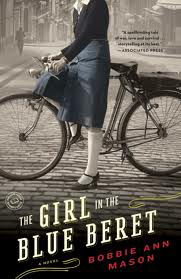

Regaining Altitude

Bobbie Ann Mason returns with a remarkable World War II novel about a downed aviator in Nazi-occupied France

”As the long field came into view, Marshall Stone felt his breathing quicken, a rush of doves flying from his chest.” Thus begins Bobbie Ann Mason’s The Girl in the Blue Beret—with a delicate image of fluttering flight coupled with the sense of being bound to an earth that is at once melancholy and nurturing. The contrasts between being rooted and aloft, despairing and elated, chastened and pardoned persist in this delicately crafted novel, which is simultaneously a tale of adapting to old age, a charming romance, a food-and-wine tour of Paris and Provence, and a spellbinding World War II suspense thriller. Mason based The Girl in the Blue Beret on the experiences of her late father-in-law, a bomber pilot smuggled by the Resistance over the Pyrenees into Spain after being shot down in Belgium. Coupling this inspiration with careful research (illuminated in the author’s acknowledgments and a helpful bibliography), Mason has produced a richly satisfying page turner and an artful literary novel worthy of a wide audience and a prominent place in its acclaimed author’s award-winning body of work.

The Girl in the Blue Beret begins in 1980, with Marshall Stone in the midst of the last journey of his professional career. At sixty, Marshall is being forced into an uneasy and unwelcome retirement. “The airline didn’t want rickety, half-blind ancients at the controls,” he laments. “Screw the airline, he thought now. Roaming Paris, he composed the thousandth rebuttal he would never send in: Since being let go on account of advanced age and feebleness, I’ve been forced to adopt a new career. Henceforth, I shall guide hikers up Mont Blanc, and on my days off I’ll be going skydiving.” Marshall’s professional peak spanned the glory days of airline travel, when pilots were regarded as dashing and glamorous; flight attendants were still stewardesses required to be svelte, single, and under the age of thirty; and no passenger would dare board a plane wearing blue jeans. Indeed, Marshall himself is still physically vigorous, charismatic, and attractive to a diverse range of women, with or without his gold-trimmed pilot’s uniform. But Marshall’s dilemma, it turns out, is no mere identity crisis borne of retirement. For decades, his absorption in his career has obscured a complex web of unresolved feelings and broken ties from the war years, when, after a bombing run over Frankfurt aborted by heavy German anti-aircraft fire, he crash-landed the B-17 “Dirty Lily” in a field in Belgium.

Marshall’s story begins on the stopover before his last transatlantic flight as a pilot, visiting that “long field,” both strange and familiar. To his surprise, he encounters faces he remembers, despite the passing of thirty-five years. Shaken and inspired by the experience, Marshall resolves to return to France and reconnect with the members of the French Resistance—people who hid him from the Nazis, eventually escorting him and dozens of other downed American aviators across the Pyrenees into Spain, sometimes paying for their efforts with their lives. He is particularly determined to find the young girl who guided him through Paris all those years before—the girl in the blue beret.

Marshall’s story begins on the stopover before his last transatlantic flight as a pilot, visiting that “long field,” both strange and familiar. To his surprise, he encounters faces he remembers, despite the passing of thirty-five years. Shaken and inspired by the experience, Marshall resolves to return to France and reconnect with the members of the French Resistance—people who hid him from the Nazis, eventually escorting him and dozens of other downed American aviators across the Pyrenees into Spain, sometimes paying for their efforts with their lives. He is particularly determined to find the young girl who guided him through Paris all those years before—the girl in the blue beret.

Given that Mason’s story was inspired by her own father-in-law’s war experiences, it’s not surprising that her portrayal of Marshall and his fellow veterans is generous, but she never falls into the melodrama that undermines so many efforts at memorializing the World War II generation. Mason seems particularly insistent on disabusing her readers of any gauzy, sanitized images of the flyboys as All-American virgins holding out for their sweethearts back home. While stationed in London, Marshall and his fellow flyers pursue “sex-starved” English girls with abandon while simultaneously writing tender letters home to their wives and girlfriends. Both before and during his marriage, Marshall followed his libidinal urges, regretting his delusions too late to change his behavior: “He had rationalized infidelities to Loretta by telling himself that his sporadic overseas flings were an alternate reality,” Mason writes. “He believed she would understand that. He could come home and enter into her world as if he had never been away. He was a false-hearted fool.”

