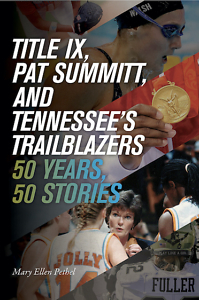

Raise the Roof for Tennessee Women and Title IX

Mary Ellen Pethel celebrates the lives of 50 Tennessee women athletes

Historian Mary Ellen Pethel’s latest project combines her twin passions for history and sports. In Title IX, Pat Summitt, and Tennessee’s Trailblazers, Pethel measures the impact of 50 years of Title IX legislation on Tennessee women’s athletics in higher education. By telling the stories of 50 Tennessee women, she makes a compelling case for the critical role they played in making the public policy meaningful and transforming the state’s image nationwide in the process.

Pethel, assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies and global education at Belmont University, is the author of several books, most notably Athens of the New South: College Life and the Making of Modern Nashville. She is also the creative mind behind NashvilleSites.org, a digital project focused on self-guided, mobile-friendly walking tours in Nashville. She can be found on Instagram and Twitter.

Pethel, assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies and global education at Belmont University, is the author of several books, most notably Athens of the New South: College Life and the Making of Modern Nashville. She is also the creative mind behind NashvilleSites.org, a digital project focused on self-guided, mobile-friendly walking tours in Nashville. She can be found on Instagram and Twitter.

Mary Ellen Pethel answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: Could you say a few words about how you decided on the unique form this book ultimately took on, namely its stories and its various vignettes?

Mary Ellen Pethel: I was sitting in a coffee shop in March 2020, not knowing that the COVID-19 pandemic would soon shut down most of the world. A friend had sent me a link to a newspaper article about the first full-court women’s high school basketball game in the modern era here in Tennessee. It was much later than you might imagine — not until 1979 — seven years after the passage of Title IX. Granted, women’s college programs in Tennessee had been playing full court since the late 1960s, but that article piqued my interest, to say the least.

I researched further and reached out to an editor at the University of Tennessee Press with whom I’d worked before and pitched an idea for a book about Tennessee women and athletics in the Title IX era. I asked, “What about a book with short chapters or case studies that — taken together — would tell the collective story of modern women’s sport in the state?” This seemed a way to write for a larger audience and in a conversational tone, without sacrificing the scholarly source-work necessary for a project of that scope. My book proposal was approved, and I set about my work.

Oral history was critical to the project from the start. I began interviewing people I knew and envisioned interviewing 15 or 20 people to feature in the book. Of course, I knew Pat Summitt would figure centrally. She was obviously at the center of the Title IX era in Tennessee. There was rich source material for Pat, even though she had passed away in 2016, including three books she wrote and countless articles and interviews. I also interviewed friends and former colleagues and players who added to her life story, which I split into three chapters. Each chapter about Pat Summitt begins a new section in the book.

From there it evolved into something much more than I could have anticipated. The people on my initial list consistently referred me to more women I should interview. A common refrain was: “Well, I’m so glad to talk to you, and I’m happy to tell you my story, but have you reached out to so-and-so?” Or, “You really need to include this person or that person.” It grew organically from there, and a fuller, richer picture began to take shape.

I also learned, once I scratched the surface with some of the bigger names — some of the early prominent figures, the ones who have been well documented — that everyone knows everyone. It’s a surprisingly tight network of women, administrators, coaches, and even early athletes. These women were often fierce competitors on the field of play, but they all worked together to advance the women’s game. Many of these women were unsung heroes in the late 1960s, 70s, and into the 80s. Their stories need telling, just as much if not more than the best known figures, because many of these women never received the credit they richly deserved during their professional careers.

Once I got to 40 stories, I realized that I wanted to get to 50. You mentioned the vignettes. I made that choice, with consultation and guidance from my editor, as the sources came together. There were around 15 women whose stories were important to women’s sports and to women in higher education more broadly in Tennessee, but there wasn’t enough source material to create a featured chapter. Yet, their experiences needed to be included to tell the full story. That’s how we landed on the format: 35 featured stories and 15 vignettes linked to chapters that connect them to other trailblazers in the book. It was all the more appropriate since 2022 marked the golden anniversary of Title IX. Having the chance to highlight 50 women for 50 years, with Pat Summitt at the center, remains the honor of a lifetime.

Chapter 16: You manage to weave these stories with a specific public policy theme (Title IX), in the process making a larger argument about how public policy actually works. Can you say more about what you think the book teaches us about public policy?

Chapter 16: You manage to weave these stories with a specific public policy theme (Title IX), in the process making a larger argument about how public policy actually works. Can you say more about what you think the book teaches us about public policy?

