Soaking Up the Voices

Lee Martin talks with Chapter 16 about telling the stories of people on the margins

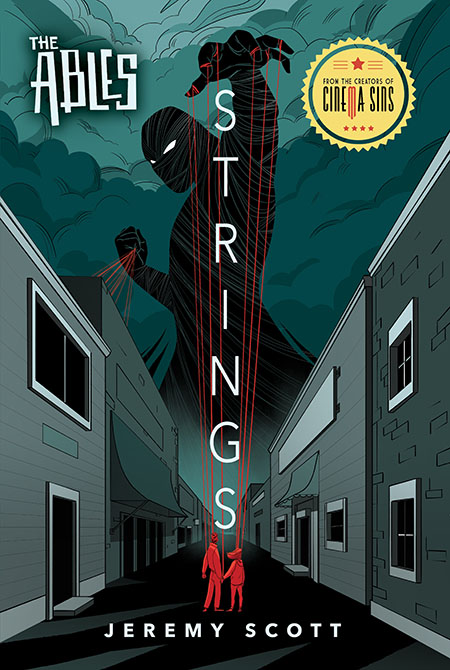

Lee Martin’s novel The Bright Forever was a finalist for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize. Set in a small Indiana town, the story revolves around the disappearance of a nine-year-old girl. Quakertown, Martin’s first novel, concerns a young black woman in racially segregated North Texas who is in love with two men: one white, one black. In River of Heaven, the follow-up to The Bright Forever, Martin’s narrator is an elderly gay man holding on to a horrifying secret. And in Martin’s new novel, Break the Skin, two female narrators, separated by hundreds of miles, unwittingly share the love of the same man, a connection that binds them to a shocking crime.

A Lee Martin novel combines the fast pacing and suspense of a thriller with the craftsmanship and lyricism of literary fiction. Reviewing his newly released novel, Break the Skin, for The New York Times, Adam Langer grouped Martin with Dan Chaon, Tom Franklin, and Ron Rash, authors “who write harrowing and intellectually challenging crime novels set in small-town America.” One of Martin’s chief tactics is the drawn-out reveal; his characters cling to their secrets as long as they can, unburdening themselves slowly, layer by layer. In Martin’s fiction, revelation can lead to punishment (prison, retribution, outcasting), but it also, almost always, leads to freedom. We are only as sick, his fiction argues, as our secrets.

Break the Skin is narrated by two women. Laney Volk is a nineteen-year-old Walmart worker in Mt. Gilead, Illinois. “I was the sort most folks didn’t give a second look,” she says, “a scrawny thing with short curly hair, a nothing kind of girl with no hips to speak of and arms and legs as thin as ropes. I looked like I might turn to dust…” Her counterpart, Betty Ruiz, living 700 miles south in Denton, Texas, goes by the name of Miss Baby. She is the thirty-something owner of Babyheart’s Tats: “You want barbed wire on your bicep? A rose on your ankle? A heart with an arrow through it on your forearm? I’m your gal. …. But don’t come asking for the nasty. No tats on your ta-tas. No rat-a-tat-tat anywhere near your bird or your back door. Go on down the street if that’s your kick. Miss Baby runs a classy place.”

Break the Skin is narrated by two women. Laney Volk is a nineteen-year-old Walmart worker in Mt. Gilead, Illinois. “I was the sort most folks didn’t give a second look,” she says, “a scrawny thing with short curly hair, a nothing kind of girl with no hips to speak of and arms and legs as thin as ropes. I looked like I might turn to dust…” Her counterpart, Betty Ruiz, living 700 miles south in Denton, Texas, goes by the name of Miss Baby. She is the thirty-something owner of Babyheart’s Tats: “You want barbed wire on your bicep? A rose on your ankle? A heart with an arrow through it on your forearm? I’m your gal. …. But don’t come asking for the nasty. No tats on your ta-tas. No rat-a-tat-tat anywhere near your bird or your back door. Go on down the street if that’s your kick. Miss Baby runs a classy place.”

