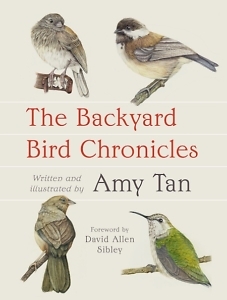

She’s on the Bird

Amy Tan turns her discerning eye to the avian world

Amy Tan, a devoted backyard birdwatcher, frequently has questions for her avian visitors, some answerable, some not. For example: Are they fleeing fires north of where she lives in Sausalito, California, and taking refuge in her backyard? Do birds frown? Do certain goldfinch movements signal an impending attack of another finch? Why are certain birds feeding in certain locations, in certain ways — is it a dominance ritual, or just their mood? Is this hummingbird’s fancy footwork some kind of courtship move? Are those crows mourning? Why does the sparrow return to the window ledge?

The questions never stop coming, no matter how long Tan surveys the bird scene, no matter how knowledgeable about it she becomes, and no matter how many thousands of mealworms she offers. Pondering what she doesn’t know, or can’t see, is one of Tan’s consistent pleasures as a birdwatcher; and her inquisitive nature imbues her new illustrated book The Backyard Bird Chronicles with a delightful sense of inquiry and mystery. Tan is best known as a great American novelist; she is the author of the canonical The Joy Luck Club, among other books, and a member of the American Academy of Letters. Now, she’s on the bird — I mean board — of the American Bird Conservancy and has added the art of illustration to her skills. Since cracking open her first sketchbook at age 64, Tan has studied with the naturalist John Muir Laws and clocked many hours of daily sketching, what Laws calls “pencil miles.”

In nature-journal fashion, Tan’s dated entries range from 2018 to 2022, with accompanying pages from her sketchbook for each. These are punctuated by her gorgeous portraits of birds, from dark-eyed juncos to a juvenile Cooper’s hawk to lesser goldfinches. As it turns out, writing novels and watching birds requires, and inspires, a similar contemplative, imaginative noodling. “With both fiction and birds,” she writes in the book’s introduction, “I think about existence, the span of life, from conception to birth to survival to death to remembrance by others. I reflect on mortality, the strangeness of it, the inevitability.”

Spanning four years of close watch, the book is essentially plotless, which feels refreshingly radical in a publishing era of narrative-propulsion worship. Which is not to say that Chronicles is without tension, and, as any nature-lover will expect, sorrow. A salmonellosis outbreak strikes a pine siskin, forcing Tan to take all her feeders down, and a fox sparrow is hobbled by deformed feet. Wildfires rage to the north, sending refugees to Tan’s “spa,” an expanse of oaks, a house with a green roof, multiple suet and seed feeders and birdbaths, and a camellia bush situated just outside Tan’s bathroom window, where she follows their antics while brushing her teeth. (But even the spa sees days of terrible air quality.) Observing a goldfinch with swollen eyes, she writes, “Such heartbreak comes with love and imagination.”

And yes, the pandemic comes along, ushering in legions of newly besotted birdwatchers. But in March 2020, Tan is already a fixture at the window; circumstances, though deeply grim, align in her birdwatching favor.

Her descriptions of the lucky birds who frequent the “spa” have a deft, light touch, and she is frequently funny. “I am controlled by birds,” she writes, calculating her mealworm tab. She revels in imagining the birds’ motivations and does a fine job of subtly revealing what she’s learned about their behavior over the years, while occasionally poking fun at herself and other bird-brains, particularly the admonishing “pooh-bahs” of Facebook birdwatching groups. Describing a squabble between a California towhee and a scrub jay, she reflects, “I am aware I have committed the naturalist’s sin of stereotyping the towhee as jolly and the Scrub Jay as conniving. Science would require me to be objective and to not let personal bias obstruct more accurate observations. Thank God I am not a scientist. I love the jolly towhee and the smart and conniving Scrub Jay.”

Her descriptions of the lucky birds who frequent the “spa” have a deft, light touch, and she is frequently funny. “I am controlled by birds,” she writes, calculating her mealworm tab. She revels in imagining the birds’ motivations and does a fine job of subtly revealing what she’s learned about their behavior over the years, while occasionally poking fun at herself and other bird-brains, particularly the admonishing “pooh-bahs” of Facebook birdwatching groups. Describing a squabble between a California towhee and a scrub jay, she reflects, “I am aware I have committed the naturalist’s sin of stereotyping the towhee as jolly and the Scrub Jay as conniving. Science would require me to be objective and to not let personal bias obstruct more accurate observations. Thank God I am not a scientist. I love the jolly towhee and the smart and conniving Scrub Jay.”

Tan’s commitment — both to the care and feeding of birds and to her journaling and portraiture — is impressive, and her affection for all of it, infectious. In fact, while I was reading this book, a pair of bluebirds began building a nest in one of my family’s backyard bird boxes — a first in the 15 years we’ve lived here, after many springs of watching them check out the box, only to dip out for parts unknown. I hope to give our new bird friends some fraction of the reverent attention that Tan, to her readers’ benefit, allows hers.

Susannah Felts is a writer based in Nashville. Her writing has appeared in The Best American Science and Nature Writing, Joyland, Oxford American, Guernica, Literary Hub, and elsewhere.