Seeing in the Dark

John Egerton considers a new memoir by a blind man—and the whole future of book publishing

The first time I laid eyes on David Meador, he walked into a bookstore where I was waiting in a small crowd for a speaker to address the perilous state of the book industry. Though he soon melted into the little literary redoubt with the rest of us hand-wringers, I kept glancing over at this tall, slender man. His face seemed frozen in a shy, self-conscious smile, the way most of us look when we walk into a room full of strangers. There was only one thing noticeably unusual about him: he was blind. As he was being guided to a waiting seat, he gently arced the point of his white cane across the carpet in front of him. Then he sat, alert and attentive, while the speaker held forth with news and analysis from the troubled field of publishing.

There was something riveting, even portentous, about the man with the white cane. A blind man in a bookstore! The symbolism of this tableau was arresting to me. Was he the herald of a new Dark Age, one without the abundant and ready availability of books, magazines, and newspapers? Will we all eventually have to feel our way along, as he does, to find open paths to words on paper?

There was something riveting, even portentous, about the man with the white cane. A blind man in a bookstore! The symbolism of this tableau was arresting to me. Was he the herald of a new Dark Age, one without the abundant and ready availability of books, magazines, and newspapers? Will we all eventually have to feel our way along, as he does, to find open paths to words on paper?

I won’t pretend to speak for anyone else who happened to be present when Roger Bishop spoke at BookMan/BookWoman that day. For all I know, my reaction was nothing but the winter solstice working its murky will on my sun-starved mind. It happens to me every year as darkness takes an ever-larger portion of each twenty-four-hour day. Finally, about three weeks into December, with Christmas looming, I reach the back of the cave and hunker down for a couple of months in a grumpy, semi-conscious funk. This time, having ventured out in search of a faint sign of hope—a stray ray from old Sol, a pastel crocus, an uptick in book sales—I had ended up in the small clutch of mourners lamenting the demise of our readerly-writerly way of life. The day fit my mood: a gray and gloomy Saturday afternoon in early January. The shops and sidewalks of Nashville’s Hillsboro Village were teeming with stir-crazy shoppers and searchers, desperados in flight from self-imposed hibernation. Those of us who had gravitated to the oval BOOKS sign above the mid-village shop were wedged into a cleared-out space between the front window and the narrow aisles that separated row on row of tall bookcases bearing uncounted thousands of previously read volumes waiting to be adopted.

Saralee and Larry Woods, the ever-smiling owners of BookMan/BookWoman, a fixture in the Village for over two decades, had emailed and otherwise beckoned their regular customers to what might be called a free counseling session with Roger Bishop, the gentle, self-effacing book guru whose vast knowledge of the print trade had made him indispensable to Davis-Kidd Booksellers, and before that to Zibart’s, another of the independent bookstores that for two centuries had given Nashville a well-deserved reputation as a great book town, a welcoming place for publishers and writers and readers.

We were feeling ourselves in need of counseling because the book business is in serious trouble. Zibart’s, and also Mills, the other prime twentieth-century bookstore in Nashville, had been gone for well over a decade—long enough that a majority of contemporary shoppers in the affluent Hillsboro Road corridor have no recollection of those great book merchants, whose history reached back to the heyday of the thriving downtown commercial district. Worse yet, only the middle-aged and older among us could remember when Karen Davis and Thelma Kidd opened their brash new independent bookstore in Green Hills thirty years ago. Now, lamentably, all of us were still reeling from the sudden death of Davis-Kidd in December, when the small and overreaching chain that had bought out Karen and Thelma’s enterprise in 1997 decided to pull the plug without so much as a farewell party (or a timely heads-up to the store’s pink-slipped employees). And, in our January torpor, we could only speculate about the dire straits of Borders, the nationwide bookstore chain, which a month later would seek bankruptcy protection to try to salvage some of its stores, including a big one on West End Avenue across from Centennial Park.