Still, with his wife two years deceased, Marshall is now open to the possibility of redemptive love, which presents itself in the figure of two diversely aged but uniformly attractive and amply breasted Frenchwomen he encounters on his quest to reconnect with the ghosts of his past. Indeed, were The Girl in the Blue Beret written by, say, Philip Roth or Norman Mailer, some of its more romantic elements could easily be misread as a geriatric wish-fulfillment fantasy. Instead, Mason describes Marshall’s amorous urges and recollections as matter-of-fact, unsentimental aspects of a man who has spent much of his life literally aloft, only to find himself simultaneously grounded and up in the air.

In terms of plot and narration, the early 1980s setting liberates Mason from certain practical constraints: cell phones and Google aren’t around to substitute for old-fashioned sleuthing, for one thing. More importantly, in 1980—with World War II veterans still mostly occupying the work force and their Baby Boom children just beginning to get past the age of rebellion—the world had yet to really celebrate and memorialize the Greatest Generation. Hence, a man like Marshall could go into retirement somewhat anonymously, lacking a true sense of the significance of his service, adrift and unsure of himself. The root of Marshall’s crisis is his sense that, having only ten missions under his belt before being shot down over Belgium, his contribution to the war effort was insufficient, that he doesn’t deserve to be regarded as a hero. Mason’s seminal first novel, In Country (1985), captures a similar state of post-war malaise during the Vietnam era, a condition that briefly echoes through The Girl in the Blue Beret. Marshall Stone has yet to experience the catharsis brought on by Tom Brokaw, Saving Private Ryan, and Schindler’s List. He comes to France in search of old names and faces, but mostly, in search of himself.

In terms of plot and narration, the early 1980s setting liberates Mason from certain practical constraints: cell phones and Google aren’t around to substitute for old-fashioned sleuthing, for one thing. More importantly, in 1980—with World War II veterans still mostly occupying the work force and their Baby Boom children just beginning to get past the age of rebellion—the world had yet to really celebrate and memorialize the Greatest Generation. Hence, a man like Marshall could go into retirement somewhat anonymously, lacking a true sense of the significance of his service, adrift and unsure of himself. The root of Marshall’s crisis is his sense that, having only ten missions under his belt before being shot down over Belgium, his contribution to the war effort was insufficient, that he doesn’t deserve to be regarded as a hero. Mason’s seminal first novel, In Country (1985), captures a similar state of post-war malaise during the Vietnam era, a condition that briefly echoes through The Girl in the Blue Beret. Marshall Stone has yet to experience the catharsis brought on by Tom Brokaw, Saving Private Ryan, and Schindler’s List. He comes to France in search of old names and faces, but mostly, in search of himself.

Bobbie Ann Mason is most frequently thought of as the great chronicler of her native state of Kentucky, one of the finest authors of regional American fiction. Along with Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, and Tobias Wolff, she is also considered a leading voice of the mid-1980s boom of the minimalist school of literature now known as “Dirty Realism.” She is equally adept, however, at taking her voice abroad, and her delicate, loving descriptions of Paris, Provence, and the Pyrenees make The Girl in the Blue Beret pleasurable both as a travelogue and as a historical mystery. She delights in detailed descriptions of the many meals Marshall enjoys and the many cups of coffee and glasses of wine he quaffs in a variety of locales urban and rural, public and domestic. The figures he encounters from his past reveal an enviable portrait of middle-class French life, especially in the pastoral setting where he finally discovers Annette, the elusive girl in the blue beret.

Through her, Mason introduces a much neglected aspect of the World War II narrative: the hardships endured by the women who served the French Resistance, many of whom lost their husbands and lovers to the work camps, women who suffered the predictable atrocities we would all prefer to pretend could never happen. Her story, understated but nevertheless rousing and deeply moving, enables The Girl in the Blue Beret to transcend the easy classifications of World War II fiction, asserting a new and powerful definition of heroism that lingers long after the last page.

[This review appeared originally on October 24, 2011.)

Bobbie Ann Mason will appear at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13. All festival events are free and open to the public.