Resisting a Truce with the Unknown

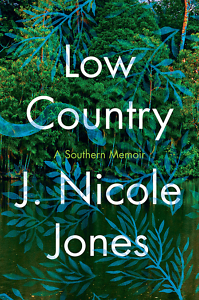

J. Nicole Jones conjures her South Carolina family’s storied past in Low Country

The opening lines of Low Country, a powerful memoir by part-time Nashvillian J. Nicole Jones, reflect a deeply personal tension between the familiar tropes of a Southern Gothic tale and the drive to challenge that tradition. “Once down in the low country I saw the ghost of a woman I knew well,” Jones begins. “Not the cool silver specters observed by men that portend danger and violent endings, but a beauty who basked in wide strands of sunshine and predicted nothing but herself.”

Richly detailed and atmospheric, Low Country tells the multi-generational story of Jones’ family but does so by hybridizing that narrative with an ecosystem of history, folklore, and ghost stories long associated with South Carolina’s swamps, beaches, and pine forests. Her father’s family built an empire in Myrtle Beach comprised of motels, golf courses, restaurants, and “other assorted tourist traps.” Designed to draw tourist dollars to the shore, the Jones empire drew in more than any of them bargained for.

Jones’ numerous male forebears succumb to addiction, philandering, and possible entanglements with organized crime. But her family’s legacy of physical abuse, embodied in the many cruelties inflicted by her paternal grandfather, is what haunts Jones the most, and she writes about these experiences with candor and insight.

“The first time I saw Granddaddy slap Nana across the face, at four or five, I knew that I hated him,” Jones writes, “but did not yet know how this baptismal spark of anger bonded us, how it would make me like him … As passively as catching a cold, his disease was activated in my blood, which was partly his after all.”

Surrounded by brothers and male cousins, Jones begins to notice how differently she is treated as the only girl-child, and this difference fuels her conviction to forge her own path. But doing so proves more difficult than she expects. “A different shade of anger, the silent resentment that smolders in all women, was beginning to rival the fear and hatred I saw in Granddaddy. At least the anger in men counted.”

Jones resolves that her life must not follow the constrained, long-suffering path expected of her. Referring to the Southern tradition of painting porch ceilings “haint blue” to keep troubled spirits from crossing the threshold, Jones writes, “If I could have painted the roof of my mouth that lovely shade of haint blue to scare away the ghosts of women I did not want to be, the women I came from, I would have licked clean the brush.”

Jones resolves that her life must not follow the constrained, long-suffering path expected of her. Referring to the Southern tradition of painting porch ceilings “haint blue” to keep troubled spirits from crossing the threshold, Jones writes, “If I could have painted the roof of my mouth that lovely shade of haint blue to scare away the ghosts of women I did not want to be, the women I came from, I would have licked clean the brush.”

Early in the book, Jones owns up to her ambivalence toward her heritage, as well as her pull toward it.

After leaving the South, determined not to return, the stories call her back. In part, her fraught relationship to her origins mimics her description of locals offering ghostly stories to explain flashes of bioluminescent light emanating from the swamp. This lore points to “a region in search of reasons for the violence of its past, not ready to give up its ghosts and the guilt that brings them ever back to life.”

Adult insights push against her childhood memories, undoing some things while confirming others. One potent recurring memory revolves around her father writing country songs and dreaming of future stardom “under the sacred porcelain gaze of an Elvis Presley bust looking down from his bookshelf on high.” Years later, she discovers that the bust was “a bourbon decanter and not a golden calf. That we had been praying to the alcohol all along explained a few things.”

Jones oscillates between loving compassion for those who shaped her (like her restless songwriter father and her self-effacing, fascinating grandmother) and toughminded inquiry into the unanswered questions that haunt the received family narrative. Jones argues, “What is tradition if not a truce with the unknown, of which there isn’t as much as there used to be.” But these pages contain the recognition that, in a story this complicated, there can be no fixed and final understanding.

Resisting more linear methods of storytelling, which she associates with patriarchal gatekeeping, Jones seeks another shape for her story: “Here we chuck out Aristotle in favor of the forms of women who tell stories shaped like themselves that history made a point of forgetting.”

Jones finds her form by swirling together the world of her family’s lore with the legend-heavy history of her South Carolina homeland, never resting too comfortably from any fixed position. Animated by equal measures of rigorous self-awareness and ample respect for mystery, Low Country becomes an engrossing, harrowing read.

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Mississippi Review, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Bayou Magazine Online, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.