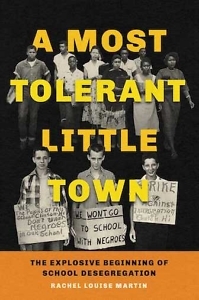

Recalling the “Clinton 12”

Rachel Louise Martin chronicles the battle to desegregate an East Tennessee high school

A few chapters into A Most Tolerant Little Town, Rachel Louise Martin tells what happened on a Sunday morning in the fall of 1956, a few days after 12 Black students attempted to desegregate Clinton High School in East Tennessee.

One of those students, Gail Ann Epps, was worshipping with her family at Mt. Sinai Baptist Church when congregants felt “a distant shudder through the floorboards … a vibration from somewhere deep down in the earth.”

Running to the windows, they saw tanks pulling into their small town, followed by armored personnel carriers, jeeps, and helmeted soldiers carrying automatic rifles.

The Black families felt relief. After a tumultuous week, Governor Frank G. Clement had called out the National Guard. Help had come, finally.

Surprisingly, few know the Clinton High story. Although it was the first state-run public high school in the South to attempt court-ordered desegregation in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the events in Clinton have largely gone missing from history, overshadowed by more urban civil rights stories such as that of the “Little Rock Nine,” who desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957.

Martin, the author of Hot, Hot Chicken: A Nashville Story, discovered Clinton in 2005 while working as a research fellow at Middle Tennessee State University. She continued the project as a doctoral student at the University of North Carolina, eventually spending almost 18 years interviewing former students, families, administrators, and townspeople while delving into historical documents and contextual material.

Not everybody wanted to talk to her. “Honey, there was a lot of ugliness down at the school that year; best we just move on and forget it,” one white woman told her. Fortunately, Martin didn’t forget. Instead, she pieced together some 60 interviews, presenting events from multiple perspectives to show what people, Black and white, grappled with in that place and time.

For example, Wynona McSwain (who sometimes spelled her name Winona) had been trying to improve local education long before she and her husband Allen filed McSwain v. Anderson County, the case that led to Clinton High’s desegregation. She knew teachers at the Black schools did their best, but classes were overcrowded and buildings and materials inferior. Hopefully her daughter, Alvah Jay, could go to the more prestigious Clinton High.

For example, Wynona McSwain (who sometimes spelled her name Winona) had been trying to improve local education long before she and her husband Allen filed McSwain v. Anderson County, the case that led to Clinton High’s desegregation. She knew teachers at the Black schools did their best, but classes were overcrowded and buildings and materials inferior. Hopefully her daughter, Alvah Jay, could go to the more prestigious Clinton High.

Meanwhile, whites fell into two broad camps. The staunch segregationists formed multiple “councils” to maintain whites-only schools. Some were led by John Kasper, a Columbia-educated “carpetbagger” and devotee of controversial poet Ezra Pound, but Kasper was later drummed out of town as locals formed their own groups. One was started by teen girls who reasoned that since it wasn’t socially acceptable for females to fight with knives, they would oppose desegregation with their own council.

Segregationists remained largely quiet the first day as the 12 walked from “Freedman’s Hill” to the school, but they grew increasingly violent as the week wore on. Some formed a gauntlet along the Black students’ route, carrying signs with racial epithets. Inside the school, they harassed, tormented, and sometimes physically attacked their new classmates. Meanwhile, white mobs downtown attacked any Blacks who happened to pass through. Several small bombs went off. Finally, the sheriff realized he needed reinforcements and called the governor.

The other white camp, though, realized desegregation was the law of the land, whether they liked it or not. The Sunday that Epps saw the tanks arriving, Reverend Paul Turner told his white congregation over at First Baptist, “It is important to be a Christian first and a segregationist second, not a segregationist first and a Christian second.” His point was radical, since some whites believed the Bible mandated segregation, though others saw it as morally wrong, despite cultural pressure.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Martin’s book is the way she shows how white views differed and evolved over time. Turner eventually offered to escort the Black students to school, thinking he could protect them, but was savagely beaten by segregationists. Typing teacher Margaret Anderson, meanwhile, tried to help the Black students acclimate. Though she accepted desegregation reluctantly at first, she championed it in two lengthy New York Times articles in the early 1960s.

In spring 1957, Bobby Cain, one of the 12, became the first Black student in the South to receive a diploma from a previously all-white school, although some white students tried to ambush him as he walked off the stage. He attended Tennessee State University debt-free, thanks to contributions from across the country. Epps graduated, too, but others among the 12 weren’t so lucky. One was expelled when he defended his brother in an attack by whites, and two families, including the McSwains, left for California to escape the turbulence. The following fall, Clinton High was bombed.

For all its nuanced exploration of a time that seems both remote and sadly familiar, A Most Tolerant Little Town pulls no punches. In “A Note on Language,” Martin says she retains racial slurs in quotations to illustrate “how racism infected white American culture in the 1950s.” It is a bold choice, but the Clinton story would not be well served by euphemism.

Martin does not believe the story is over. Representations of Black children entering schools, including the statues now at Clinton’s Green-McAdoo Cultural Center, are misleadingly triumphant, she argues, allowing people “to pretend that segregation and racism no longer exist.” Instead, she distinguishes “desegregation” (attending school alongside one another) from “integration” (sharing friendships and the same opportunities in a place where all feel welcome).

True integration, she contends, “is an experiment we have yet to try.”

*[This article has been updated to clarify Clinton High’s status as the first state-run public high school to desegregate in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education.]

Jane Marcellus is a writer whose published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism. Her work was listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020. She is a former professor at Middle Tennessee State University.