Serious Funnies

Comic artist Gene Luen Yang talks with Chapter 16 about getting graphic in school

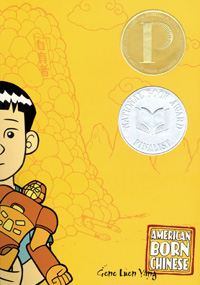

Comic books were once considered strictly kids’ stuff, but by the 1980s graphic novels had begun to compete with traditional novels for top book prizes. Now artist and author Gene Luen Yang wants to see graphic novels taught alongside textbooks and traditional novels in classrooms. Yang’s own autobiographical book, American Born Chinese, was the first graphic novel nominated for a National Book Award and the first to win the American Library Association’s Michael L. Printz Award for excellence in young-adult literature. Prior to his Knoxville appearances, Yang answered questions by email.

Chapter 16: You’ve said that your love of comics began with Superman. What was it about Superman specifically that sold you on graphic storytelling?

Gene Yang: My very first comic book was a Superman comic, but it wasn’t the comic I really wanted. I really wanted a Marvel Two-In-One starring The Thing and ROM the Spaceknight. But my mom thought The Thing and ROM looked too scary, so she bought me Superman instead.

In the Superman story, the atomic bomb drops in 1986. It’s 1984 when I’m reading it—I’m in the fifth grade. The atomic bomb drops and kills off most of the world’s population. The few remnants of humanity that are left gather themselves into these feudal societies. Everything’s pretty lawless, so a group of men get together, dress up in medieval-style armor, and ride around the countryside on these giant mutated dogs to fight crime. Superman survives the bomb (because he’s Superman) and teams up with these Atomic Knights. That comic book warped me. This combination of words and pictures did something inside my brain that neither words nor pictures had been able to do alone.

In the Superman story, the atomic bomb drops in 1986. It’s 1984 when I’m reading it—I’m in the fifth grade. The atomic bomb drops and kills off most of the world’s population. The few remnants of humanity that are left gather themselves into these feudal societies. Everything’s pretty lawless, so a group of men get together, dress up in medieval-style armor, and ride around the countryside on these giant mutated dogs to fight crime. Superman survives the bomb (because he’s Superman) and teams up with these Atomic Knights. That comic book warped me. This combination of words and pictures did something inside my brain that neither words nor pictures had been able to do alone.

I became obsessed with American superhero comics after that. I just loved them. Jeff Yang (columnist for The Wall Street Journal, no relation) has this theory that superheroes have a special appeal for Asian Americans. Most superheroes negotiate two identities. Take Superman, for example. He’s got two names—an American one (Clark Kent) and a foreign one with a hyphen in it (Kal-El). He has two different cultures—American and Kryptonian. He lives two different lives under two different sets of expectations. There’s a lot there for an Asian American kid to relate to. Heck, Superman’s got black hair, wears glasses, and his parents are foreign scientists. I wasn’t conscious of all this when I was young, of course. But the appeal Jeff Yang describes was definitely there.

Chapter 16: Your first graphic novel, Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks, tells the story of a tiny alien IT expert who ends up switching personality elements of the two title characters. A hilarious scenario plays out between a teenage bully and high-school nerd, but it’s also a story about empathy and understanding. What inspired this idea?

Yang: Gordon meets the alien when the alien’s spaceship gets stuck in his nose. That was inspired by my lifelong struggle with sinus problems. For some reason, one of my nostrils is almost always plugged up. (Right now it’s the left one, in case you’re wondering.) It’s frustrating. One day, I got to thinking, “What if something sentient was causing this problem for me?” Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks was born.

There are three major characters in the story: the nerd, the repentant bully, and the unrepentant bully. In various childhood situations and friendships, I’ve played all three roles. When I was a bully, I’d often forget what it was like when I was the victim of bullying. If I’d remembered, I probably would’ve stopped. It’s important to try to walk in other people’s shoes—or at least remember what it was like to go through similar experiences. Cliché, I know, but cliches are sometimes true.

