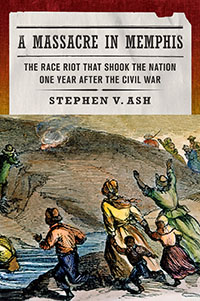

Reconstructing a Tragedy

Stephen V. Ash describes the Memphis Massacre of 1866, a brutal episode with profound implications for race and democracy

From May 1 to May 3, 1866, Memphis erupted in racial violence, resulting in at least forty deaths. In his comprehensive and compelling book A Massacre in Memphis, Stephen V. Ash describes the horror in grim detail. He writes of black people shot in the face, of pregnant women raped, of neighborhoods burned to ashes, of open declarations to kill as many African Americans as possible. He also puts the carnage in context, explaining both its roots and its impact with skillful attention to detail.

Ash, professor emeritus of history at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, is a widely published historian of the Civil War and nineteenth-century Tennessee. Prior to his lecture at Rhodes College on March 17, 2016, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Ash, professor emeritus of history at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, is a widely published historian of the Civil War and nineteenth-century Tennessee. Prior to his lecture at Rhodes College on March 17, 2016, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: The story of these three days is shocking, even for someone who has studied other instances of racial violence. Why write about the Memphis Massacre? What do we gain by delving into this terrible history?

Stephen Ash: Confronting the ugliest episodes of our past is essential to fully understanding that past. I know that parts of my book are painful to read. Believe me, they were painful to write. But if historians skirt around the ugliness, or sugarcoat it, they convey a false impression of the past that can do real damage in the present. There are people in this country today who downplay or even deny the suffering endured by black Americans in the era of slavery and emancipation. That undermines the legitimacy of the black quest for justice that continues into our own time. Their misrepresentations must be refuted.

This is not to say that my book is politically motivated or propagandistic. Like all professional historians, I try to give as factual and unbiased an account of past events as possible. The atrocities in Memphis in May 1866 that I recount actually happened; the historical record is incontrovertible.

Chapter 16: The first section of your book lays out the politics and culture of Memphis on the eve of the violence. To understand the massacre, what do we need to understand about Memphis?

Ash: The riot grew out of deep cleavages of race, class, ethnicity, and politics. Some of these predated the Civil War, and some emerged after it. The black population of Memphis, about 4,000 in 1861, had by 1866 mushroomed to perhaps 20,000. The freed people eagerly embraced the opportunities that emancipation offered: establishing churches and other communal organizations, staking a claim to jobs, bargaining with their employers, abandoning the obsequious deference that whites expected from them, and declaring their desire for equality under the law, even the right to vote.

That black influx inflamed the prejudices of the city’s working-class Irish immigrants, who would be the main perpetrators of the riot. After the war, the Irish took control of the city government because the native-born whites, who had supported the Confederacy during the war, were disfranchised by decree of the Unionist-controlled state government. The mayor was Irish, as were most of the city aldermen and almost all the firemen and policemen. The police, who were notoriously unprofessional and undisciplined, were especially antagonistic to the ex-slaves—and most especially to those who served in the U.S. Army, a large force of whom was posted in the city during and after the war.

Both the Irish and native-born white Southerners also despised the Northerners who had come to Memphis, some of them with the purpose of “uplifting” the freed people. These U.S. Army personnel, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, businessmen, ministers, and teachers were viewed as meddlers who encouraged dangerous ideas among the freed people with talk of racial justice and equality.

The city’s whites defined emancipation very narrowly. To them it meant simply that black people could no longer be bought and sold; in all other respects they should remain hewers of wood and drawers of water for the white race. Every incident of black crime, rowdiness, or assertiveness in the postwar months—and there were plenty of each—was further evidence, as whites saw it, that emancipation had been an egregious mistake.

By the spring of 1866 the racial tension in the city was so palpable that many people thought an explosion of some sort inevitable. White-black fracases on the streets multiplied. Black men were heard muttering that they would no longer tolerate police abuse. White Memphians, convinced that a surging tide of black crime and violence was about to inundate them, insisted that the freed people must be brought to heel and that their Yankee friends must go.

By the spring of 1866 the racial tension in the city was so palpable that many people thought an explosion of some sort inevitable. White-black fracases on the streets multiplied. Black men were heard muttering that they would no longer tolerate police abuse. White Memphians, convinced that a surging tide of black crime and violence was about to inundate them, insisted that the freed people must be brought to heel and that their Yankee friends must go.

Chapter 16: Before mob violence, there is often an incident that sets a match to the tinder, bringing the underlying tension to the surface. In the case of the Memphis Massacre, what was that incident?

Ash: On the afternoon of May 1, in a predominantly black neighborhood known as South Memphis, a few dozen black soldiers—former soldiers, that is, having been mustered out of service the day before, but still in uniform—were hanging out on the sidewalk sipping whiskey from canteens, getting louder as the day went on. A squad of four policemen ordered them to disperse. The police had no actual authority here, since they were just outside the city’s boundary, beyond police jurisdiction. The ex-soldiers refused to leave. Some taunted the policemen. “Hurrah for Abe Lincoln,” one called out. A policeman replied hotly that Lincoln was “dead and damned.” Tempers rose on both sides. Getting nowhere, and heavily outnumbered, the policemen retreated up the street.

