Reckoning with M.L.K. on the Anniversary of His Assassination

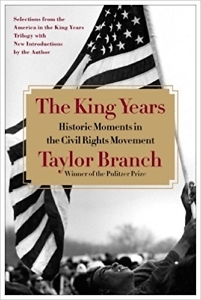

A historian considers Taylor Branch’s The King Years

All three colossal volumes in Taylor Branch’s narrative history of the civil-rights movement contain the same subtitle: “America in the King Years.” A subsequent book, a slim collection of excerpts published in 2013, is titled simply The King Years. As we mark the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis—and wrestle with its meaning for our own time—we might also revisit the core assumption behind that phrase. As Branch contends, “King’s life is the best and most important metaphor for American history in the watershed postwar years.”

King was a radical critic of the nation and its institutions, a man reviled by masses of Americans. The FBI maintained a constant surveillance of him. Presidents from Eisenhower to Kennedy to Johnson kept a wary distance. Many ordinary white Americans rejoiced upon his murder.

King was a radical critic of the nation and its institutions, a man reviled by masses of Americans. The FBI maintained a constant surveillance of him. Presidents from Eisenhower to Kennedy to Johnson kept a wary distance. Many ordinary white Americans rejoiced upon his murder.

It is also true that, as Ella Baker contended, “Martin didn’t make the movement, the movement made Martin.” The foundation of the black-freedom struggle was laid brick-by-brick by black activists, especially at the local level, and those efforts predated the King years. These activists were young and old, women and men. Their struggle continued after King’s death.

Yet King emerged as the preeminent voice and most powerful engine of the civil-rights movement. He crafted a message with moral backbone, marrying the ideals of Christian righteousness and American democracy. By pressing the inclusion of nonviolence into the political tradition, he protested against not only racism but also against militarism and greed. This prophetic figure demanded a “revolution of values,” a new commitment to end the war in Vietnam and to tackle the poverty of forgotten Americans.

One of Branch’s enduring contributions is the way he plops King down among the raging currents of American politics in the 1950s and 1960s. The King Years includes selections from King’s defining historical moments, such as his landmark speeches from the Montgomery bus boycott and the March on Washington, and his role in the march from Selma to Montgomery.

But Branch also chooses excerpts that highlight the forces buffeting King. We witness the audacious efforts of the Freedom Riders and grassroots organizers in Mississippi. We enter the contentious political conventions of 1964, which forecast the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties. We see the rise of Black Power, the crisis of Vietnam, the vision of the Poor People’s Campaign, the detour toward Memphis.

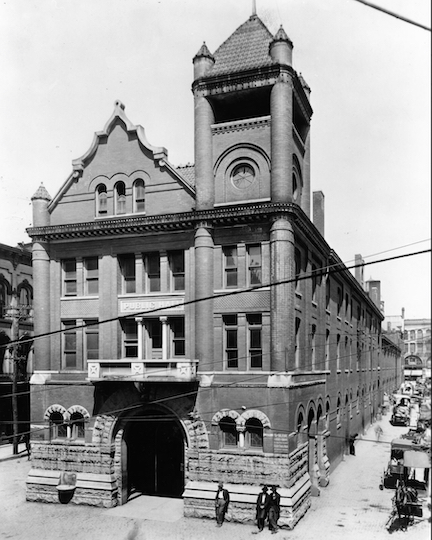

The volumes in Branch’s trilogy, which together comprise more than 2,000 pages of text, provide an astonishing level of detail on King and his world. It is the product of a life’s work, including thousands of interviews and research in hundreds of archival collections. The Taylor Branch Collection in the Special Collections at the University of North Carolina contains about 60,000 items from Branch’s research.

The volumes in Branch’s trilogy, which together comprise more than 2,000 pages of text, provide an astonishing level of detail on King and his world. It is the product of a life’s work, including thousands of interviews and research in hundreds of archival collections. The Taylor Branch Collection in the Special Collections at the University of North Carolina contains about 60,000 items from Branch’s research.

The first volume, Parting the Waters, won the 1989 Pulitzer Prize in history. Beginning in 1954 with the Montgomery bus boycott, the book stays close to King. It traces his emergence as the nation’s moral conscience, climaxing with the epic events of 1963, including the Birmingham campaign. Yet Branch also makes space for the movement’s critical, lesser-known champions, such as Vernon Johns, King’s predecessor as pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

Pillar of Fire, published in 1998, takes a wider angle, with narrative threads that feature figures who stalked King in the mid-1960s, defining the political boundaries in which he operated. Malcolm X looms large here, as does FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. In subtler ways, Branch highlights the central role of black women in the civil-rights struggle, such as Nashville’s Diane Nash and Mississippi’s Fannie Lou Hamer.

Branch finished the trilogy in 2006 with At Canaan’s Edge, which moves from Selma in 1965 to Memphis in 1968. In this final volume, the story grows more chaotic, reflecting the times. It bounces from Lyndon Johnson’s tortured handling of the Vietnam War to Stokely Carmichael’s cry for Black Power to a rising white backlash and a disintegrating liberal spirit.

Still, King stands at center stage, flawed and torn, courageous and idealistic. Branch reconstructs his journey with striking, excruciating detail up through April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel. There, Branch writes, “King stood still for once, and his sojourn on earth went blank.”

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith