Siblings in Exile

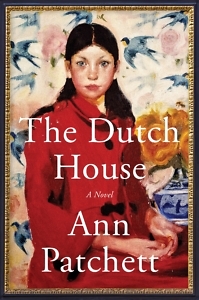

A brother and sister wrestle with the past in Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House

From school shootings to toddlers in cages, our historical moment can feel like a Grimm’s fairy tale. It’s no surprise, then, that our leading novelists have often couched their work in a fable-like realism: Think of two recent Pulitzer Prize winners, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch and Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, which sprinkle pixie dust over the horrors of terrorism and World War II. Ann Patchett’s mesmerizing, gorgeous new novel, The Dutch House, falls squarely in this tradition. Spanning from the 1950s to the present, it traces the complex and often torturous history of a modern Hansel and Gretel and the alluring mansion they called home, once upon a time.

Seven years younger than his sister Maeve, Danny Conroy, the narrator, can’t recall his mother, who abandoned her husband, a Philadelphia real estate mogul, and their two children under mysterious circumstances. There’s a whiff of secrets and sorrow in their home, the beautiful Dutch House, with its dormers and gilt dining room, its enigmatic paintings and rolling lawns (all meticulously described here) — and yet Danny and Maeve thrive, preternaturally close, nurtured by a loyal housekeeper and cook and the occasional bone of affection tossed out by their aloof father, Cyril.

Their idyll is disrupted when their father marries a younger social climber with two small daughters of her own. Andrea’s a wicked stepmother straight from central casting, scheming to cheat Maeve and Danny of any claim to their father’s fortune. When Danny is 15, Cyril Conroy dies of a sudden heart attack, and Andrea sees her opportunity to banish the Conroy children from the Dutch House, forcing them to write a new script for their lives. Maeve, a Barnard-educated math prodigy, takes a job with a frozen-food company, while Danny dutifully pursues chemistry and medicine at Columbia.

Much of the novel pivots around the Conroys’ exile and their furtive visits back to the Dutch House. Over the decades Maeve and Danny park across the street, smoking cigarettes and cursing Andrea while trying to piece together the riddles of their youth. Their former home draws them like a magnet. As Danny observes, “I was still at a point in my life when the house was the hero of every story, our lost and beloved country. There was a neat little boxwood hedge that had been trained to grow up and over the mailbox, and I wanted to get out of the car and go across the street and run my hand over it.”

But the nostalgia thins as the years pass. Danny weds and becomes a father and quits medicine. His wife clashes with Maeve, who remains single and lives in a modest bungalow. Careers rise and fall; marriages falter; and the visits to the Dutch House trail off. “There was no extra time in those days and I didn’t want to spend the little of it I had sitting in front of the goddamn house,” Danny says, “but that’s where we wound up: like swallows, like salmon, we were the helpless captives of our migratory patterns.”

But the nostalgia thins as the years pass. Danny weds and becomes a father and quits medicine. His wife clashes with Maeve, who remains single and lives in a modest bungalow. Careers rise and fall; marriages falter; and the visits to the Dutch House trail off. “There was no extra time in those days and I didn’t want to spend the little of it I had sitting in front of the goddamn house,” Danny says, “but that’s where we wound up: like swallows, like salmon, we were the helpless captives of our migratory patterns.”

Those migrations comprise a kind of spiritual journey, as well. The Conroys are staunch Catholics, given to pieties and rituals that take a toll. Their faith is braided into the fabric of daily routines. Danny’s trek into middle age morphs into a pilgrim’s progress as he climbs difficult hills and skirts sloughs of despond. Patchett is mindful of the allegory beneath the carefully wrought surface of Danny’s life.

The Dutch House is a big-hearted, capacious novel, like the dwelling at the center of it, with Dickensian touches throughout. Its characterization varies with mileage, but the novel’s exploration of family and place is as searching as any in Patchett’s oeuvre, as she limns the pain of even the most privileged. There’s an affecting twist in her final act, leading to yet more tragedy — as Danny notes of a minor figure, “His grief was a river as deep and wide as my own.” Danny’s celestial city proves elusive, but as Patchett suggests, the striving may be the point, even if it leaves a bittersweet taste to “happily ever after.”

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for O, the Oprah Magazine; the Minneapolis Star Tribune; and The Barnes & Noble Review. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.