The incident should have ended there, but some of the blacks followed the policemen, cursing and shoving them and brandishing clubs and rocks. Then one fired a pistol into the air, intending to speed the policemen’s retreat; a few others did the same. The policemen thought they were getting attacked. They halted, drew their own pistols, and fired into the crowd, sparking a shootout. One policeman was wounded in the fusillade, and another a few moments later as he fled the scene.

The word on the street was that the blacks in South Memphis were in open rebellion, intending to slaughter the whole white population. Mobs of armed white men, almost all Irish and led by policemen, marched from downtown to South Memphis. There they opened fire indiscriminately on black men, women, and children. And so the riot began.

Chapter 16: In the middle section of the book, which describes the terror with shocking precision, your voice switches from past tense to present tense. What guided that choice?

Ash: Although I had tried my hand at narrative history in two previous books, I had never employed the authorial device of the present tense. But I had seen it used to powerful effect in a couple of works of narrative history dealing with the Civil War—Albert Castel’s Decision in the West and Daniel Sutherland’s Seasons of War—and so I decided to give it a try. This seemed the best way to convey the drama of the riot, the kaleidoscopic rush of events, the moment-by-moment contingency and confusion, and the sheer horror.

Chapter 16: There is a canyon-wide gap between the version of events presented in the Memphis newspapers at the time and the actual history of the massacre. Why? How might it speak to the larger divisions in Memphis society?

Ash: Almost all the Memphis newspapers were controlled by ex-Confederates. Amidst the confusion of the riot, these papers reported that blacks, spurred by meddling Yankees, were the rioters. “There can be no mistake about it,” the Daily Argus editorialized on May 2, “the whole blame of this most tragical and bloody riot lies . . . with the poor, ignorant, deluded blacks,” who “have been led into their present evil and unhappy ways by men of our own race.”

As time passed and three federal investigations destroyed the myth that blacks were the perpetrators, the newspapers deflected blame by pointing out (accurately) that the rioting was the work of the city’s Irish underclass, not the ex-Confederates. Moreover, they insisted that the freed people had brought the trouble on themselves by their intolerable misbehavior and outrageous demands since gaining freedom. The carnage of May 1-3, though regrettable, had taught a salutary lesson. As the Daily Avalanche proclaimed, “The negroes now know, to their sorrow, that it is best not to arouse the fury of the white man.”

Chapter 16: How should we understand the black community in Memphis throughout this ordeal? They are obviously victims, yet you do not portray them as passive.

Stephen Ash: The suddenness and randomness of the mob assaults (there were many over the three days of rioting, in various parts of the city) almost invariably left the victims helpless to resist. In a few instances, armed black men fought back, but such ad hoc resistance accomplished little, as the rioters could scatter and reappear soon after in another place.

Aware that the police were themselves among the rioters, black Memphians had to appeal for military protection. (There were several companies of white U.S. Army troops posted in the city.) Despite repeated requests by blacks and whites to deploy his troops, however, the military commandant, General George Stoneman, declined to intervene, making various excuses until the rioting reached such intensity that he could no longer remain aloof. Timelier action on his part could have saved many lives. He was never called to account for this dereliction of duty. Nor was any rioter ever punished.

Chapter 16: What is the legacy of the Memphis Massacre? Did it shape national politics during Reconstruction?

Stephen Ash: The massacre played a role in the great battle over Reconstruction policy then being waged in Washington. President Andrew Johnson maintained that the rights and privileges of the former slaves should be determined by the white South, that federal protection for freed people was unnecessary and unconstitutional, and that seceded states should be quickly restored to the Union with minimal conditions. But members of Congress who opposed his policy brandished the Memphis Massacre as evidence. Congress subsequently overturned Johnson’s policy, imposed stern conditions for readmitting the former Confederate states, and enacted far-reaching measures to protect the freed people, culminating with the 14th and 15th Amendments. At every step along the way, the specter of the Memphis Massacre loomed large.

Chapter 16: You end the book with a plea for a public memorial to the victims of the Memphis Massacre. Would this symbolic gesture make a difference? If so, why?

Stephen Ash: A public memorial would serve several important purposes. First, it would stand as a reminder that racism and racial violence have always been a part of American life and have profoundly influenced our nation’s history—a fact too often swept under the rug in public discourse. Second, it would draw attention to the common folk of America’s past, the people who led unremarkable lives, who toiled quietly and anonymously in an often unfriendly world. They too have shaped our history, but they are often forgotten by a modern public that relishes tales about great men and battlefield heroics. Third, it would raise awareness about the era of Reconstruction, the sesquicentennial of which is now upon us. This crucially important part of American history is generally overshadowed in the public mind by the Civil War; outside of the writings of professional historians, it rarely receives its due. Reconstruction should be a part of every American’s understanding of our past.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.