Remembrances of Knoxville Past

Linda Behrend revives Anne Armstrong’s stories of her adopted hometown in the late 1800s

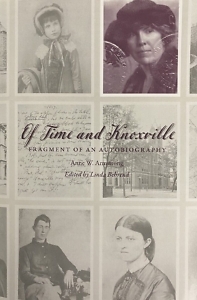

Linda Behrend has dedicated more than 20 years to studying the life and writing of longtime Knoxville resident Anne Wetzell Armstrong (1872-1958). Of Time and Knoxville: Fragment of an Autobiography is Armstrong’s memoir, restored and thoroughly researched by Behrend, focused on her reminiscences of life in Knoxville in the late 1800s. As Behrend mentions in her introduction, Armstrong credits the impetus for writing (quite fondly) about her chosen hometown to this remark by John Gunther: “Knoxville is the ugliest city I ever saw in America, with the possible exception of some mill towns in New England.”

Behrend, who retired from the University of Tennessee, where she was an assistant professor and collections development librarian, aimed to keep the original text intact, with minimal cuts or corrections, and her extensive annotations provide accurate context for the stories from Armstrong. Of the little-known author, who published two novels during her lifetime, Behrend writes, “We can be glad that her ‘tell-all’ memoir survived to give us such a vivid picture of Knoxville as it was just before the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Behrend, who retired from the University of Tennessee, where she was an assistant professor and collections development librarian, aimed to keep the original text intact, with minimal cuts or corrections, and her extensive annotations provide accurate context for the stories from Armstrong. Of the little-known author, who published two novels during her lifetime, Behrend writes, “We can be glad that her ‘tell-all’ memoir survived to give us such a vivid picture of Knoxville as it was just before the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Linda Behrend answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You first heard about Anne Wetzell Armstrong decades ago while working in the East Tennessee State University archives. In the preface, you write, “The more I learned, the more interested I became.” What was it that originally piqued your interest? How did this project expand into, in some ways, the great work of your life?

Linda Behrend: I found it very hard to believe that I had never heard of her before that time. I had a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and had read, extensively, most modern American literature. Not only had she grown up in Knoxville (where my mother was from and where I visited often as a child), but she had also lived during her adult life in upper East Tennessee, where I grew up. I had known since I was in the 7th grade that I was meant to be a writer, and here was one, although of a different generation, who lived almost in my own back door when I was growing up!

The Knoxville connection was probably the strongest, but her interests and writings about the mountain people also attracted me. I had parents who were nature lovers (as hers were), and when I was growing up, we spent a lot of time in the mountains and up in the “hollers.” Plus, for years I had been going to Barter Theatre and other events in Abingdon, Virginia, where she spent her final years and where most of her plays had been produced. She and I have other things in common and, for a long time, I have had the feeling that I have become her Doppelgänger.

As I collected Anne Armstrong’s works and reviews of her works, I realized that she does not have the recognition (as an author) that she deserves. She overcame many obstacles during her lifetime, and her achievements as a writer and lecturer are underappreciated. I think I wanted to help bring her the recognition that I feel she deserves.

Chapter 16: What has marked the key difference between being an interested reader of Armstrong’s “fragment of an autobiography” and sitting down with the text as an editor?

Behrend: I had to work sentence by sentence, word by word. A lot of the time, I felt that I was missing the flow of the story, but it had to be done to identify places where she made errors or misspoke. Editing the handwritten Part 2 was especially difficult. Her great-grandson had transcribed it and sent me the file; I also had a digital copy of the original. Comparing the transcribed copy to her original manuscript was very tedious. Mrs. Armstrong’s handwriting is quite unique and all over the place; there were many pages where she had marked through words, or even whole sections, and written changes in between the lines or in the margins. Her great-grandson has never lived in Knoxville, or even Tennessee, and many of the names of places, plus the personal names of figures in local history, were unfamiliar to him, resulting in discrepancies in the transcription which needed correcting. Also, as mentioned elsewhere, I was always on the lookout for people, places, events, etc., in her story that might need explaining or elaborating on.

