Shake It Off

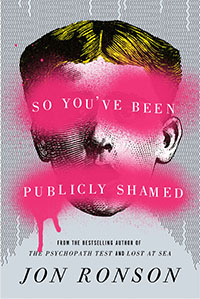

In So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, Jon Ronson peers into the Internet abyss and challenges haters not to hate

“Over the years, I’ve sat across tables from a lot of people whose lives had been destroyed,” the British journalist Jon Ronson writes in his excruciating, un-put-downable new book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. “Usually the people who did the destroying were the government or the military or big business. … Justine Sacco felt like the first person I had ever interviewed who had been destroyed by us.”

The destruction came soon after Sacco posted this unfortunate tweet, just before boarding a plane: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m White!” For the eleven hours she was in the air—thanks in part to a post on the tech site Valleywag, which extended the tweet’s reach way beyond Sacco’s 170 Twitter followers— the Internet whipped itself into an outraged frenzy that eventually became the hashtag #HasJustineLandedYet. It was a gleeful pile-on that predicted and reveled in the nightmarish cell-phone switch-on that awaited her on arrival in South Africa. Sacco was called horrible names thousands of times over by people who didn’t understand that the joke (albeit not a great one) was meant to parody racism, not proliferate it. Sacco trended worldwide on Twitter in the worst way. She was also fired from a job she loved.

If you spend a lot of time on the Internet, reading So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed can feel a bit like a haunting from the ghosts of your browsing history. The names may sound familiar, but you won’t remember why until the first details of the story spill out: Lindsey Stone (posted a jokingly “disrespectful” photo of herself in Arlington Cemetery), Adria Richards (tweet-shamed a guy for a “dongle” joke; he was fired, and she was hit with horrific threats), and so on. If you’re not a social-media obsessive, madly refreshing your feed all day, some of the digital mob actions detailed here may seem as bizarre as they are cruel. Either way, Shamed is an engaging, energetic read that manages to be funny and surprising while attempting to place an emerging phenomenon in historical context.

If you spend a lot of time on the Internet, reading So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed can feel a bit like a haunting from the ghosts of your browsing history. The names may sound familiar, but you won’t remember why until the first details of the story spill out: Lindsey Stone (posted a jokingly “disrespectful” photo of herself in Arlington Cemetery), Adria Richards (tweet-shamed a guy for a “dongle” joke; he was fired, and she was hit with horrific threats), and so on. If you’re not a social-media obsessive, madly refreshing your feed all day, some of the digital mob actions detailed here may seem as bizarre as they are cruel. Either way, Shamed is an engaging, energetic read that manages to be funny and surprising while attempting to place an emerging phenomenon in historical context.

As Ronson walks through various online missteps and the resulting disproportionate reaction, each example serves as a queasy reminder of how easy it is to witness a stranger’s humiliation metastasize into full-blown virality in real time. The book also reminds us that our infinitely scrolling media streams quickly wash such people out of sight even as Google pins their gaffes to the top of the search-result page—the Internet’s merciless equivalent of the public scaffold. Thus are largely forgotten people forever defined by their transgressions, however trivial. (Reclaiming one’s search results, a meticulous and expensive process, gets some attention in later chapters—one of many fascinating rabbit holes Ronson leads readers down in service of the larger story.)

Part of Ronson’s pitch is that he, too, was once a happy shamer. In the book’s opening pages, he recounts a confrontation with some programmers who had created a fake Jon Ronson Twitter account. He posted a video of the exchange on YouTube, delighting in the support that rallied behind him, which ultimately shamed the tech guys into taking down the account. “I was happy to be victorious,” Ronson writes. “It felt wonderful. The wonderful feeling felt like a sedative.”

By the end of his book-long dive, the sedative has worn off, and a harsh reality taken its place. “The powerful, crazy, cruel people I usually write about tend to be in far-off places,” he writes after meeting with Ted Poe, the showy, public-shaming judge-turned-Republican-congressman. “The powerful, crazy, cruel people were now us. It felt like we were soldiers making war on other people’s flaws.” No zealot like the convert, perhaps, as Ronson sets about to convince us that this public-shaming stuff is bad for everyone involved. It also doesn’t work, at least when aimed at white men involved in sex scandals.