Pethel: In the introduction to the book, I set up the context leading to the passage of Title IX in 1972, including some larger policy issues connected to the Educational Amendments of 1972 — things like compliance or enforcement, how Title IX evolved, and how it’s been used a bit as a political football (pardon the sports pun). In the conclusion, I discuss some pressing concerns still relevant for Title IX today (the transfer portal, the NCAA’s use and abuse of college athletes’ images and likenesses, transgender issues, etc.). I didn’t go too deeply into those concerns because I wanted the book to be about personal stories, human stories.

The story of Title IX does provide something of a lesson in civics. I quote a constitutional scholar in the book who argued that support for Title IX has long been wide but often shallow. When it passed in 1972, suddenly people figured out that even though words like “sports,” “athletics,” and “gender” were not listed in the 37 words of that section of the law, the most tangible result was going to be women’s sports. Clearly, here was the most room for growth, right?

At that point, support for women’s athletics in educational institutions was effectively zero. Therefore, any support approaching equity would appear exponentially great in its impact. Title IX went from something relatively uncontroversial when it passed to something considered controversial as lawmakers, pundits, and those affected by the law argued about implementation. There are two central questions that politicians and activists, on both sides of the aisle, have argued over since 1972: What does equity and equality mean for women in higher education, and more specifically women in sports, and how does that relate to balances of power within and beyond the government?

Yet, I hope my book shows that public policy is foremost a living concern. Especially in the case of Tennessee. I tell a story about how the women featured in the book took up spaces the law could only suggest, building institutions, making the policy dynamic. In the process, they built a lasting legacy for themselves and laid the groundwork for future generations. These women were the embodiment of Title IX and the law more broadly.

So I think the book teaches us, yes, public policy is ongoing, fluid, and contested, but it can become a lasting testament to people who build institutions and work in them. Title IX in Tennessee testifies to the power of education, of sports, and the empowering combination of both in the lives of young women. We should recall that Title IX’s impact was hardly a foregone conclusion when it first appeared. Women had to give meaning to the letter of the law. They actualized the words in that document. And they had been laying the groundwork to do just that.

Consider, for example, the Tennessee women who built and then launched a statewide competitive network for women’s athletics three years before Title IX, the Tennessee College Women’s Sports Federation (TCWSF). They cultivated relationships, created alliances, and were strategic about what battles to fight and how to fight them. Tennessee women were uniquely prepared for the arrival of Title IX, and they continued that work for decades after the law was passed, up to the present.

These women also had a lot to prove. On one hand, they had to show that women’s athletic programs were not a threat to men’s sports. But on the other, they had to demonstrate that women’s sports deserved respect and recognition. John Wooden is credited with saying that winning breeds winning. These Tennessee trailblazers built teams and developed programs such that the people in our state eventually embraced women’s sports. They created loyal fan bases by setting the bar for excellence on and off the field or court.

In other words, success was contagious. It became a source of pride and even statewide identity, and not just in Tennessee. If we forget stories like this, we risk losing an essential chapter in the longer arc of American social and cultural history, not just sports history. Because here are examples of the tangible things that Title IX did, with clear and positive outcomes for the people involved. After all, there’s abundant evidence of a correlation between career success for women in all walks of professional life and participation in high school or college athletics.

Chapter 16: Maybe among the most important things historians do is recover stories that most people would otherwise never have known or might have forgotten. To your mind, which figures in this group do you think most merit remembering and recovery from relative obscurity and why?

Pethel: I think about women like Lucia Jones. Lucia grew up in South Carolina and played boys’ baseball undercover as a boy until she hit 13 and people figured out the ruse. But along the way she began teaching swimming lessons and realized that she loved to teach. She then attended Winthrop University in South Carolina as a physical education major, becoming a remarkably good badminton and volleyball player, and she also became a certified official/referee. She later joined the PE faculty at the University of Tennessee at Martin and shaped the lives of generations of students. She took their volleyball program from an intramural activity to regional powerhouse. She started an extremely successful coed badminton program, which practiced from 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. because it was the only time the gym was free. All the while she served as an official for women’s basketball. To indulge a play on words, she served to others on the badminton and volleyball courts, all the while serving others behind the lines as an official and a teacher. There are lots of people like Lucia Jones in this book.

Bettye Giles, a matriarch of women’s sports in Tennessee also comes to mind. (She turned 94 in January 2023.) She was co-founder of the TCWSF and a mentor to Pat Summitt. There are people like Joan Cronan, who spent 30 years as an athletics director at UT Knoxville and continues to be an ambassador for all women’s sports. Joan remains influential, charismatic, and a class act from top to bottom. There’s Teresa Lawrence Phillips, the first Black female athlete to play at Vanderbilt. She eventually worked as an assistant coach at her alma mater before moving on to Fisk and then Tennessee State University, becoming athletics director at TSU in 2002, a position she held until her retirement in 2020. I could go on. The list of compelling people and stories likely unknown to most potential readers is probably the prime mover of the entire project. I’ve briefly mentioned 4 — there are 46 others.

