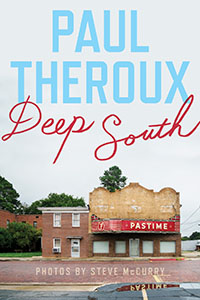

Road Master

Paul Theroux turns his keen traveler’s eye upon southern states and the state of all things Southern

Forty years have passed since The Great Railway Bazaar cemented Paul Theroux’s reputation as one of America’s greatest travel writers. In a career that includes—so far—a remarkable fifty-one books, the seventy-four-year-old writer has published much more fiction than nonfiction, including such acclaimed novels as The Mosquito Coast and Half Moon Street. But it may be his travel writing that claims the most devoted fans. Theroux has a knack for meeting interesting people and describing them with verve and irony in a way that somehow captures the essence of the place in which he finds them. It should therefore come as no surprise that Theroux, who lives in New England, has now turned his wit upon a land brimming with character and contradiction: the American South.

Deep South follows Theroux’s peripatetic rambles down various southern byways during four seasons, with each of the book’s four sections capturing idiosyncratic regions and sensibilities—and often touching on issues in which the South has been the focus of national attention. In advance of his appearance at the Southern Festival of books in Nashville, Theroux recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Deep South follows Theroux’s peripatetic rambles down various southern byways during four seasons, with each of the book’s four sections capturing idiosyncratic regions and sensibilities—and often touching on issues in which the South has been the focus of national attention. In advance of his appearance at the Southern Festival of books in Nashville, Theroux recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Many of the narrative sections of Deep South are labeled not by place but by an individual’s name. Of all the people you met, did anyone stand out as the most memorable?

Paul Theroux: The Deep South is full of unsung heroes. Idealistic and hardworking people who have striven to make a difference. I met them everywhere I went and I hate to single out just one, but since you asked I would mention an older gentleman, the Reverend Eugene Lyles, who in the 1960s in Greensboro, Alabama, struggled to get a bank loan to build a modest building to house his barber shop and his soul food restaurant, both of which have been successful and welcoming. He also preaches in a local church. And he was instrumental in arranging for Martin Luther King Jr. to speak in the town—a dangerous activity in those years. I should also add that he was hospitable and candid to me, an unimpressive stranger with lots of questions.

Chapter 16: Much like your fiction, your travel writing is punctuated by dialogue that reveals a depth of character and culture. How do you manage to capture long, engaging exchanges while simultaneously taking part in them (in one case, while shooting a rifle)?

Theroux: This challenge lies at the heart of the travel narrative and depends on memory. It is a skill I have worked at for forty years. I do not use a tape recorder, but at the end of the day I rack my brain to reproduce the dialogue I heard all day and do not go to bed until I have set it down in my notebook as accurately as I can.

Chapter 16: You embarked on your Southern journey during the 2012 presidential race. Given the insights you gleaned from that trip, what do think of the current presidential race as it’s playing out in the South?

Theroux: At the moment the presidential race for 2016 is a set of sideshows, many of them played as farce, almost in defiance of serious politics and probably to mock the process. At some point, probably next year, the real contenders will emerge. I don’t think we have seen them yet.

Chapter 16: Among Deep South’s rich descriptions of place and people are a few more philosophic meditations, such as your discussion of the history and use of the n-word. How have early readers responded to that essay?

Theroux: No fuss yet that I have heard. May I also say that the expression “the n-word” sounds to me like baby talk. I call it “the taboo word” because of course it is used freely by African Americans and represents a taboo to whites. I used this word, quoting a man in Monroeville in a piece I wrote for Smithsonian, and as it was a neutral—not hostile—usage, no one became apoplectic.

Theroux: No fuss yet that I have heard. May I also say that the expression “the n-word” sounds to me like baby talk. I call it “the taboo word” because of course it is used freely by African Americans and represents a taboo to whites. I used this word, quoting a man in Monroeville in a piece I wrote for Smithsonian, and as it was a neutral—not hostile—usage, no one became apoplectic.

Chapter 16: At a Mississippi gun show you attended, people saw assault weapons as a solution to—rather than potential precursor of—mass shootings in America. What do you think of recent shootings in light of your experience there?

Theroux: I don’t think gun owners in Mississippi or elsewhere think of assault weapons as a solution to violence. The ones I met felt that gun regulation was yet another manifestation of the federal government trying to run their lives. The recent shootings have been lamentable, but each has had a different aspect. Strict background checks might have prevented some of them.

Chapter 16: You were guest editor of The Best American Travel Writing 2014. What impression of the state of the genre—or of travel itself—did that experience leave you with?

Theroux: A very good question, and a timely one. Travel is no longer about a vacation, or a wine trip down the Rhine, or Mr. and Mrs. Traveler reporting on their high-priced safari. Travel writing now penetrates deeper into countries near and far, involves different risks and challenges (refugees, poverty, civil war, crisis) and is less narcissistic and sybaritic—no longer the elephant ride or the spa experience.

Chapter 16: What was your most memorable meal in the South?

Theroux: Sunday lunch, after church, to which I was invited on the spur of the moment by Mr. and Mrs. H.B. Williams in Monroeville, Alabama—me, a perfect stranger from the distant North, to share chicken, mac and cheese, sweet potatoes, and pie. I recall the peacefulness of it, the good humor, the great food, the hospitality. It seemed to characterize all the hospitality and candor I met in the South.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a forthcoming textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.