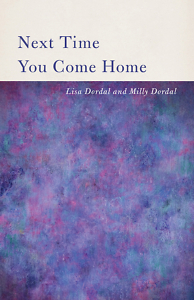

Something Between a Letter and a Poem

Lisa Dordal reshapes her late mother’s letters into poetry

Every family relationship is a work of collaboration, whether a harmonious or fractured one. In 2021, two decades after the death of her mother, Milly, Nashville poet Lisa Dordal unexpectedly found a trove of letters Milly had written to her. This discovery set her reeling. The eventual result of that experience is Next Time You Come Home, a fascinating experiment in how to honor a loved one’s legacy.

As Dordal describes in an introductory essay, a potent wave of grief compelled her to type up the letters, all 180 of them, in order “to spend more time with my mother, and in a more participatory and embodied way.” Soon, however, she began to “distill” the letters into poems, “stripping away text to let the parts I wanted to keep soar, and rearranging text when I wanted to bring out certain tensions between stories or images.” Dordal considers the final versions as “something between letters and poems.”

As Dordal describes in an introductory essay, a potent wave of grief compelled her to type up the letters, all 180 of them, in order “to spend more time with my mother, and in a more participatory and embodied way.” Soon, however, she began to “distill” the letters into poems, “stripping away text to let the parts I wanted to keep soar, and rearranging text when I wanted to bring out certain tensions between stories or images.” Dordal considers the final versions as “something between letters and poems.”

Dordal details her process up front, wisely choosing to disclose the choices she made as she “sculpted” her mother’s prose into poetry. It’s easy to imagine how manipulative such a project might turn in the hands of a less conscientious writer. But Dordal’s smart formal decisions (and transparency) reveal how much she trusts the power of her source material. This trust — backed up by clear, unfussy craft — infuses the collection with a graceful honesty.

Given how complex their mother-daughter relationship was, this respectful sense of authenticity is no mean feat. Dordal’s relationship with her mother had been somewhat fraught, thanks to Milly’s high-functioning alcoholism. Since childhood, Dordal had known two different sides of Milly, which she thought of as “daytime mother” and “nighttime mother.” Milly’s drinking worsened over the years, compromising Dordal’s understanding of who her mother really was.

From Next Time You Come Home, a vivid, engaging portrait of Milly’s perspective emerges. Like many letters between loved ones, hers capture the flow of incidental detail, accumulating over the years. We read her spirited, sometimes wry observations about family members, the books she’s reading, how her church is run, what the baseball scores are. Dordal smartly shapes and orders these snippets of her mother’s voice.

Of particular importance is Milly’s relationship to the natural world, integrated into her everyday life. She mentions her gardening tasks but also notices the details of flowers in various other contexts. She takes special note of the sky’s ephemeral beauties, the weather, and the turning seasons.

Threaded among the everyday detail, however, are certain lines that open the poems up, with sudden aching tenderness: “I’m wearing the gym shoes that you left.” “P.S. I’m using this paper because it’s your color.” “I carry your letter in my purse.” Often appearing at the end of poems, these simple, spare lines make a startling impact. They resonate with a mother’s longing to connect, however she can, over great distance.

Threaded among the everyday detail, however, are certain lines that open the poems up, with sudden aching tenderness: “I’m wearing the gym shoes that you left.” “P.S. I’m using this paper because it’s your color.” “I carry your letter in my purse.” Often appearing at the end of poems, these simple, spare lines make a startling impact. They resonate with a mother’s longing to connect, however she can, over great distance.

Dordal finds numerous ways to contrast the depth of feeling in the letters with lighter fare. In a letter from 1990, Milly writes: “I love the ‘Broken Pitcher’ notecard you sent. / The woman in the painting reminds me of you (and me).” Dordal juxtaposes this with the next lines: “Silly Putty is 40 years old this week. / To celebrate, they are making it in colors.”

Other moments seem to hover outside of time, some mystery intact: “Everyone enjoyed / seeing your pictures, hearing about your life in San Francisco— / the earthquake, the case of mistaken identity.”

Dordal’s opening essay acknowledges certain gaps that exist in the overarching narrative, a by-product of the “distilling” process that remade her letters into poems. Dordal writes that these gaps, as well as the letter/poem hybridity of these works, reflect the miscommunications and reticence that existed in her relationship with Milly. The result is a compelling experience in which pauses or juxtapositions suggest deep wells of unspoken devotion.

“I put the envelope you sent in the top drawer of your dresser. / It feels good to have something in there of yours.”

Sometimes the architecture of Dordal’s craft choices feels purposely exposed. As she pares down and shapes into lean poetry what must have been far longer and more diluted pages of letter writing, an awareness of her hand at work heightens the experience of this collection. Dordal describes the process of making these poems was “one of deep listening,” creating a sense of collaboration. The poems themselves bear out this claim.

Next Time You Come Home becomes a moving testament to the freighted everyday exchanges between mothers and daughters and to the written word’s power to offer new modes of exchange that stretch our perceptions of one another, sometimes even beyond death.

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Mississippi Review, storySouth, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.