Searching for the U.S.S. Flagg

What was my pandemic nostalgia really about?

When I was a kid, I would plop my scrawny body down on the living room carpet after school to watch G.I. Joe: Real American Hero. During commercial breaks, I salivated over the latest G.I. Joe toys. My mouth dropped open the first time I saw the U.S.S. Flagg, an aircraft carrier that stretched over 7 feet long and seemed to have come out of a fantasy. Covered with radars, cables, and missiles, the imaginary options it offered were endless. I envisioned myself posing my G.I. Joe action figures on the control tower and, like the kid in the commercial, holding the small microphone and shouting: “GET READY TO LAUNCH!”

When Hasbro released the U.S.S. Flagg in 1985, it was the largest G.I. Joe playset ever made. Most boys I knew had G.I. Joe action figures and playsets, but no one in my orbit had the Flagg. The price tag put it out of reach, leaving us to daydream about it, hoping it would magically appear on Christmas morning. But it didn’t for most boys.

The first time I spotted the Flagg on a shelf in the toy aisle, I stood in awe of the massive box. The humming fluorescent lights reflected off the glossy cardboard. On the front, a massive ship cut through white-capped ocean waves with an explosion of red and orange lighting up the dark sky. Engines roared and missiles blasted off in my imagination as I landed a jet between white stickers marking the runway. I don’t remember how long the battle raged in my mind, but I do remember my mother’s voice.

“What did you find?” she asked.

My eyes directed her to the top shelf.

“Oh, don’t even think about it,” she said.

“Why not?”

“It costs $100.”

A lump formed in my throat and my shoulders drooped.

“I promise I’ll never ask for a G.I. Joe toy again.”

“What else did you put on your Christmas list?”

I looked away and didn’t answer, pouting all the way to the parking lot. All I could think about was the giant battleship.

***

I hadn’t thought about the U.S.S. Flagg in years until, early in the pandemic, a picture of it appeared in my Facebook newsfeed. The image of the toy battleship (better known as the G.I. Joe aircraft carrier) caused a warm tingle to stir in my gut and rise to my chest.

As the weeks of shutdown wore on, I spent my quiet time after days of grueling childcare searching online for the U.S.S. Flagg. It became an evening ritual. Prices for a used one range from $200 for one with missing parts to $4,000 for one nearly complete. While scrolling through listings, I fell deep into the well of nostalgia. The narrow walls enclosed me in a warm bliss. I imagined playing with my sons — landing jets on the massive deck, posing action figures in the control tower, shouting orders into the microphone.

Lying in the bathtub one evening, recovering from a day spent with wild boys, my mind drifted into a hazy space somewhere between consciousness and sleep. On the screen in my mind, my 8-year-old self walked into a predawn living room, flipped on a light switch, and found a U.S.S. Flagg next to the Christmas tree. I ran to it and dropped to my knees and glided my palms over its deck, studying the stickers. I crawled around to the backside of the carrier and grabbed the built-in microphone and, like the kid in the commercial, shouted, “GET READY TO LAUNCH!” All morning I played with the U.S.S. Flagg, barely stopping to eat or use the bathroom. The smell of my mom’s sausage balls filled the room, while classic Christmas music played on cassette tape and parade floats passed by on television. The sounds of my grandparents’ voices slowly trickled into the room, along with aunts and uncles. I felt so free, safe, and unburdened. All there was to do was play and enjoy family and wallow in holiday warmth. The world’s darkness could not burst my childhood bubble.

Lying in the bathtub one evening, recovering from a day spent with wild boys, my mind drifted into a hazy space somewhere between consciousness and sleep. On the screen in my mind, my 8-year-old self walked into a predawn living room, flipped on a light switch, and found a U.S.S. Flagg next to the Christmas tree. I ran to it and dropped to my knees and glided my palms over its deck, studying the stickers. I crawled around to the backside of the carrier and grabbed the built-in microphone and, like the kid in the commercial, shouted, “GET READY TO LAUNCH!” All morning I played with the U.S.S. Flagg, barely stopping to eat or use the bathroom. The smell of my mom’s sausage balls filled the room, while classic Christmas music played on cassette tape and parade floats passed by on television. The sounds of my grandparents’ voices slowly trickled into the room, along with aunts and uncles. I felt so free, safe, and unburdened. All there was to do was play and enjoy family and wallow in holiday warmth. The world’s darkness could not burst my childhood bubble.

One night while scrolling for the Flagg, I went down a YouTube rabbit hole and, for half an hour, I watched grown men showing off their aircraft carriers, ones they purchased as adults. It felt like a strange Gen X therapy session.

I shared my research about the Flagg with dad friends in our group chat. We brainstormed ideas to raise enough cash to buy a used one. After accepting the reality that we couldn’t buy one in good condition, someone suggested we use his wife’s 3D printer to make our own. But this plan hit a dead end when we realized we didn’t know how to make stickers.

Before our plans fizzled out, I wondered where the 7-foot toy would fit in my modest home. One dad suggested it could double as a coffee table. Another friend sent me a picture of a U.S.S. Flagg he stumbled upon in a toy museum. It was missing a lot of parts and was roughed-up by the hands of many children. Whatever glory it once had was long gone. I wondered whether any U.S.S. Flagg I managed to buy would suffer the same fate.

