s comprehensive reinterpretation of Reconstruction in 1990, the “Dunning School” was discredited. But I feel that even this new revisionist work has not thoroughly reckoned with the fact that our current notions of “white” and “colored” come out of this period but did not exist going into it. Our nation’s continuing struggles with racism, despite the dismantling of Jim Crow, are intertwined with that.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.