Soul Survivor

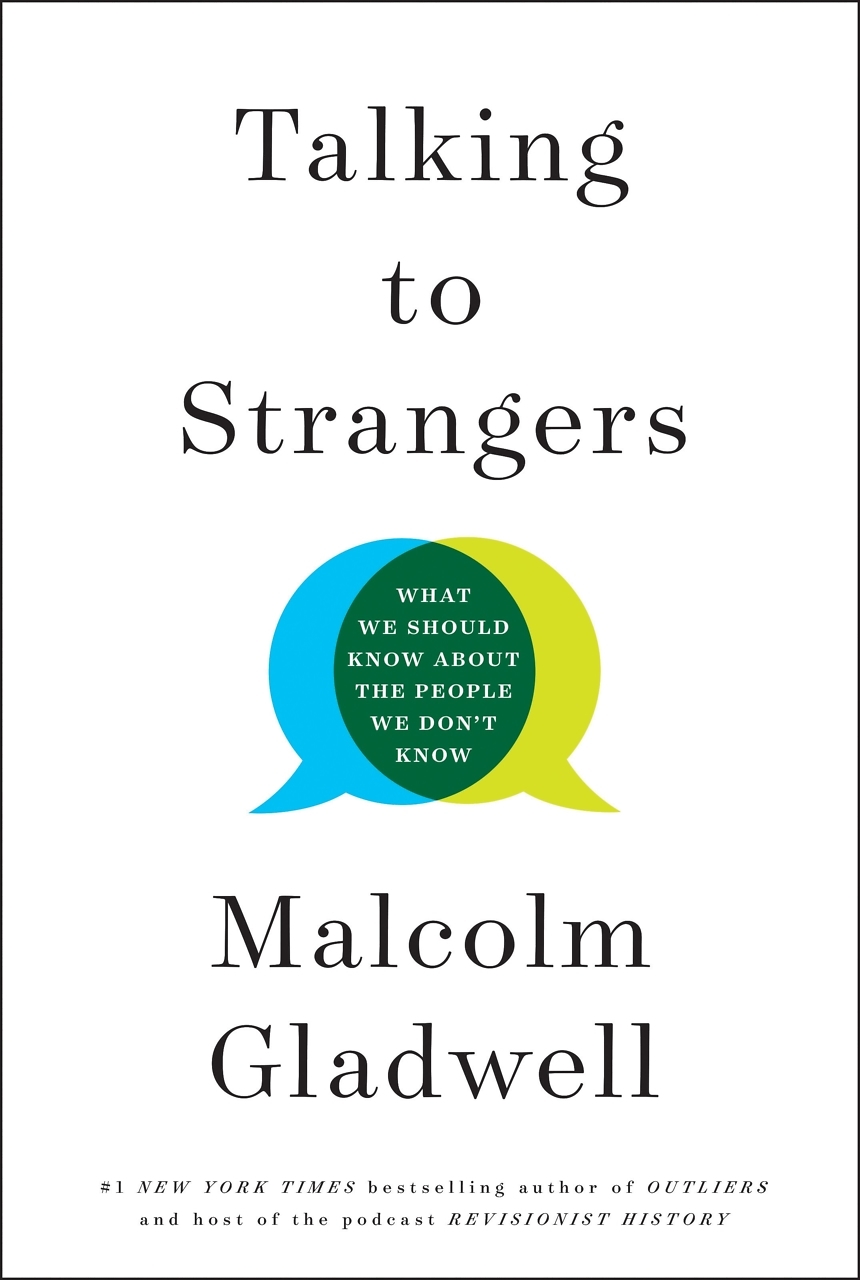

In Every Night’s a Saturday Night, legendary rock ‘n’ roll saxophonist Bobby Keys, best known for his adventures with the Rolling Stones, shines a light on the life of a career sideman

According to Keith Richards, Bobby Keys is “the hottest sax (not to be confused with sex) player on the planet.” Ol’ Keef should know. From the moment Keys laid down his first Stones sax solo on Let it Bleed’s “Live With Me,” his signature sound became an integral element of the Stones’ evolution from the darker, tougher alternative to the Beatles during the ‘60s into the World’s Greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Band. But Keys’s epic musical journey began long before that: when he was a young boy growing up in Slaton, Texas, he finagled his way into the garage-band rehearsals of a lanky, bespectacled high-school kid by the name of Buddy Holly. A few years later, Bobby Keys was on the road with almost too many rock ’n’ roll legends to be named, and in the studio laying down his Southern-fried solos on classic recordings by everyone from Dion and the Belmonts to former Beatles John Lennon and George Harrison. As Rolling Stones sideman and Keith Richards’s sidekick, the name of Bobby Keys became synonymous with the breathtaking highs and scandalous lows of the group’s most celebrated and notorious years.

He has since settled down in, of all places, Nashville—which Keys himself dubs “a saxophonist’s graveyard”—reemerging recently with a new band and regular gigs at local venues like the Mercy Lounge. He can still be relied upon to run through his classic repertoire, burning it up on “Brown Sugar” and “Sweet Virginia” so that fans old and new can hear first-hand the magic that added the American soul to masterpieces like Exile on Main Street and Sticky Fingers.

