Sad Song

Cyril E. Vetter riffs on the troubled times of Louisiana bluesman Charles “Butch” Hornsby

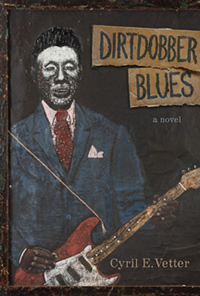

In any history of the American music scene of the late sixties and early seventies, the name of Louisiana songwriter Charles “Butch” Hornsby, who died of leukemia in 2004, is unlikely to warrant much more than an asterisk. It’s not that he lacked talent: Hornsby’s blues-influenced Southern rock vibrates with both energy and lyrical reserve. His is a unique sound that surges from decades-old recordings made in crowded juke joints—an angry young white man, his voice infused with the dignity of a spiritual, delivers painful lyrics in a cadence that summons images of tent revivals and snake handling. But Hornsby is one of those musicians known more by legend than actual audience, the sort whose name is reverently dropped by seasoned old-timers, music trivia buffs, and virtually no one else. His path to obscurity, as is often the case, was forged entirely by his own bad choices. In Dirtdobber Blues, Cyril E. Vetter, Hornsby’s long-time friend and some-time producer, has created a fitting tribute, a short roman à clef that is part novel, part biography, part photography, part painting, and part song.

The song part comes in the form of a CD of fourteen of Hornsby’s songs included with the print version of the book (the songs are embedded within the electronic edition), most of them recent recordings by Hornsby contemporaries Duke Bardwell and Will Kimbrough. Masterpieces like “Rock Bottom on Romaine” and Hornsby’s regional hit single, “Suddenly Single,” are interspersed with modern renditions, such as the book’s title song. “If you listen to the music while reading the book,” Vetter writes in his preface, “I believe it will enhance the experience.” This is excellent advice, for two reasons. First, most readers are unlikely to be familiar with Hornsby’s music, which truly captures a time and place in American history. Second, the music is good enough to make readers put up with Hornsby the character, who emerges in the first half of the book as, according to Vetter himself, “a manic SOB”: drunken, boorish, and self-destructive to the point that he seems intent on bringing even his loyal and talented friends to the brink of ruin.

Vetter recently told a reporter from The Orange County Register that some of his wilder stories of Hornsby’s behavior were not fictionalized but happened more or less exactly as the book lays them out. These episodes include blowing a month’s pay on a cab ride from Los Angeles to Fresno in order to rescue a friend’s guitar from a pawn shop, and giving Vetter himself a $15,000 album advance for safekeeping, only to get drunk later and attempt to steal it back. Chapters of impulsive and sometimes dangerous behavior are interspersed with songs, printed lyrics, and even sheet music, old photographs, and the folk-art Hornsby created later in life. Vetter has a good ear for dialog (likely the most fictionalized part of Dirtdobber Blues), but most of the writing is sparse, the scenes fleeting—more blues riff than detailed narrative. As straight prose, it would be an all-too-familiar and depressing story, without much else to recommend it, but the book’s media extras imbue it with the feel of performance art, or perhaps a highly personal and eclectic documentary film.

Vetter recently told a reporter from The Orange County Register that some of his wilder stories of Hornsby’s behavior were not fictionalized but happened more or less exactly as the book lays them out. These episodes include blowing a month’s pay on a cab ride from Los Angeles to Fresno in order to rescue a friend’s guitar from a pawn shop, and giving Vetter himself a $15,000 album advance for safekeeping, only to get drunk later and attempt to steal it back. Chapters of impulsive and sometimes dangerous behavior are interspersed with songs, printed lyrics, and even sheet music, old photographs, and the folk-art Hornsby created later in life. Vetter has a good ear for dialog (likely the most fictionalized part of Dirtdobber Blues), but most of the writing is sparse, the scenes fleeting—more blues riff than detailed narrative. As straight prose, it would be an all-too-familiar and depressing story, without much else to recommend it, but the book’s media extras imbue it with the feel of performance art, or perhaps a highly personal and eclectic documentary film.

The song arrangement chronicles the promise and ultimate demise of Hornsby’s recording career. The printed lyrics follow an artist on a self-destructive path that nevertheless leads him to poetic insights. None may be more poignant than these from Hornsby’s song “I Have Seen the Universe,” printed midway through the book, as the musician is set to make it big with a Los Angeles recording contract—if not for the fact that a criminal scandal is about to wreck all deals of the A&R man who signed him:

Insane actors and stars in ignition,

Insane actors and stars in ignition,

I know artists who don’t know recognition.

Living with the rats and roaches,

Estes tardes, buenos noches.

I have seen the universe,

It looks like home, it looks like home.

Through his friend Vetter, Hornsby’s album is eventually released but not promoted, and he begins years of live performances, living in Baton Rouge on the edge of fame, continually pushing away those close to him. He drifts to Nashville for a second shot at recording, but instead of a hit manages to find a wife and partner. After his music career finally crashes, Hornsby finds redemption, of sorts, through running a Nashville lawn service, through his family, through creating visual art—collages of found objects scavenged from the abandoned homes of sharecroppers and primitive paintings of tormented bluesmen, much of the work reproduced in Dirtdobber Blues—and through an unlikely conversion by the television preacher Jimmy Swaggart, pre-Baton-Rouge-hooker-tearful-confession.

Like all blues ballads, Butch Hornsby’s story is a tragedy broken by darkly comic, shining moments, and the hero and the villain are one and the same. In Dirtdobber Blues, Cyril Vetter has found an odd but ultimately appropriate and satisfying format to honor the man and his music.

Cyril E. Vetter will discuss Dirtdobber Blues on March 8 at 6:30 p.m. at Parnassus Books in Nashville.