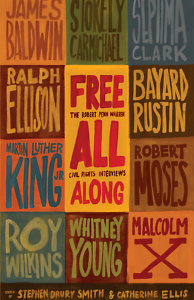

Revisiting the Movement

Robert Penn Warren’s 1964 interviews with civil-rights activists get an updated look

The source material for Free All Along, an edited collection of interviews conducted by the novelist and poet Robert Penn Warren, one of the Vanderbilt University students who launched the Fugitive movement of the 1920s, stands or falls according to its form and its audience. Both have varied in the decades since Warren conducted the interviews in 1964. Whenever the material appears anew, it’s fair to ask, “Why this book, in this particular form, right now?”

Beyond question, the interviews in this collection have intrinsic historical value. In 1964, arguably the high point of the Southern civil-rights movement, Warren spent several months recording his conversations with a number of people in and around the civil-rights movement in the South. His subjects included world-historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X; intellectuals like sociologist Kenneth B. Clark and novelists Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin; and many civil-rights activists, from establishment types like Roy Wilkins and Whitney M. Young Jr. to grassroots figures like Robert Moses, Charles Evers, Aaron Henry, Septima Clark, and Ruth Turner Perot.

Beyond question, the interviews in this collection have intrinsic historical value. In 1964, arguably the high point of the Southern civil-rights movement, Warren spent several months recording his conversations with a number of people in and around the civil-rights movement in the South. His subjects included world-historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X; intellectuals like sociologist Kenneth B. Clark and novelists Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin; and many civil-rights activists, from establishment types like Roy Wilkins and Whitney M. Young Jr. to grassroots figures like Robert Moses, Charles Evers, Aaron Henry, Septima Clark, and Ruth Turner Perot.

Warren compiled and edited these conversations, which make up the core of his impressionistic, searchingly honest book, Who Speaks for the Negro?. The book was published in 1965 but went out of print for a number of years before being reissued by Yale University Press on the event of its fiftieth anniversary. Who Speaks for the Negro? featured many of Warren’s own impressions of the era as it unfolded, and he edited the interviews carefully to fit the form of his thinking. The interviews were available to the public in no other form until 2012, when the Robert Penn Warren Center at Vanderbilt debuted a dynamic, very useful website featuring the original interviews, in unedited form, as both audio and written transcripts.

Free All Along provides yet another venue for readers interested in Warren’s interviews, this time edited for length and repetition and with a fair number of interviews omitted. This particular collection is a tidy document with helpful introductions, and it should introduce Warren’s interviews to a readership that reaches beyond researchers and specialists. The book could certainly serve as a companion to the Warren Center website and to Warren’s book, as well—an opening that invites readers to explore those earlier forms.

But it could do more than that, too, which brings us again to the question: “Why this book, and why now?” Obviously, lingering racism, economic inequality, and mass incarceration, among other issues, occasion a glance back in time. We live in a season of activism, so it makes sense to explore understandings of activism in the past.

Contemporary readers might be surprised at what they find. While the world revealed in this book seems very different from our own, some problems remain stubbornly unresolved. With his interviewees, Warren sought a full portrait of the movement, considering questions of identity, strategy, tactics, and history, lining up differences in status, position, and definition. The discussion ranged all over the place, from the local to the global, but Warren asked some questions consistently. He puzzled over the phrase “Freedom Now” with many of his subjects, considered debates over nonviolence within the movement, wondered whether the events then unfolding ought to be called a “revolution” or not, and so on.

Warren was at his best with literary artists, and Smith and Ellis rightly mention that “critics and historians have singled out the interviews with two fellow writers—James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison—as especially candid and powerful.” The interview with Kenneth B. Clark was easily the most bracing and combative, which might be surprising given that Malcolm X appears in the book. In preparing to interview writers, Warren had a body of their own work from which to draw, so he could be more direct in his questioning. He didn’t need information, so he could immediately ask for interpretation.

In his interviews with activists, however, Warren tended to privilege testimony over analysis. Students of the movement have probably heard some of the resulting stories before, but the format of this book might inspire a different reading. Thinking along with Warren and his subjects, we might recall something obvious yet essential. The history of the movement had yet to be written when Warren made these recordings, and, as it turns out, 1964 was a critical, turning-point year in American history.

A book like Free All Along is necessary because it sharpens the reader’s historical consciousness. Immerse yourself in it. Read it from beginning to end. Allow yourself to inhabit the world of the people in its pages. Think about what they could not have known, the events that transpired only a few short years later. Then imagine our present world in the same frame of mind, considering the future that lies before us. From that critical vantage point, Free All Along might just become essential rather than merely useful.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and thought. He is also a regular blogger for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).