Some Words to the Close and Holy Darkness

A writer explores her enduring ties to a seasonal classic by Dylan Thomas

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This essay originally appeared on December 20, 2019.

***

In terms of genre, Dylan Thomas’ “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” has fallen under numerous categories of description: story, script, essay, poem, sketch. Confusion over defining it makes sense, given that the piece swirls together lyrical interludes of memory, rather than advancing in scenes toward a plot. When it first reached me — during a child’s Christmas in Tennessee — I didn’t know how to define it either. But as great stories sometimes do, “Child” had already begun its work, defining me instead.

“Child” conjures the holiday rituals of the narrator’s boyhood in Swansea, a Welsh sea town. The incidents he describes sparkle with eccentricity and seasonal cheer. But “Child” gains its real power from Thomas’ narrative voice, which bursts with abundance, mystery, and spiritual suggestion. His lyrical prose taught me about the impossible task of truly sharing our most indelible memories. The rich necessity of such experiences leads to inevitable frustration when we try to convey their complexity.

“Child” conjures the holiday rituals of the narrator’s boyhood in Swansea, a Welsh sea town. The incidents he describes sparkle with eccentricity and seasonal cheer. But “Child” gains its real power from Thomas’ narrative voice, which bursts with abundance, mystery, and spiritual suggestion. His lyrical prose taught me about the impossible task of truly sharing our most indelible memories. The rich necessity of such experiences leads to inevitable frustration when we try to convey their complexity.

Early on, he clues us into this trap of memory: “All the Christmases roll down toward the two-tongued sea, like a cold and headlong moon bundling down the sky that was our street; and they stop at the rim of the ice-edged, fish-freezing waves, and I plunge my hands in the snow and bring out whatever I can find.” Thomas offers us each moment as it arises, but the telling remains fragmented and illusory.

My first exposure to “Child” was an hour-long TV special, aired in the late 1980s. This British import arrived in my world context-less, with no literary pedigree attached. Walmart carried no ornaments or wrapping paper featuring the narrator’s encounter with a smoky front parlor and brass-helmeted firemen, or the two windblown Welshmen he watches marching down to the sea, or the moment he lurks at a snowy street corner, munching candy cigarettes. But I was entranced by the story’s world.

Taped from television, our VHS copy grew wonky from overuse. In the process, my drab Nashville backyard became his “white as Lapland” snowscape. My plastic corporatized toys became his wooden tomahawk and battalion of tin soldiers. My usual fleet of aunts and uncles became his — that cast of eccentric singers and tricksters, overfull with holiday bounty and bittersweet hints of their own pasts.

Playing the narrator, Denholm Elliott’s pensive, vulnerable expression passes from rapt joy to sudden grief and back again. His enveloping voice mixes fond remembrance with wry irony, colluding with the viewer, lending scenes of family togetherness or boyhood adventure the tonal depth and range expressed in the story itself.

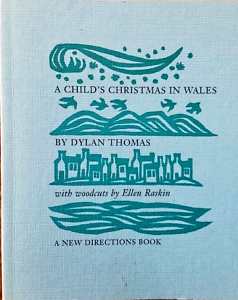

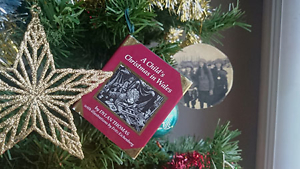

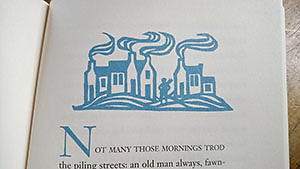

I now own two stylish print versions of “Child” — a tiny storybook sized to hang from a tree branch and a light blue New Directions edition, sleeker and modern in design. The tiny book contains charming wood engravings by Fritz Eichenberg, illustrating key images from the story in rounded, exaggerated detail. The New Directions book features woodcuts by Ellen Raskin. Her woodcuts create a more elemental landscape for the story, opening up more space for readers to conjure images of their own holiday reminiscences alongside Thomas’.

I now own two stylish print versions of “Child” — a tiny storybook sized to hang from a tree branch and a light blue New Directions edition, sleeker and modern in design. The tiny book contains charming wood engravings by Fritz Eichenberg, illustrating key images from the story in rounded, exaggerated detail. The New Directions book features woodcuts by Ellen Raskin. Her woodcuts create a more elemental landscape for the story, opening up more space for readers to conjure images of their own holiday reminiscences alongside Thomas’.

But I might be projecting that intent. Decades on, I’ve never stopped layering my holiday environment onto Thomas’ story, or else absorbing the elements of his story into my own. Each year, when the stresses of the holiday season begin whipping up into frenzy, I weather them by imagining that I’m roaming around the world described in “Child”: the magic of winter, the mysteries surrounding family members and neighborhood haunts, the odd flexes of time when normal schedules are suspended.

As I grew up, pursuing a life among writers and readers, I was startled to learn that literary critics had dismissed the story as sentimental, a mere piece of nostalgia that idealized childhood. Even as an actual child, I never received the story as an idealized portrait. Rather, what seemed clear to me was the narrator’s thwarted attempt to convey the complexity of his memories to another person. At various points in the narrative, his young listener even claims to understand, but the narrator bats away that possibility. Accumulating detail upon detail, he keeps trying to voice the full picture of what he remembers.