It helps his case immensely that Ronson is a vivid and very funny storyteller, as you already know if you’ve read any of his other books (The Psychopath Test, The Men Who Stare at Goats) or heard him on the radio. And he’s at his best in relaying scenes where people tell their own stories, in all their pathos and pain. Sacco, hitherto known to most only as some publicist who posted a bad tweet and should have known better, appears before us as a real, living, feeling human being. Ronson’s compassion and eye for mannerisms are a gift, and the way he relates the story of Michael Moynihan as he agonizes over whether to hit send on a story he knows will ruin another journalist’s reputation is masterfully paced. Not to mention anxiety-inducing and nearly unbearable.

The journalist in question is—spoiler alert—disgraced former New Yorker staff writer Jonah Lehrer. To recap quickly: Lehrer fabricated some Bob Dylan quotes in his book Imagine. He also plagiarized another writer, Christine Jarrett, on his blog. He recycled his own words in various ways at various times. And he lied to Michael Moynihan about these and other serious journalistic lapses. Eventually Lehrer was invited to give a public apology at a Knight Foundation event, during which a giant screen showed a live Twitter feed of people not accepting his apology, partly because he didn’t so much apologize as try to rationalize his plagiarism. (At one point, he compares himself to an FBI agent.)

The journalist in question is—spoiler alert—disgraced former New Yorker staff writer Jonah Lehrer. To recap quickly: Lehrer fabricated some Bob Dylan quotes in his book Imagine. He also plagiarized another writer, Christine Jarrett, on his blog. He recycled his own words in various ways at various times. And he lied to Michael Moynihan about these and other serious journalistic lapses. Eventually Lehrer was invited to give a public apology at a Knight Foundation event, during which a giant screen showed a live Twitter feed of people not accepting his apology, partly because he didn’t so much apologize as try to rationalize his plagiarism. (At one point, he compares himself to an FBI agent.)

In addition to the impossible project of making Lehrer seem like a sympathetic character, to which he dedicates a significant amount of space, Ronson commits himself to delving into the history of public-shaming at its barbaric peak and warning us of the consequences of its return. The book is less successful in these two realms.

While it’s instructive to connect the current atmosphere of online shaming to eighteenth-century public-shaming rituals, the comparison doesn’t hold quite as much water as Ronson wants to pour into it. He cites the case of Abigail Gilpin, who in 1742 was sentenced, along with the man she’d been found “naked in bed” with, to be “whipped at the public whipping post twenty stripes.” In the case of someone like Jonah Lehrer, Ronson discovers, the period punishment for “lying or publishing false news” was to be “fined, placed in the stocks for a period not exceeding four hours, or publicly whipped with not more than forty stripes.”

Public punishments “didn’t fizzle out because they were ineffective,” Ronson writes. “They were stopped because they were far too brutal.” That sounds about right. But he also directly compares the public-whipping sort of punishment with what Lehrer endured—namely, watching people tweet mean things about him while delivering a speech for which he was paid $20,000. Enduring deluge after deluge of insults, threats, and other nastiness via the Internet is certainly real and harmful, but it isn’t the same thing as being marched out in front of a crowd and physically assaulted by an agent of the government.

All that said, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed is an utterly gripping read, packed with humor and compassion and Ronson’s characteristic linguistic juggling of the poignant and the absurd. And while he may raise more questions than he can fully answer, Ronson manages to grapple with human shame, survey contemporary social media, question the popularly held view of the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, estimate the profit Google likely made off search results for Justine Sacco’s name during the worst days of her life, and bear witnesses to an extreme-porn shoot—all while asking us to listen to the better angels of our nature. That would be an accomplishment in a book one-tenth as entertaining as this one.

Steve Haruch lives in Nashville. His writing has appeared at NPR’s Code Switch, The New York Times, and the Nashville Scene, where is he is a contributing editor.