Chapter 16: You did a remarkable number of interviews for this book and ended up with great material. As someone who doesn’t do much oral history, I’m curious about methods. What sort of an approach do you think gets the best results?

Pethel: Before this book, my work focused largely on cultural and intellectual history, with most research about higher education focused on the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Needless to say, oral history isn’t something one does when working in that time period, so there was a great deal of experimentation and a relatively steep learning curve in conducting and transcribing interviews. Ironically, had the COVID-19 pandemic not come along, this book would have been very different, or at least looked more like the leaner version I had first envisioned. The pandemic accelerated our collective learning curve in a way that probably nothing else would have. The majority of the people I interviewed for this book were over 65, not a demographic category well known for their familiarity with, say, cloud-based meeting platforms. Yet, as we know, to communicate during the pandemic, people of all kinds learned how to connect through different forms of technology. Suddenly, I could expand the list and scope of interviewees regardless of age or geography. Interviews came from 17 U.S. states and even far-flung places like Australia and Japan. I recorded, mostly using Zoom, and transcribed from there.

Along the way, my oral history skills inevitably developed. And I managed to collect a trove of secondary and primary source material despite some archives being closed to researchers for nearly two years. Fortunately, some of the women I talked to went through their own personal collections and sent me boxes of original primary source documents! The research process for this book was amazing. No one could have predicted how the world would change so much in such a short period of time, and with such terrible consequences for so many. Yet, in one of those ironic turns of the historical wheel, I ended up with rich source material. I do mean to formalize and clean up these transcripts once the dust settles, and I hope to deposit them in the appropriate archive to preserve this history for others in the future.

Chapter 16: This book combines a love of history and story with a genuine love of sports. How did you develop those passions?

Pethel: I’ve thought, played, and written about sports for a long time. As I came of age in the 1990s, I was fortunate that my parents fully supported my athletic endeavors. I was also fortunate to play on some really good teams in high school, specifically on the varsity basketball team as point guard. (As a freshman, I played in the 1991 Georgia High School State Championship. That team is being honored on February 3 at Rome High School, and I will be seeing former teammates for the first time in over 25 years.)

Later, as an undergrad honors student at UT Knoxville, I wrote my senior thesis about the first generation of women athletes in Knoxville. So I’ve been interested in the intersection of gender and sports for some time. The story of women’s athletics in Tennessee worked in two stages. Women played sports in high schools and colleges in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, only for women’s athletics to go mostly dormant following a cultural backlash in the 1920s. Competitive intercollegiate women’s sports reemerged in the 1960s. Title IX was my chance to tell the second half of a larger story that had long interested me.

Over the course of two years’ work on this book, I conducted over 40 interviews with women aged 20 to 93, and this book tells all of their stories. Of course, Pat Summitt is in the title of the book. I realized that, beyond the three chapters specifically dedicated to her, I was also writing a book about her life because nearly everyone I interviewed had a Pat Summitt story. They were coached by her, worked with her, or were on a team with her. All were inspired by her, as was I.

I have a Pat Summitt story too, which I mention in the book’s acknowledgments. I met her in spring 1998 after the Lady Vols had finished a perfect season, capturing their third NCAA championship in as many years. She had written a book about the team’s season called Raise the Roof. A UT senior at the time, I went to a book signing on campus. I handed her the book, and we traded small talk. I told her I’d just finished my history honors thesis. She asked what it was about, and I said it was about the first generation of female athletes in Tennessee. That caught her attention. She looked up and asked about the 1970s, and I replied with something like, “No, way back. knickers, not Nike.”

Pat smiled and said, “I’d like to read that.”

I know that’s just a thing people say, but I like to think she meant it. Then she asked about my plans. I told her I was headed to Atlanta to law school. So she inscribed my book: “To Mary Ellen, raise the roof in Law School, Pat Summitt.”

Obviously law school didn’t work out for me. History was my true passion, teaching and writing and storytelling. But as I put the final touches on this project, I couldn’t help but think about that brief meeting with Coach Summitt. I imagined going back in time, telling Pat that one day I’d write a book about her generation with her name in the title.

Pat Summitt’s legacy looms large over Tennessee, yet she was only one of many who shaped women’s sports in the state and in turn across the nation. Writing this book became a full-circle moment for me as I conducted interviews and research and drafted chapters. I grew increasingly aware and appreciative of my own history. I am a daughter and a beneficiary of Title IX, too. We all are in this country. Equity and inclusion are wins for everybody — women, men, girls, and boys.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses on American culture and thought. He is also a regular blogger for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).