We were feeling ourselves in need of counseling because the book business is in serious trouble. Zibart’s, and also Mills, the other prime twentieth-century bookstore in Nashville, had been gone for well over a decade—long enough that a majority of contemporary shoppers in the affluent Hillsboro Road corridor have no recollection of those great book merchants, whose history reached back to the heyday of the thriving downtown commercial district. Worse yet, only the middle-aged and older among us could remember when Karen Davis and Thelma Kidd opened their brash new independent bookstore in Green Hills thirty years ago. Now, lamentably, all of us were still reeling from the sudden death of Davis-Kidd in December, when the small and overreaching chain that had bought out Karen and Thelma’s enterprise in 1997 decided to pull the plug without so much as a farewell party (or a timely heads-up to the store’s pink-slipped employees). And, in our January torpor, we could only speculate about the dire straits of Borders, the nationwide bookstore chain, which a month later would seek bankruptcy protection to try to salvage some of its stores, including a big one on West End Avenue across from Centennial Park.

The meeting area in BookMan/BookWoman is quite limited. In such a small space, an audience of two dozen or so can feel like hundreds, a throng. We strained to hear the soft-spoken Bishop as he tried to make sense of the electronic revolution that is changing the way humans communicate. The committed readers, writers, editors, and publishers among us who have always lived on a steady diet of offerings from the world of print were comforted, as always, by Roger’s supportive and reassuring manner. Still, I could feel my seasonal affective disorder smothering his calm bedside manner under a blanket of gloom and doom.

I glanced again at the blind man. He still wore the same alert countenance and the same smile that he had brought into the room; if he was our bearer of bad news, he gave no hint of it. After the program had ended, I saw him talking with Larry Woods, who called me over and introduced us, me as a journeyman freelancer and David Meador as a newly published author. “David needs a ride home,” Larry said. “Could you give him a lift?”

Before we had reached my car, the novice was subtly lighting up the gray day with cheerful antidotes to the old grouch’s pessimism. Soon we were talking shop. By the time we had reached his home, we were planning to meet again, and his insights would cause me to rethink my negative attitude about the decline and fall of the printed word.

My first book was published in 1970. If you count that as the last year of the sixties, I have been writing books—and getting them published—for five decades, half a century. When I started, there were still publishers in New York willing to give advances on manuscripts that were not likely to attract more than four or five thousand book buyers. I should know—I nursed a couple of those into print myself, and neither of them exceeded those minimal expectations. Still, the doors remained cracked open for me, and I was able to carve out a modest career as an independent journalist and author of nonfiction books set in this eccentric and enigmatic region in which we live. My forte, so to speak, was foretelling the imminent demise of the South—and all that kept me gainfully employed was its stubborn refusal to die.

Somewhere in the paper detritus that aggregates my checkered career as a wordsmith, I saved a few statistics on the book trade in America, circa 1970. The notes elude me now, but I remember some of the numbers, which in those days I cited frequently in speeches. This is the gist: about 40,000 new trade-book titles, fiction and nonfiction, were published that year. (My name was on one of them, called A Mind to Stay Here.) Twenty years later, in 1990, the number of new titles had doubled to 80,000 (out of an estimated 2 million manuscripts submitted to publishers!)—and close to 65,000 of the chosen were financial failures for both authors and publishers; they didn’t sell enough copies to cover expenses. Of the approximately 15,000 titles that “succeeded,” only about 200 earned for their authors as much as $100,000 over their lifetime. Even if that lifetime translates to just five years of the author’s career (say, one year for research, one for writing, one for steering through the production process, and two for sales), it works out to only twenty grand a year—call it ten dollars per hour. Think of it as the minimum wage of the literary upper echelon: those 200 out of two million writers of book manuscripts in 1990 who got book deals that eventually paid them the equivalent of ten bucks an hour for five years.

