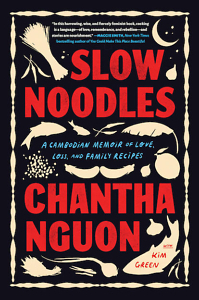

Recipes for Survival

Chantha Nguon’s Slow Noodles turns dark history into hope

The imperative is a verb mood that indicates an action is required. A recipe, for example, is written in the imperative, describing a series of actions necessary to achieve the desired outcome. In Slow Noodles: A Cambodian Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Recipes, author Chantha Nguon (with Nashville co-writer Kim Green) explores recipes for survival, attempting to define the imperative — what’s needed for a person, and a country, to endure unimaginable adversity.

The ingredients list for this book is daunting, containing genocide and war, family trauma, fear, resistance, terror, and determination. But the final result is full of unexpected flavors of hope, strength, and the sweetness of honoring your memories. Nguon acknowledges that her story is horrific, understanding why many prefer to leave it in the past: “We Cambodians do not like to bare our scars. We share an unspeakable history, so we rarely speak of it. But I will tell my story in these pages, if only to prove that the past cannot be extinguished.” With Slow Noodles, Nguon also passes on the flavors and philosophies from her mother’s kitchen, the place where she learned her first lessons for living.

Growing up in Battambang, Cambodia, Nguon didn’t fully realize the relative privilege her family enjoyed, but she observed her mother (Mae) and older sister sharing their leftovers with neighbors who had less. As a young child, she didn’t fully know how to make rice or noodles herself, but she knew “time equaled love, and love equaled deliciousness,” and that Mae “despised the flavor of shortcuts.” As she watched her mother hold her tongue at her mother-in-law’s contempt, she was learning the Chbab Srey, or “Rules for Women,” a collection of instructive verses written in the imperative: “You must serve your husband/ Don’t make him unsatisfied.” Nguon knew the requirements for Cambodian women meant she must “shine dimly, like a moon, and reflect her husband’s sunlight.”

But all these lessons came before the death of her beloved father, before she and her siblings would flee to South Vietnam to escape the persecution under Lon Nol, before Year Zero and the terror of the Khmer Rouge. Those days came before the fall of Saigon and before the refugee camps and their filth and privation, the hunger and exhaustion that would color so much of Nguon’s future. In each of these experiences, she learned new rules, new imperatives, like the Vietnamese Communist Party slogan – “Work with all your vigor and collect what you need” — or the rules for ration queues, which include “Do not question the logic of the ration queue. There is none,” and “Do not question the Party’s definition of need.”

But all these lessons came before the death of her beloved father, before she and her siblings would flee to South Vietnam to escape the persecution under Lon Nol, before Year Zero and the terror of the Khmer Rouge. Those days came before the fall of Saigon and before the refugee camps and their filth and privation, the hunger and exhaustion that would color so much of Nguon’s future. In each of these experiences, she learned new rules, new imperatives, like the Vietnamese Communist Party slogan – “Work with all your vigor and collect what you need” — or the rules for ration queues, which include “Do not question the logic of the ration queue. There is none,” and “Do not question the Party’s definition of need.”

There were other rules, however. Scattered throughout the book, alongside instructions for making Fried Spring Rolls or Banh Sung, Nguon includes her own unconventional recipes like one called “Silken Rebellion,” which enables “quiet defiance under an authoritarian regime”:

Find the pockets of freedom available to you. Exploit loopholes. Play the role of a defeated subject when necessary. Remain undefeated in the important ways, wherever possible. … Determine what you need and find a way to get it for yourself. It will not necessarily be supplied to you, no matter how earnest the promises.

Like the repeated violence and loss that threatened to overwhelm her, these small acts of self-preservation accrue over time, granting windows of hope that ultimately lead to survival.

Along the way, Nguon’s path aligns with that of her partner Chan, a man who does not require her to observe those long-ago rules of Cambodian womanhood. Instead, it is Chan who, in a particularly difficult moment, offers the harsh but necessary truth that shifts her perspective. When she lags behind the men on an arduous trek through the jungle, he says, “You have to be equal now.” Nguon understood immediately that she didn’t have to follow the Chbab Srey: “And from that moment forward, I was sunlight — strong and fierce.”

Nguon’s story is heart-wrenching, but her strength and ferocity shine through every page of Slow Noodles. Readers will feel Nguon reject the possibility of pity as she faces every impossible terror with determination and depth. She doesn’t deny her sadness or fear or pain, choosing instead to see that “sometimes, sweetness and bitterness are too tangled to separate. … A wound can become a source of power. Pain into strength.” By facing the painful past, Nguon crafts a recipe for a life, one that combines the imperatives from her mother and the evolving definitions of need with renewed hope and purpose.

Sara Beth West got fired from her first job. By her dad. Since then, she’s walked away from many other jobs, including nanny, retail worker, farmhand, choir director, teacher, social media manager, and compost truck driver. Most recently, she left a great job as a public librarian. But the one job that keeps following her around is writer. She writes book reviews and conducts author interviews for Shelf Awareness, Chapter 16, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.