The women are connected through their love for Lester Stipp, an Iraq War veteran whose post-traumatic stress includes bouts of dissociative fugues, states in which he forgets, for periods that may or may not last for weeks, his identity. Much of the book’s tension results from not knowing how much to trust Lester, whose diagnosis stems from his involvement in an almost unspeakable war crime.

While Martin is a Pulitzer finalist as a novelist, he also writes short stories (The Least You Need to Know) and has penned two highly regarded memoirs, From Our House and Turning Bones. A professor of creative writing at Ohio State, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: Your protagonists have a way of grabbing the reader by the throat. I’m thinking of Henry Dees in The Bright Forever, who directly asks the reader several times to keep reading, and Sam in River of Heaven, who says, “This may not seem like much, this story I’m telling, but you have to understand what it is to be me….” In Break the Skin, both Laney and Miss Baby believe that telling their story will set them free. Why is storytelling so important, and not just for your characters, but obviously for you, a memoirist, as well?

Lee Martin: It seems to me that telling stories is one of the ways we try to make sense of the world and our place in it. People tell stories. Not just certain kinds of people, but all people. It’s part of being human. It’s a way of documenting our existence. Even if someone isn’t putting the story into written form the way writers do, or recording it as oral history, narrative is still narrative. The spoken narrative, even in its most banal form, is a way of saying, “This matters,” and, more than that, “I matter,” and “We matter.” Story is the language of the human tribe.

My own fascination with narrative came from listening to my father—and other men in our rural part of southeastern Illinois—tell stories. Those stories were like currency among these farmers and factory workers and oil-field roughnecks. Whoever told the best story held sway for however long it took for him to tell the tale. Men built reputations as great storytellers, and I became fascinated at an early age with the power of the what then, what then, what then. A good story raises questions about what it is to be human. A good story entertains while also carrying us deep into what Faulkner called “the old verities and truths of the heart.” A good story shows us to ourselves, and lordy don’t we need that?

When I write a novel, I live inside a character like Henry Dees in The Bright Forever, or Sam Brady in River of Heaven, or Laney and Miss Baby in my new novel, Break the Skin. The longer I live with those characters, even if they’re very much unlike me, the more I begin to see that they and their circumstances matter for what they can demonstrate about the complexity of all of us. They bring up essential questions about family, and loyalty, and goodness, and deceit, and selfishness, and love. The things that make up our day-to-day to and fro. They’re the same questions that I explore in a memoir like From Our House. What does it mean to claim that we love someone, and how does that claim sometimes bump up against our worst flaws? Finally, what does it take to stay on the side of goodness, faithfulness, selflessness? What does it take to be the best person we can be, knowing that sometimes we’ll fail? Storytelling helps me feel more alive, more connected to myself and those around me. To me, the wonderful thing is, there’s always the need for more stories because human experience is just too complicated and mysterious to ever be fully explained.

Chapter 16: So if the storytelling is important to finding out who we are—“a good story shows us to ourselves”—then what about narrators like Henry Dees, who lies to almost everyone he deals with (including the reader, including himself), or Sam Brady’s brother Cal, who, when he first tells the story to Sam of his involvement in the bombing plot, may or may not be telling the truth? And of course Laney and Miss Baby can’t be entirely trusted, either. What are the unreliable storytellers showing us? And do they teach us anything about our own truthful stories?

Lee Martin: They’re showing us that people often lie to themselves even when they think they’re telling the truth. There’s always something mysterious and contradictory submerged in people. In fiction, a character’s action—and the narrative it creates—applies pressure to that character until some additional aspect of his or her nature can’t stay hidden. In my own work, I’m interested in characters who have stories that they’d rather not tell. Again, the pressure of action and consequence within the frame of the narrative makes it impossible for these characters to stay silent. Finally, as in the case of Henry Dees, Sam Brady, Laney Volk, and Miss Baby, characters tell the stories they’ve fought so hard throughout the individual novels to keep from telling.