Somewhere in the paper detritus that aggregates my checkered career as a wordsmith, I saved a few statistics on the book trade in America, circa 1970. The notes elude me now, but I remember some of the numbers, which in those days I cited frequently in speeches. This is the gist: about 40,000 new trade-book titles, fiction and nonfiction, were published that year. (My name was on one of them, called A Mind to Stay Here.) Twenty years later, in 1990, the number of new titles had doubled to 80,000 (out of an estimated 2 million manuscripts submitted to publishers!)—and close to 65,000 of the chosen were financial failures for both authors and publishers; they didn’t sell enough copies to cover expenses. Of the approximately 15,000 titles that “succeeded,” only about 200 earned for their authors as much as $100,000 over their lifetime. Even if that lifetime translates to just five years of the author’s career (say, one year for research, one for writing, one for steering through the production process, and two for sales), it works out to only twenty grand a year—call it ten dollars per hour. Think of it as the minimum wage of the literary upper echelon: those 200 out of two million writers of book manuscripts in 1990 who got book deals that eventually paid them the equivalent of ten bucks an hour for five years.

If the numbers were that abysmal two decades ago, it seems impossible that they could have gotten worse. But they have. Nielsen BookScan, a company that tracks book sales, reported that of the 1.2 million discrete titles in print in 2004 (that’s fourteen times more than in the late 1940s), only 24,000—or 2 percent—had sales of 5,000 or more copies that year. If you were in that exclusive circle of “successful” authors, sales of 5,000 books probably rewarded you with $10,000 or less.

Numbers drive me to distraction. But before we all gorge on them and flee screaming for something more pleasant to read, please file away this conclusion: neither wars nor great economic depressions nor seemingly capricious natural calamities will stay a tiny fraction of the American populace from writing books; the absolute number who produce book-length manuscripts this year will predictably exceed two million, rising in step with the overall population. Perhaps 100,000 will be printed, 20,000 will barely break even, and a few hundred of them will take home a profit. You can get approximately the same odds at any casino in the country. In fact, that analogy is even more broadly persuasive: like gamblers, writers exist in a perpetual buyer’s market that never cants in their favor; both practices showcase just enough big-time winners to bring a critical mass of losers back to the table; writers and gamblers even share some of the same occupational diseases, from alcoholism to eye strain to hemorrhoids. (Not even gambling, however, has devised a torture as devious and sadistic as the publishing world’s “returns” policy, under which paper earnings can be converted into losses that continue to eternity.)

Now we find ourselves in the twenty-teens, and fortunes generated from Publishers Row, such as they are, continue to deteriorate. The carnage is strewn across the landscape: newspapers and magazines failing, book critics becoming an endangered species, independent bookstores falling left and right, even chain stores in trouble. People who used to write for a living are losing ground to bloggers and sundry other scribes who write for nothing—and all too often seem worth no more than that. Book publishers, with the same endless supply of manuscripts to pick from, keep on trolling for the big blockbuster that will make their year, all the while glancing nervously at the electronic wolves howling at the door. It is in this precarious environment that print-on-demand technology and new-age gadgetry from Amazon and Google and others have mounted a direct challenge, if not a lethal assault, that threatens the future productivity of words on the printed page.

In this doomsday scenario, Amazon looms as a terrifying Darth Vader figure. Every other character in the drama has reasons to fear Amazon—and reasons to court its favor, lest they be atomized. The corporation’s Kindle reader can make available a vast array of books, new and old, for a modest price; you can buy your Kindle for a mere 140 dollars, and fill it with titles dirt cheap—ten dollars or less, even free—with no shipping costs or sales tax added. (Never mind that your savings come from a rigid monopoly; only Amazon can feed books to your Kindle.) You can also buy deeply discounted print editions from the amazonian behemoth, again without sales taxes or other add-ons. The net result will almost surely help your wallet—and just as surely help to seal the fate of your local bookshop, not to mention shrink sales tax collections in your city and state. (Adding insult to injury, Amazon is now building a distribution center in Tennessee that appears to have been given a major pass by state officials to avoid even more taxes, based on the trickle-down economic theory that lower costs and fewer regulations at the top will yield more tax-paying workers at the bottom.)