There are three major characters in the story: the nerd, the repentant bully, and the unrepentant bully. In various childhood situations and friendships, I’ve played all three roles. When I was a bully, I’d often forget what it was like when I was the victim of bullying. If I’d remembered, I probably would’ve stopped. It’s important to try to walk in other people’s shoes—or at least remember what it was like to go through similar experiences. Cliché, I know, but cliches are sometimes true.

Chapter 16: Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks was originally self-published. How has the publishing climate changed for graphic novels in the sixteen years since you started out?

Yang: It’s an entirely different world these days. First, the Internet has grown in prominence within the comics world. If I were starting today, I’d probably start with web comics rather than self-published print comics. (I would eventually do print comics, though. I love print.) Second, there’s a market now for the kind of comics I’m making. Sixteen years ago, the middle reader/YA graphic-novel market just wasn’t there. People didn’t have that category in their heads. Heck, back then, folks were predicting the death of the American comic book. Marvel had declared bankruptcy. Manga was still a niche hobby. Most people hadn’t heard of the term “graphic novel.” The changes between then and now are just amazing.

Chapter 16: You are probably best known for your graphic novel American Born Chinese, a book that explores complex questions about race, identity, and cultural heritage. It weaves the Chinese legend of the Monkey King together with a contemporary story of two boys: one born to Chinese immigrants living in an American suburb and one an American embarrassed by visits from his Chinese cousin. For you, what was the advantage of telling this story from multiple points of view?

Yang: I wanted the three story lines in American Born Chinese to read very differently from one another. The Monkey King story would read like a storybook with a third-person voice. The Jin Wang story would be like a personal-journal comic with first-person captions. The Cousin Chin-Kee storyline would be like a sitcom, complete with a laugh track. I hoped that attacking the issue from three different vantage points would give the book a certain richness and make the final coming-together of the three more compelling.

Yang: I wanted the three story lines in American Born Chinese to read very differently from one another. The Monkey King story would read like a storybook with a third-person voice. The Jin Wang story would be like a personal-journal comic with first-person captions. The Cousin Chin-Kee storyline would be like a sitcom, complete with a laugh track. I hoped that attacking the issue from three different vantage points would give the book a certain richness and make the final coming-together of the three more compelling.

Cultural identity is a complex issue. I still go back and forth in all sorts of ways when I mull it over in my head. Maybe breaking up American Born Chinese into three distinct pieces made it more manageable for my brain.

Chapter 16: You’ve advocated for the use of graphic novels as learning tools in schools. Your next book, Boxers and Saints, will tell the story of China’s Boxer Rebellion. Is this the kind of project that would be right at home in a high-school history class?

Yang: Boxers and Saints is fiction, but I did a lot of historical research. I didn’t know much about the Boxer Rebellion when I started. After all, it gets about a paragraph in your average American history textbook. As I learned more, though, I realized how many parallels the Boxer Rebellion has to today’s world.

The Boxer Rebellion occurred in the year 1900. Back then, the Chinese government was incredibly weak and couldn’t defend China’s borders. It allowed the Western powers to go in and establish concessions—small communities of Westerners that basically functioned like colonies—in all the major cities. The poor, illiterate teenagers of the Chinese countryside were embarrassed by this, so they came up with this elaborate ritual where they would call Chinese gods from the heavens to possess them and give them superpowers. Then, armed with these powers, they marched across the land killing foreign missionaries, foreign merchants, foreign soldiers, and Chinese Christians—their fellow countrymen who had embraced foreign religion. Because their martial arts reminded the Europeans of boxing, these teenagers became known as the Boxers.

The Boxers of old China have a lot in common with the terrorists of today’s Middle East. Both are groups of mostly poor young men with little hope for the future. Both feel humiliated by the foreign presence in their homelands. Both look to strange (to our minds, anyway) spiritual beliefs for power.

In Chinese culture, there’s a tradition of talking about present-day situations by talking about historical or fictional parallels. Discussing current situations can sometimes get too emotional. We’re too close to see clearly. Maybe the Boxer Rebellion (and Boxers and Saints) can serve this purpose in present-day American classrooms.

[This interview originally appeared on February 27, 2013.]

Joe Nolan is a writer and intermedia artist in Nashville. His articles about homelessness and poverty have been published by The Contributor, translated into three languages, and reprinted across Europe.