All narrators are unreliable in the sense that as soon as they begin to speak, they put a particular spin on the story. They tell the tale they want to tell, the one they want to believe in. There’s always a contradictory story beneath the surface. That’s the interesting story, the one that gives us more truth about the character than we ever imagined we’d get. When I write memoir, I have to treat myself the same way I treat a character in a novel. I have to dramatize the episodes of my life that revealed something about me that I either didn’t know or tried my best to cover over. Memoir is a genre of honesty—or should be—and I have to shape experience in a way that forces me to tell the story I’d rather not tell.

Chapter 16: In your novels, that pressure to make your characters tell the story beneath the surface often comes from the law, yes? The law is ever-present in each of your last three novels, but there seems to be little ambivalence about The Law itself, with a capital T and capital L. In Break the Skin, for example, none of the characters, including Laney and Miss Baby, ever question what is right or wrong, or what right and wrong mean. When they transgress (and almost all the Break the Skin characters transgress in some form), they seek understanding, but they never question the need to pay for their transgressions. So while their actions can seem almost honorable (if doing everything you can for love is honorable), they don’t ask (the universe? god? mama?) why what feels so right can be so wrong.

Lee Martin: The law, or some character who represents what I like to call “the right-thinking world,” is always present in my novels: the county sheriff in The Bright Forever, the newspaper reporter in River of Heaven, the police in Break the Skin. Their presence contributes to my main characters’ choices to finally tell the truth. A larger contributor, though, particularly in The Bright Forever and River of Heaven, is those characters’ sense of guilt. Henry Dees and Sam Brady have both lived a number of years with their guilt. They’ve lived to the point where they have to tell the truth for the sake of confession in the hope that they’ll find some sort of redemption.

Things are perhaps a tad different in Break the Skin, where characters like Delilah, Rose, Tweet, Laney, and Miss Baby are caught up in the pleasures of the moment. Whatever will satisfy those pleasures seems right to them, and so they act. Furthermore, they feel that they deserve those pleasures. And to some degree they’re right. Like all of us, they deserve human connection and a feeling that they matter to someone else. They live, you see, on the other side of right thinking, which I imagine we all do from time to time. As Miss Baby says early on, “Sometimes you don’t have a choice.”

That’s what I’ve learned. Sometimes things happen, and there you are. So there they are, in a mess of trouble born from loneliness, desperation, and a disregard for consequence. When people have so little, a chance in the present counts so much more than a consequence on down the road. Still, Laney particularly has a moral conscience, if only in retrospect. She admits she should have gotten out of the revenge plot against Rose. She says she should have gone to the police. At the end of the book, she owns up to everything she did or failed to do that was wrong. She says it will all haunt her forever. She daydreams about what life might have been like for her if she hadn’t loved Delilah so much. So, at least with Laney, there’s a recognition of her own missteps and what they’ve cost her.

Chapter 16: You write from various perspectives and points of view. In The Bright Forever, you write not only from first-person perspectives but also from the third-person and even, if I remember right, from the perspective of the community itself, in a kind of Greek Chorus maneuver. In River of Heaven, the entire story is told by the one narrator, Sam Brady. And in Break the Skin, you’ve got the two narrators, Laney and Miss Baby. Are there formal reasons for these choices, or do you go with what feels right?

Chapter 16: You write from various perspectives and points of view. In The Bright Forever, you write not only from first-person perspectives but also from the third-person and even, if I remember right, from the perspective of the community itself, in a kind of Greek Chorus maneuver. In River of Heaven, the entire story is told by the one narrator, Sam Brady. And in Break the Skin, you’ve got the two narrators, Laney and Miss Baby. Are there formal reasons for these choices, or do you go with what feels right?