In this doomsday scenario, Amazon looms as a terrifying Darth Vader figure. Every other character in the drama has reasons to fear Amazon—and reasons to court its favor, lest they be atomized. The corporation’s Kindle reader can make available a vast array of books, new and old, for a modest price; you can buy your Kindle for a mere 140 dollars, and fill it with titles dirt cheap—ten dollars or less, even free—with no shipping costs or sales tax added. (Never mind that your savings come from a rigid monopoly; only Amazon can feed books to your Kindle.) You can also buy deeply discounted print editions from the amazonian behemoth, again without sales taxes or other add-ons. The net result will almost surely help your wallet—and just as surely help to seal the fate of your local bookshop, not to mention shrink sales tax collections in your city and state. (Adding insult to injury, Amazon is now building a distribution center in Tennessee that appears to have been given a major pass by state officials to avoid even more taxes, based on the trickle-down economic theory that lower costs and fewer regulations at the top will yield more tax-paying workers at the bottom.)

And there is one more big electronic innovation in the book business that must be noted here: self-publishing. Vanity presses have existed for decades on the fringes of the book industry, but in the past decade or so they have ridden the technological wave to new prominence. In theory—and, broadly speaking, in fact— established publishing houses have created among book-buyers an expectation of superior vetting, editing, production, and marketing. Largely for those reasons, self-published books have never enjoyed the same exposure as works from traditional sources. Most book-review organs (including this website, Chapter 16) do not accept self-published works for review. Notwithstanding that, such volumes are now the fastest-growing segment of the industry—which is entirely in keeping with my earlier assertion that a steady fraction of the population will keep on writing books, come hell, high water, the cyber-revolution, or a new Dark Age.

But it is too simplistic, and demonstrably wrong-headed, to conclude that the established book-publishing houses have cornered the field on skilled authors, good books, or the buying power of readers. I could cite a dozen examples off the top of my head to support that assertion, but in the interest of conserving space I’ll only mention one that I just read about in The New York Times: in 2009, a guy named Matt Moore, a twenty-something Nashville musician, self-published a cookbook, Have Her Over for Dinner. Now, two years later, he is suddenly getting free and favorable exposure on NBC’s Today Show and in the Wall Street Journal, as well as in the Times. For reasons that may or may not be associated in any way with rejection letters from publishers, a growing number of self-published authors are finding ways to sell their wares, and help keep the printed word alive.

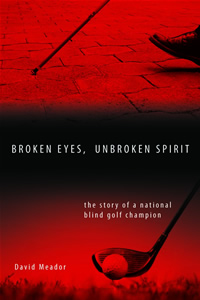

All of this brings me back around to David Meador. He was eighteen years old when his optic nerves were crushed in a car accident, leaving him totally and permanently blind. From there he went on to earn two college degrees, live and work in Chicago and Nashville, have a career as a life insurance agent, meet his responsibilities as a husband-father-grandfather, survive cancer (twice), and win the National Blind Golfers Association championship. Now, at sixty-two, he has written and self-published Broken Eyes, Unbroken Spirit, his memoir of almost half a century of seeing in the dark. None of these accomplishments would have been possible, he says, without Connie, his wife of forty years and his unflagging advocate in the face of constant challenges.

They met at Southern Illinois University in 1968 when she answered his posted notice seeking someone to read his text assignments and type papers for him. It was much later—after their two daughters were grown, after his first bout with cancer, after his career, after his competitive achievements as a golfer—that David Meador decided to try his hand at writing a book. “I had carried the idea with me for a long time,” he says, “but it wasn’t until I got a new computer in 2001 that I had the nerve to tell Connie I was really serious about it.” Not surprisingly, she liked the idea. “It was something concrete for him to take on,” she says, “and it was looking ahead, a new challenge.” His computer, called Voice Note, has Braille and voice-recognition capacities.