A few nights later, sitting at the kitchen table, I promised myself I would stop scrolling for the Flagg. Enough was enough. But I still felt the inner tug-of-war — my nostalgic side nudging me to buy one and my pragmatic side reminding it was a ridiculous idea. I leaned back in my chair and stuffed my mouth with a handful of popcorn, wondering what it was I really wanted.

Two summers ago, my parents brought my childhood toys for my sons to play with and, at first, I felt the warm fuzziness of nostalgia. I enjoyed watching my boys play with the same toys I spent endless hours with. But this feeling quickly passed, and now I have little interest in them; they are piled along with other toys in our backyard.

Two summers ago, my parents brought my childhood toys for my sons to play with and, at first, I felt the warm fuzziness of nostalgia. I enjoyed watching my boys play with the same toys I spent endless hours with. But this feeling quickly passed, and now I have little interest in them; they are piled along with other toys in our backyard.

At age 41, I don’t need a 7-foot piece of plastic with cool stickers. The truth is I don’t care for G.I. Joe anymore. I’ve lost interest in the childhood world of fighting bad guys with fighter jets, bazookas, and aircraft carriers. Since becoming a father, I’ve become concerned with violence normalized by children’s shows and games. I’m not naïve enough to think I can shield my boys from it, but I’m not going to promote it.

I slammed the laptop shut and lay down on the couch, thinking about the nostalgic journey the U.S.S. Flagg took me on. It sunk me into the past but delivered me back to the current moment. For a long time, I’d understood my indulgence in nostalgia to be a hindrance to growth and progress. I saw it as a flaw, something to be avoided. I didn’t want to live my life stuck in the past. But then COVID brought a global crisis, and it seemed like everyone went on a nostalgic bender to find escape. Maybe, I thought, nostalgia served a purpose after all, a necessary emotion that helps us cope with rapid change.

I’ve come to believe nostalgia isn’t really about the past but the present. Nostalgia jerks us into the past to help us deal with the struggle we’re facing, reminding us of the best of people and places that formed us, allowing us to harness this energy to shape our lives now. We look back to find hope that life can be good again, hoping it will bring something better than what we have.

The human spirit must have something to cling to in dark times. I will always be the little boy looking up at the glossy box on the top shelf, but now, as an adult, I know it’s not the Flagg I want but to learn from the past so it can teach me how to live more fully today.

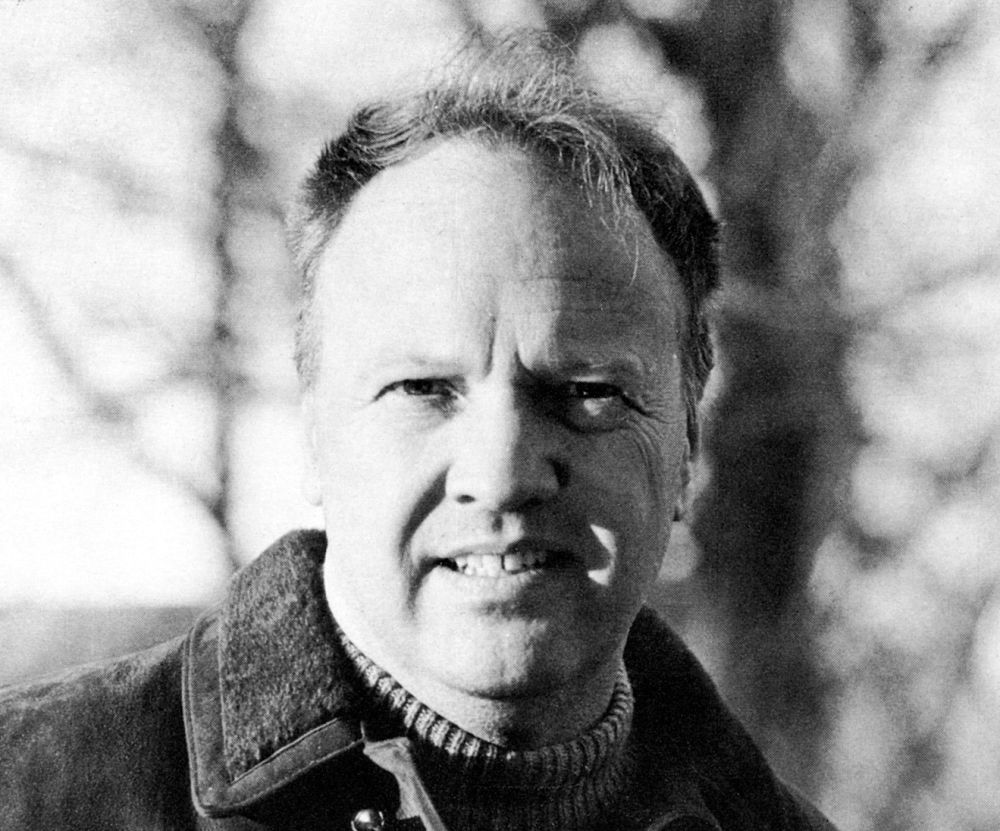

Copyright (c) 2022 by Billy Kilgore. All rights reserved. Billy Kilgore is a writer, at-home dad, and ordained pastor. He lives with his wife and two sons in Nashville. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post‘s “On Parenting” column, Narratively, Scary Mommy, and Fatherly. He is a graduate of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.