Lee Martin: The point of view should be the one that best allows the novel to explore what stands at its center, and thereby allow the reader to have the experience that you want him or her to have with the material. When I began working on The Bright Forever, I wrote nearly 200 pages in a third-person limited point of view that allowed me to concentrate on the crime that stands at the heart of the book. Those 200 pages taught me that I was more interested in how that crime radiated out through the various populations of the small town of Tower Hill. That’s when I knew I wanted to let a group of first-person narrators speak from their perspective as influenced not only by the crime but also by social class, education, economics, religion, history, etc. I also knew that I wanted a collective consciousness of the community to come into play, offering up the perspective of those townspeople who were out searching for the missing girl. I particularly needed that perspective in order to establish the Mackeys as the golden family of the town. River of Heaven is actually Sam Brady’s confession; to my way of thinking, a sustained first-person narrative best allowed that confession.

Now, in Break the Skin, I was interested in matters of human connection and disconnection. I was also interested in how we can be going through our lives, not knowing that something someone does or doesn’t do—I’m talking about people we may not even know—can have an irrevocable effect on who we’ll eventually become and the lives we’ll have from that point on. I wanted, then, to allow that experience for the reader by way of Laney and Miss Baby, our first-person narrators, separated by geography but bound together by the man they at first don’t know they share.

Chapter 16: You dedicate Break the Skin to Miss Baby, who is, of course, one of the narrators and, really, a figment of your imagination, yes? Was her voice that powerful to you?

Lee Martin: Yes, her voice was that powerful to me, and she was actually the character who spoke to me first. She came onto the page with great force, and though her first section is now the second section of the book, following Laney’s opening, in the first draft the book opened with Miss Baby. She started talking to me—“This is the truth. Lordy Magordy. Listen. He was just there”—and I just kept listening while I found the right plot moves that put pressure on her to say more.

Chapter 16: She has fascinating speech patterns, veering from a kind of Texas drawl to Spanish to Spanglish. Is there a model for her, or did that voice just kind of come on organically?

Lee Martin: No, not a model that I can identify. I imagine I’d registered her voice from a number of people I’ve encountered in my life. It was truly a matter of hearing her speak and then following what she had to say. I try to create my characters from the inside out. So, again, if I know their worlds, I’ll know their voices, and the narration will indeed be an organic process.

Chapter 16: Is writing in a nineteen-year-old female voice any harder or easier than writing in other voices? In The New York Times, Adam Langer notes that in Break the Skinyou succeed in creating a more convincing female character’s voice than Jonathan Franzen does in Freedom or Phillip Roth does in The Human Stain. As a writer, are any voices off limits? I mean, you’ve written in the voice of a pedophile, but are there any voices that you wouldn’t, on principle, write in?

Lee Martin: Well, first, I assume when you make reference to writing in the voice of a pedophile, you’re referring to Henry Dees in The Bright Forever, yes? I’ve never thought of Mr. Dees as a pedophile. I think of him as a reclusive man who has a paternal affection for Katie Mackey. His problem is his own family never taught him the proper expression of love, and because of that he’s always questioning his behavior around Katie. He doesn’t sexualize her; in fact, he objects to the fact that her mother lets her put on red fingernail polish one evening. He’s an unmarried man who will have no child of his own, an odd duck in the community, and he doesn’t quite know what to do with this affection that he has for Katie. That’s what eventually costs him and keeps him from doing the right thing.

But that’s neither here nor there as far as the question you’ve asked about writing in Laney’s nineteen-year-old voice. Writing in any distinct voice that’s the product of gender, ethnicity, social class, etc. is a matter of immersing oneself in the world of that particular character and then paying attention. Listening is a skill that we all need as writers, as well as a curiosity about other people, particularly people who are different from us. Soak up that person’s world, and you soak up his or her voice. It’s just there ready to be tapped when you’re ready. When I wrote Break the Skin, I did what I do with the main characters of any novel; I tried to live inside the world and the consciousness of both Laney and Miss Baby. I let them speak from their individual worlds, with which I had a degree of intimacy, and I tapped into the voices that I’d already registered from those places and from the people upon whom I patterned the characters. I strongly believe that the novelist’s art is in part an act of empathy. I’m always trying to understand how my characters and their situations came to be, and to do that I have to live in their worlds. Is there a voice I’d avoid on principle? I really can’t say. I’m fascinated by all sorts of people. I’m always trying to understand the why of them, and sometimes that why comes most clearly from their own words.