They met at Southern Illinois University in 1968 when she answered his posted notice seeking someone to read his text assignments and type papers for him. It was much later—after their two daughters were grown, after his first bout with cancer, after his career, after his competitive achievements as a golfer—that David Meador decided to try his hand at writing a book. “I had carried the idea with me for a long time,” he says, “but it wasn’t until I got a new computer in 2001 that I had the nerve to tell Connie I was really serious about it.” Not surprisingly, she liked the idea. “It was something concrete for him to take on,” she says, “and it was looking ahead, a new challenge.” His computer, called Voice Note, has Braille and voice-recognition capacities.

In the living room of their longtime home, David sat with outstretched arms and explained, as much to himself as to Connie and me, how he came to grips with the task: “In the quietude of this room, I began to lay out the course. It would have eighteen parts, like a round of golf. My first boss, at an insurance company in Chicago, had told me I should take notes in case I ever wanted to write a book. I followed his advice, and those notes were a blessing. Then I started writing, and about a year later, when I had several chapters, I showed them to Connie for the first time.”

She was underwhelmed. “It needed a lot of work. The stories were there, but the structure was not. I wondered—maybe he should give it up, it just wasn’t a practical idea—but he was so determined. We argued a lot. We’re both pretty stubborn.” David could feel Connie smiling, and he smiled, too, and said, “It’s probably the hardest thing we ever did.”

In the mid-2000s they hired a freelance editor, Mary Helen Clarke. “She was more than an editor—she was our arbiter,” Connie said. “She and I kept asking David for changes, but he never got discouraged. Every time he got a chapter back with more suggestions, he rewrote it from start to finish.” Connie grew weary of the process, but David was positively engaged, and that kept them both going. “I was such a believer,” he said. “I wanted to keep turning the page, trying to get it right. I never got tired of working on it.” Finally, in 2009, they declared the eight-year project finished, and everyone directly affected by it—the Meadors, their daughter Julia and her husband, their daughter Emily, two grandchildren, their editor Mary Helen Clarke—welcomed the milestone with relief and joy.

In the mid-2000s they hired a freelance editor, Mary Helen Clarke. “She was more than an editor—she was our arbiter,” Connie said. “She and I kept asking David for changes, but he never got discouraged. Every time he got a chapter back with more suggestions, he rewrote it from start to finish.” Connie grew weary of the process, but David was positively engaged, and that kept them both going. “I was such a believer,” he said. “I wanted to keep turning the page, trying to get it right. I never got tired of working on it.” Finally, in 2009, they declared the eight-year project finished, and everyone directly affected by it—the Meadors, their daughter Julia and her husband, their daughter Emily, two grandchildren, their editor Mary Helen Clarke—welcomed the milestone with relief and joy.

The next hurdle was publication. How? Where? This time, Connie’s instincts prevailed. “We talked to a couple of established presses,” she recalled, “and I think we explored all the options, but in the end we decided to self-publish. After all that time and work, we were eager to have books in hand quickly, and we wanted to retain control of the process from start to finish—the content, the design, everything.” They turned to Lightning Source, the print-on-demand division of Ingram Book Company in Lavergne. On December 10, 2010, Broken Eyes, Unbroken Spirit was formally published. It may not be great literature, but it is a compelling and inspiring story of one unsung couple’s triumph over adversity. We should all aspire to such strength of character as this unassuming account reveals in the lives of David and Connie Meador.

In another generation or so, there may be no more book publishing houses as we know them today. New books printed on paper for mass audiences may be a thing of the past. Practically everything written for post-modern readers may be accessible only by means of electronic devices. But as long as there are printing presses and copy machines, there will be books—written with determination and varying degrees of skill by remnant millions of human beings whose thirst to have their stories known cannot by slaked by images on a backlit screen.

David Meador will read from and discuss Broken Eyes, Unbroken Spirit at BookMan/BookWoman in Nashville on March 22 at 5 p.m.

Copyright (c) 2011 by John Egerton. All rights reserved.