Behrend: I had to work sentence by sentence, word by word. A lot of the time, I felt that I was missing the flow of the story, but it had to be done to identify places where she made errors or misspoke. Editing the handwritten Part 2 was especially difficult. Her great-grandson had transcribed it and sent me the file; I also had a digital copy of the original. Comparing the transcribed copy to her original manuscript was very tedious. Mrs. Armstrong’s handwriting is quite unique and all over the place; there were many pages where she had marked through words, or even whole sections, and written changes in between the lines or in the margins. Her great-grandson has never lived in Knoxville, or even Tennessee, and many of the names of places, plus the personal names of figures in local history, were unfamiliar to him, resulting in discrepancies in the transcription which needed correcting. Also, as mentioned elsewhere, I was always on the lookout for people, places, events, etc., in her story that might need explaining or elaborating on.

Chapter 16: Even though Armstrong started writing her memoir in her late 70s, she’s a master at detail and portraying specific sorts of relationships — the results of divorce or youthful daydreaming. There’s a transfixing musicality and rhythm to this storytelling. You write, “Armstrong was such a good writer that I’ve made very few changes to her text,” yet you also describe her memoir as “really more a reminiscence, rambling and episodic, lapsing into flashbacks and stream of consciousness at times.” How did you shape the manuscript?

Behrend: I did not make changes in her story or rearrange any of it. Because of its length, there had to be cuts, but I tried to make them as seamless as possible. In a few places I cut material because I felt it was in the best interest of everyone concerned. Otherwise, I left Mrs. Armstrong’s story the way she told it but tried to fill in any gaps or questions that might arise by writing annotations to explain and provide context for her story at that point. I did clean up some of her punctuation and corrected, or noted, some misspellings (especially in proper names).

Chapter 16: You introduce Armstrong’s autobiography by saying both that it offers a vivid picture of Knoxville near the end of the 19th century and positing that you don’t claim it to be “in essence a factual work.” How are these two statements reconciled, each able to be true?

Behrend: It was Anne Armstrong herself who said (in the author’s preface), “… I do not claim this to be in essence a factual work.” She goes on to state that her aim in writing a memoir was to show what it was like to be growing up in Knoxville during the 1880s and 1890s. In my editorial note, I reminded readers that she might have “fabricated or embellished” some of the stories she was recounting.

Chapter 16: Editing this book has required a prodigious amount of research. How did you codify so much material?

Behrend: Every time I came across a name, place name, date, event, etc., in the manuscript, I made a note of it so that I could go back and verify it. Many times, it took a lot of digging to find the right, or enough, sources for me to feel confident that I had a clear understanding of the facts. Then, I composed annotations that would provide background information (if needed) and citations for my sources. As a librarian, these are things I had learned how to do.

I spent a lot of time in McClung Historical Collection at the East Tennessee History Center in Knoxville and checked a lot of books out of both the Knox County Public Library and the University of Tennessee’s Hodges Library. I also used a lot of online library resources, databases, newspaper archives, etc. Online resources were especially important because some of my research was done during the COVID pandemic. While they were closed because of COVID, the Knox County Public Library made many databases available to users that were normally limited to onsite use only. And the UT Special Collections library scanned and emailed documents, articles, etc., to me during times when there was no access to the building.

Chapter 16: What’s your favorite line in the book?

Behrend: There are two:

One is when she marries Bob Armstrong and, as they are leaving the church, her son “whispered shyly in [her] ear, ‘Mother, I call it sacred ground where first they trod” — for now his beloved ‘Uncle Bob’ had become ‘Father.’”

The other is at the end of her story when she and her husband return to Knoxville for a visit 30 years after she had left her adopted hometown. He tells her that Knoxville was not ever as she remembered it, and she replies: “But, Bob,” I protested, my heart heavy, “Knoxville was my first great love, and I don’t suppose I shall ever quite get over it.”

Sarah Norris has written about books and culture for The New Yorker, The San Francisco Chronicle, Village Voice, and others. After many years away, she’s back in her hometown of Nashville.