Chapter 16: I want to ask about the music in Break the Skin. There’s a Columbus, Ohio, band called Watershed that both Laney (in Illinois) and Miss Baby (in Texas) go to see. And then there’s Lucinda Williams, who is an important musician for Laney.

Lee Martin: The title of Break the Skin actually comes from a Watershed lyric—a song called “Black Concert T-Shirt”—and I’m grateful to Joe Oestreich and Colin Gawel for allowing me to use the lyric as an epigraph. I love their band, and it gave me a kick to give them a couple of cameos in the book. Their music has that power-rock edge that underscores nicely the driving desire that the characters in the novel have for love. A lasting love.

And of course that’s the thing with Lucinda Williams. Her music is all about the ins and outs of love and what it means to our lives. She’s not afraid to ugly things up. She’s not afraid to write about loneliness, desperation, and beneath it all an abiding hope. My characters live inside that world, so her music was a natural fit for Delilah and especially Laney, who says about Lucinda, “I loved her sad-old, wise-to-the-world ways, and that voice that told you she’d been hurt every way there was for a women to be hurt, and still she hoped for love.” That’s the sort of woman Laney is on her way to becoming, the sort of woman like Delilah, but with so much more to lose.

Chapter 16: Break the Skin is filled with spells and hexes and witchcraft, or at least an experimentation with them. What made you want to incorporate that theme into the book?

Lee Martin: The book is based on a true story about a woman in a small Midwestern town who convinced three other people that a young girl had placed a hex on all of them. I wanted to try to figure out how a fairly unremarkable woman could have that sort of sway over others. I wanted to see if I could construct the worlds and the histories of these characters in a way that would convince us that what Alice Hoffman has called practical magic would have an appeal for them. “You have to understand what happens to people who start to believe they have no choice,” Laney says. “People like us. We had so little—or in my case, I’d thrown too much away—and we were fierce to protect what was ours.” These characters live on the margins; they’re the have-nots. How much does it take for someone in that position to believe that a little magic might indeed offer them a degree of control that their regular lives don’t offer them? Why do everyday folks buy lottery tickets? A belief in luck. How far away from magic is luck? I was concerned with the believability factor, but I also wanted to take on the challenge. I didn’t want to back away from it. I wanted to explore it and find out the whys of it. I’ll leave it to the readers to decide how well I did.

Chapter 16: And finally, can you imagine yourself writing a novel set in a big city where no one has any secrets?

Lee Martin: Oh, I might set a novel in a big city. Sure. I have to tell you, though, that I’m very happy letting my novels provide a voice for the folks I see living on the margins on farms and in small towns in the Midwest. Sometimes those people don’t have much of a voice in our country, and when someone doesn’t have a voice, it becomes easy for other people to stereotype and ultimately dismiss them.

I don’t want that to happen because these folks I’m talking about are no different from those who have more influence. At heart, they all want the same thing. They want to matter, and if my novels can play at least a small part in allowing that, then I’m pleased. I watched my father work himself to death on an eighty-acre farm in southeastern Illinois. My mother retired from teaching grade school for thirty-eight years and then went to work in the laundry room of a nursing home. There were plenty of folks who had it much worse than we did, and even if it appeared that our comings and goings didn’t have much significance in the larger world, we were still individuals with our own longings and joys and hopes and disappointments, etc. The particular life, even if it’s one lived in an out-of-the way place, has everything to show us about what it is to be human.

I’ll keep looking to characters who give me further opportunity to think more about what a complicated human tribe we are. Secrets are such a large part of that tribe. I’m endlessly fascinated by the things my characters try not to say. They lend such tension and dramatic possibility to the narrative, so I can’t promise, even if I set a novel in a large city, that the characters won’t have things they’d rather keep hidden.

Lee Martin will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.