Riffing on the River

In Lee Sandlin’s eclectic new history, it’s a treat to beat your feet in the Mississippi mud

Among the many peculiar beliefs, practices, and entertainments along the Mississippi in the early nineteenth century was a ritual sport known as “shout-boasting.” As essayist Lee Sandlin explains in Wicked River: The Mississippi When it Last Ran Wild, this form of competitive elocution was usually practiced from atop a keelboat or raft of goods headed downriver. The point was for the shout-boasters “to make up surreally violent claims about themselves and then dare to fight anybody who challenged them.” Sandlin provides an example: “Whoo-oop! I’m the original old iron-jawed, brass-mounted, copper-bellied corpse-maker from the wilds of Arkansaw! Look at me! I’m the man they call Sudden Death and General Desolation! Sired by a hurricane, dam’d by an earthquake, half-brother to the cholera, nearly related to the small-pox on the mother’s side! Look at me! I take nineteen alligators and a bar’l of whiskey for breakfast when I’m in robust health, and a bushel of rattle-snakes and a dead body when I’m ailing!”

This passage goes on for considerable length, and for two reasons it is emblematic of Sandlin’s wickedly funny new history of the great river. First, the Mississippi itself becomes the main character of Sandlin’s musings, and a violent, profane, drunken, calamitous, hypocritical, and wholly American character it is—perhaps even the American character, in an archetypal sense of the cowboy. But even more important, the passage itself, which Sandlin’s careful research of period literature supports as a wholly accurate example, was written by Mark Twain. As Sandlin points out in his prologue, at the time Twain’s great novel—The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, probably the single most influential work about the character of life on the Mississippi—was written, it was already a nostalgic recollection of a way of life that had vanished more than two decades earlier.

The “wild” river of Sandlin’s subtitle was well-tamed after the Civil War, with dams, locks, and and levees to control its value as the main corridor of commerce in the nation; and with prim, conservative cities that had grown up where once there were lawless, raucous settlements. It is this earlier, rarin’-for-a-fight stream, as it existed from about 1810 until 1865, that Sandlin sets out to describe. His course winds and meanders like the river itself, through the “Great Shakes,” the earthquakes of 1811 and 1812, which remain the most powerful ever recorded in the United States; past the rise of the “Camp Meeting,” a weeks-long religious retreat that could number in the thousands, culminating in a near riot that was often half orgy; and into the great slave revolt plot of 1835, a wholly fictional event that nonetheless led to hundreds of actual lynchings and other acts of lawlessness. In most cases, readers also learn how the population itself, much like the land along the New Madrid fault, had calmed by the time Twain began writing about Huck Finn. (One chapter of Wicked River ends: “The religious authorities that dominated American churches later in the century regarded the boredom of the new camp meetings as one of their greatest moral triumphs.”)

The “wild” river of Sandlin’s subtitle was well-tamed after the Civil War, with dams, locks, and and levees to control its value as the main corridor of commerce in the nation; and with prim, conservative cities that had grown up where once there were lawless, raucous settlements. It is this earlier, rarin’-for-a-fight stream, as it existed from about 1810 until 1865, that Sandlin sets out to describe. His course winds and meanders like the river itself, through the “Great Shakes,” the earthquakes of 1811 and 1812, which remain the most powerful ever recorded in the United States; past the rise of the “Camp Meeting,” a weeks-long religious retreat that could number in the thousands, culminating in a near riot that was often half orgy; and into the great slave revolt plot of 1835, a wholly fictional event that nonetheless led to hundreds of actual lynchings and other acts of lawlessness. In most cases, readers also learn how the population itself, much like the land along the New Madrid fault, had calmed by the time Twain began writing about Huck Finn. (One chapter of Wicked River ends: “The religious authorities that dominated American churches later in the century regarded the boredom of the new camp meetings as one of their greatest moral triumphs.”)