Perhaps inspired by Life, Keith Richards’s recent memoir, Keys has just produced a surprisingly lucid and detailed account of his hazy whirlwind life on the road and in the studio with so many of modern music’s greats. Written with the assistance of former Nashville Lifestyles editor Bill Ditenhafer, Every Night’s a Saturday Night meticulously traces Keys’s extraordinary rise from the dusty outskirts of Lubbock, Texas, to bear witness to the glory years of rock ‘n’ roll. When Keith and Mick were still schoolboys, Bobby Keys was touring with Bobby Vee and Buddy Holly, learning from King Curtis, getting turned on to pot by Little Anthony’s Imperials while touring with Dick Clark’s Caravan of Stars, and playing (often uncredited) on countless hits.

If Bobby Keys is best remembered for his inimitable playing on the string of albums—Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, and Exile on Main Street—that mark the Stones’ artistic and creative zenith, he is only slightly less notorious as Keith Richards’s wingman in alcoholic, narcotic, and pharmaceutical excess, and Every Night’s a Saturday Night is clearly meant to stand as a defense against any suspicion that he is a party animal first and a world-class musician second.

If Bobby Keys is best remembered for his inimitable playing on the string of albums—Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, and Exile on Main Street—that mark the Stones’ artistic and creative zenith, he is only slightly less notorious as Keith Richards’s wingman in alcoholic, narcotic, and pharmaceutical excess, and Every Night’s a Saturday Night is clearly meant to stand as a defense against any suspicion that he is a party animal first and a world-class musician second.

Though Keys never shies from the facts, he does manage, in his dry, drawling, understated Texan’s manner, to dispel a few myths. He did not, for instance, get kicked out of the Stones for bathing with a groupie in several thousand dollars’ worth of fine champagne. He was merely forced to deduct the cost of the champagne from his salary. Keys and Keith did not intentionally set fire to the bathroom in Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion. They simply placed a towel over a naked bulb to provide a little mood lighting, and were just too stoned to move when the towel caught fire and fell to the equally flammable deep-pile rug.

As for the famous incident in which Bobby and Keith were filmed throwing a television from a hotel window, Keys would like to set the record straight: he and Keith tossed that television out the window at the behest of filmmaker Robert Frank, who wanted more salaciously bad rock ’n’ roll behavior for his tour documentary. (Frank got more than enough of it in the end: the film, Cocksucker Blues, remains embargoed by order of the Stones’ attorneys, who feared that its footage of the Glimmer Twins as they snorted and injected their way across America might threaten the prospect of any future U.S. tours.) “I tell you, if there’s one moment I could take back it would be that moment of throwing that damn television set out the window because, of all the music, of all the solos, of all the records I have played on, out of everything I’ve done in my life that had to do with rock ’n’ roll, that plummeting television set seems to be the most ingrained picture in people’s mind of what it is I do,” Keys writes. “’Oh, you’re the guy who threw the TV set out the window with Keith Richards!’ Yea, but, you know, I also did this and this and this—‘Yeah, but you’re the guy who threw the TV out!’”

Keys isn’t fool enough to claim he regrets having been along for the ride on some of rock music’s most glamorous and luxurious roller coasters. “I always wanted to play rock ’n’ roll and make a lotta money and get a lotta chicks—what the hell else was there to aspire to?” he writes, reflecting on the Stones’ 1972 U.S. tour. “It was just a wonderful time on this planet for Bobby Keys.” Still, Keys doesn’t mind recounting the time he and Keith drank this or smoked that, but would prefer to save his more energetic storytelling for describing the way the solo on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” came about, or the euphoric sensation of taking a smoke break under a tree outside Nellcôte, Keith Richards’s rented French mansion during the Stones’ years in tax exile from England, and listening with wonder as the group worked out the songs that would form their pièce de résistance, Exile on Main Street.

Keys isn’t fool enough to claim he regrets having been along for the ride on some of rock music’s most glamorous and luxurious roller coasters. “I always wanted to play rock ’n’ roll and make a lotta money and get a lotta chicks—what the hell else was there to aspire to?” he writes, reflecting on the Stones’ 1972 U.S. tour. “It was just a wonderful time on this planet for Bobby Keys.” Still, Keys doesn’t mind recounting the time he and Keith drank this or smoked that, but would prefer to save his more energetic storytelling for describing the way the solo on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” came about, or the euphoric sensation of taking a smoke break under a tree outside Nellcôte, Keith Richards’s rented French mansion during the Stones’ years in tax exile from England, and listening with wonder as the group worked out the songs that would form their pièce de résistance, Exile on Main Street.

Readers hoping to learn more titillating details of excess would be better served turning to Richards’s wickedly unapologetic Life or biographer Stephen Davis’s Old Gods Almost Dead. What Keys offers instead is a unique insight into the creative process and experience of a career sideman. His sound is so original that he became, by his own accounting, “the only guy who’s ever split with the Stones and been allowed back in the fold.” Nevertheless, as a sideman, Keys is always on the fringe—dependent on the schedules and whims of his employers, and, of course, always on the periphery of the spotlight. The crowds, the luxury hotels and private jets, the hours in the finest studios playing with the world’s best musicians, the champagne baths and invitations to spend a Lost Weekend with John Lennon and Keith Moon in Los Angeles—all of these things can be taken away just as swiftly as they are given. In the end, all any sideman has, Keys argues, are the next note and the courage of his convictions. “Sometimes you might hit a wrong note,” Keys writes. “But, hell, if I’m gonna play a wrong note, I’m gonna play it with as much conviction as I have. Because that’s rock ’n’ roll.”

Bobby Keys will discuss Every Night’s a Saturday Night at Parnassus Books in Nashville on March 19 at 7 p.m., and at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on March 21 at 6 p.m.