From the start, I recognized in him something that was already gathering strength inside me: the drive to tell the stories that matter most, that derive from the innermost core of ourselves. Thomas demonstrates Albert Camus’ assertion that a writer’s life is a “slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” Thomas’ narrator assures me that we may keep on taking some of these detours all our lives.

The Swansea of Thomas’ youth was hit hard by WWII German bombing raids. Many sites he knew and frequented were later destroyed. During the postwar years in which Thomas wrote the various sketches that led to “Child,” wartime losses everywhere around him likely amplified his drive to find a voice for the unreachable past.

To me, the narrator’s childhood is tinged by the darker unknowns that accompany even the safest, most loving childhoods. Thomas may depict a holiday world full of snowy adventures and warm abundance, but its ghostly periphery hums with ancient voices, burns with pagan fires. All town-fed children sense the undomesticated forces that may draw them away from the family hearth and spirit them off, lost to the wild winter’s night.

That danger may also live much closer — in the tired eyes of our parents suggesting the tug of their own vanished childhoods. Or in the unimaginable fragility of our most elderly relatives. In their presence lives a terror we may not be able to name, but which hovers at the edges of holiday gatherings. The glow of familial togetherness in “Child” also recognizes those who live just outside that radiating warmth. In the house, “some small few Aunts, not wanted in the kitchen, nor anywhere else for that matter, sat on the very edges of their chairs, poised and brittle, afraid to break.”

The long dark of solstice season offers grander danger. The narrator slips outside to sing carols with his friends on Christmas night, “when there wasn’t the shaving of a moon to light the flying streets.” The boys approach a stranger’s house down a long drive, “Each one of us afraid, each one holding a stone in his hand in case.” Around them, “the wind through the trees made noises as of old and unpleasant and maybe webfooted men wheezing in caves.” Their fear is so strange, so elemental, that it can summon the primeval past.

The long dark of solstice season offers grander danger. The narrator slips outside to sing carols with his friends on Christmas night, “when there wasn’t the shaving of a moon to light the flying streets.” The boys approach a stranger’s house down a long drive, “Each one of us afraid, each one holding a stone in his hand in case.” Around them, “the wind through the trees made noises as of old and unpleasant and maybe webfooted men wheezing in caves.” Their fear is so strange, so elemental, that it can summon the primeval past.

And when the carolers sing, what do they hear? “A small, dry voice, like the voice of someone who hasn’t spoken for a long time, joined our singing: a small, dry, eggshell voice from the other side of the door: a small dry voice through the keyhole.”

Thomas may pile his descriptions thick, but the style makes sense from someone determined to evoke the whole of his experience — meaning, the whole of all experience. Just as Christmas itself is underpinned by the remnants of its pagan origins, Thomas’ Welsh hillsides and sea towns imbue even the most domesticated moments with a mystical, untamed aspect.

His voice mingles sacredness and wild risk, death and rebirth — the great cycles of our lives. He casts a spell. And all stories of childhood have taught us: When a spell is cast, the rules of our everyday lives bend and shift. New rules apply, and for the time we are under its spell, the story’s world becomes our world.

The holiday season often demands that we succumb to its spells. During those festive weeks, we live according to its rules. Carols blare from every public speaker, unfathomable amounts of seasonal merchandise and decoration suddenly appear, wherever we turn. Whether we welcome this sensory overload or dread its arrival, there’s no denying the holidays’ power to transform our experience and assert the will of its world. For me, weathering the harshest commercialized fuss does not mean refusing it wholesale. Rather, I try to look for that ghostly periphery, to listen for the ancient voices whispering to us from the edges of our noisy, brightly lit modern celebrations.

Just days ago, I sat watching the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, one corporatized seasonal spectacle that I can’t help but love, even as I reach for the mute button now and then. I thought of my grandmothers — one, dead three months ago, and the other still living — both in their nineties. I’ve had decades to absorb their stories deep into my own personal myth, then begin questioning the details and asking them to tell me the stories all over again. I caught myself forgetting that my father’s mother — an unforgettable muse in whose presence my heart surely first opened, Camus-style — is no longer here to be asked.

The following day, my mother’s mother was unable to summon salient pieces of her memory. My mother and I dove into the uneasy silence, helping to tell a story from my grandmother’s girlhood that we both treasure, the story I’d asked to hear again: how, one day on her parents’ farm, she’d panicked and leapt over a pissed-off rattlesnake into her terrified sister’s arms. How they both then watched their eldest sister come bashing into the scene with a shovel, beheading the snake and saving them.

My mother and I blurted out each detail in a disjointed list — a snake rattling in the Alabama dirt, two little girls squealing, a heroic sister raising her weapon above their heads. We grew overeager, perhaps, gripped in our heightened need to prompt her memory. It’s possible we changed history in that moment. Maybe the snake grew larger, or the girls shrank younger, more helpless. We watched her listening to this tale of wonder from her own life, stunned that it had happened, stunned that it had slipped from her mind.

Now I’ve tried to tell you the story, but I know I haven’t come close. I know I’ll have to try again.

Certain veils thin during the holiday season — between old year and new, light and dark, adulthood and childhood. Thomas understood this state of seasonal mind. As the final passage of “Child” winds down, the narrator has run home from that unknowable night and spent a warm evening surrounded by family. He climbs the stairs for bed. He listens to the music playing downstairs among those who love him, who will someday be gone: “I said some words to the close and holy darkness, and then I slept.”

Copyright (c) 2019 by Emily Choate. All rights reserved. Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.