Around some bends are characters quirky enough to warrant extended biographies, such as Timothy Flint, a “stiff-necked, querulous and perpetually aggrieved” Puritan missionary from Massachusetts, who is an utter failure as minister to several churches up and down the river, often barely escaping death from disease and river disasters as he roams in search of religious work. “A college friend observed of him that there were two striking aspects to his character,” Sandlin writes. “He was useless at social intercourse and he was entirely ignorant of human nature.” Despite these traits, Flint later falls into the profession of author, becoming during his lifetime one of the most widely known chroniclers of travel and life on the Mississippi.

Then there is William Johnson, a free African American man who was a prominent barber and local investor in Natchez. He kept scrupulous diaries from about 1830 until his murder in 1851. Many of the entries describe duels, fistfights, and gambling, interspersed with the mundane details of commerce. A typical entry reads, “I rode out today to see the balloon ascend, but the man did not attempt to put it up at all, and told them that they would put it up tomorrow. A mob was soon raised and they tore it all to pieces, destroying everything as they went.” Two days after Johnson’s final entry (“Business is very dull indeed but nothing like as dull as was yesterday”) Johnson himself meets an end not unlike the balloon’s, in all probability at the hand of a business rival, a white man who felt bested by Johnson in a timber deal.

Then there is William Johnson, a free African American man who was a prominent barber and local investor in Natchez. He kept scrupulous diaries from about 1830 until his murder in 1851. Many of the entries describe duels, fistfights, and gambling, interspersed with the mundane details of commerce. A typical entry reads, “I rode out today to see the balloon ascend, but the man did not attempt to put it up at all, and told them that they would put it up tomorrow. A mob was soon raised and they tore it all to pieces, destroying everything as they went.” Two days after Johnson’s final entry (“Business is very dull indeed but nothing like as dull as was yesterday”) Johnson himself meets an end not unlike the balloon’s, in all probability at the hand of a business rival, a white man who felt bested by Johnson in a timber deal.

The outcome of the resultant legal proceedings is not hard to guess, but in the telling of it, Sandlin reveals a world that, for all its frequent ignorance, cruelty, and racism, remains fiercely independent. It is a world that clearly shaped many aspects—for better or worse—of what is now regarded as the American character. The earnest fervor of a Tea Party crowd and the wry humor displayed by those attending the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear would have been equally familiar (if perhaps more likely to end in casual violence) in any river town of 1840. Sandlin describes Abraham Lincoln, who in his youth had ferried a raft of goods down the river, as possessing “this kind of submerged taste for the manic” that marked river people.

Appropriately, Wicked River culminates with the wreck, in 1865, of the Sultana, a massive steamboat which first ventured south from Illinois to carry the news of Lincoln’s assassination to cities along the river to New Orleans. Later, at Vicksburg, the boat was overloaded with Yankee soldiers recently released from Confederate prisons, and narrowly avoided sinking several times before a boiler burst near Memphis, dooming many of the passengers, along with a massive pet alligator. The sinking of the Sultana ultimately took more lives than that of the Titanic. The wreck itself settled to the bottom in a channel near the Arkansas shore, about seven miles north of Memphis. “Over the next few years, the river shifted course, and the channel was emptied of its current,” Sandlin writes of the boat, in a passage that grows into a moving metaphor of the wild Mississippi. “The great banks caved in, and the bottom was covered over by wash after wash of mud and silt deposited from upstream. Eventually the last traces of the channel and its islets were swallowed up. The soil grew rooted with meadow grasses and wildflowers and trees; then the land was cleared and cultivated, and the Sultana rested deep beneath the soybean fields of Arkansas.”

The fate of the steamboat, and the manner of life that ended with it, will rest deep beneath the reader of this marvelous history.

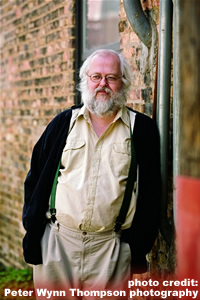

Lee Sandlin will discuss Wicked River at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on November 9 at 6 p.m.