Stand By for a Fighter Pilot

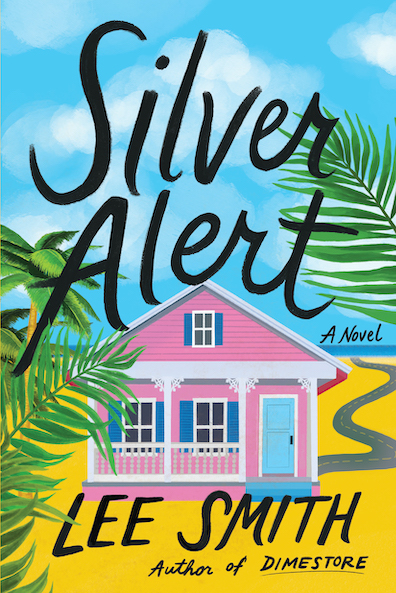

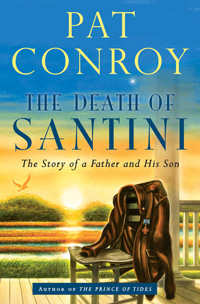

With The Death of Santini, Pat Conroy delivers an emotional farewell to his titanic father

“I’ve been writing the story of my own life for over forty years,” admits Pat Conroy in the prologue to his new memoir, The Death of Santini. “My own stormy autobiography has been my theme, my dilemma, my obsession, and the fly-by-night dread I bring to the art of fiction.” Though he is beloved as a novelist, Conroy’s career began with a well-received memoir: in the The Water is Wide he writes of his time as the teacher of Gullah children on Daufuskie Island (off the coast of South Carolina) during the early 1970s—and of his dismissal for “unorthodox” teaching practices, including the refusal to administer corporal punishment.

Conroy followed this first success with a novel about his childhood. The Great Santini centers on the mercurial figure of his “Thor-like” father: “Because I had studied the biography of Thomas Wolfe with such meticulous attention, I thought I knew all the pitfalls and fly traps into which I could fall by writing on such an incendiary subject as my own family,” Conroy writes in The Death of Santini. But he was unprepared both for the book’s massive success and for the degree of hostility with which it would be met by its subjects. “Nice going, Pat,” his mother told him. “You stabbed your own family right through the heart.” Not long after that, however, the same mother who angrily dismissed her son as “a lousy writer, and a shallow one, too,” was reportedly handing his book to a divorce-court judge as evidence. Similarly, the hardened father who had been brought to tears by the unvarnished portrait of his own tyrannical cruelty was proudly showing up at Conroy’s readings to sign copies. “When I began to write the book, I had never heard the phrase ‘dysfunctional family,’” Conroy explains in the new memoir. “Since the book came out, that phrase has traveled with me as though a wood tick had attached itself to my armpit forever.”

Conroy followed this first success with a novel about his childhood. The Great Santini centers on the mercurial figure of his “Thor-like” father: “Because I had studied the biography of Thomas Wolfe with such meticulous attention, I thought I knew all the pitfalls and fly traps into which I could fall by writing on such an incendiary subject as my own family,” Conroy writes in The Death of Santini. But he was unprepared both for the book’s massive success and for the degree of hostility with which it would be met by its subjects. “Nice going, Pat,” his mother told him. “You stabbed your own family right through the heart.” Not long after that, however, the same mother who angrily dismissed her son as “a lousy writer, and a shallow one, too,” was reportedly handing his book to a divorce-court judge as evidence. Similarly, the hardened father who had been brought to tears by the unvarnished portrait of his own tyrannical cruelty was proudly showing up at Conroy’s readings to sign copies. “When I began to write the book, I had never heard the phrase ‘dysfunctional family,’” Conroy explains in the new memoir. “Since the book came out, that phrase has traveled with me as though a wood tick had attached itself to my armpit forever.”

The Death of Santini is more a career chronicle than a eulogy for the late Marine Colonel Donald Conroy, however. (The actual eulogy the author recited at his father’s graveside is included at the end of the text.) For Conroy’s devoted fans, it will likely become required reading, as the text describes in painstaking and honest detail the origins of many of the characters and events that make up not only The Great Santini, but also The Prince of Tides, Beach Music, and the process of bringing both Santini and The Prince of Tides to the big screen. At its center are the same conflicted emotions that drive Conroy’s novels—chiefly, his love-hate relationships with both his father and his mother.

While his troubled relationships with his parents are ultimately resolved, the central tragedy of the family drama—the suicide of Conroy’s youngest brother, Tom—forms a harrowing hole in which Conroy painfully divulges his own sense of guilt and responsibility for the life of a damaged brother beloved by all but never known well enough to be saved from his madness. “I don’t believe in happy families,” Conroy writes, and by the end of The Death of Santini, we can certainly understand why.

While his troubled relationships with his parents are ultimately resolved, the central tragedy of the family drama—the suicide of Conroy’s youngest brother, Tom—forms a harrowing hole in which Conroy painfully divulges his own sense of guilt and responsibility for the life of a damaged brother beloved by all but never known well enough to be saved from his madness. “I don’t believe in happy families,” Conroy writes, and by the end of The Death of Santini, we can certainly understand why.

Still, the famous rhapsodic lyricism of Conroy’s sentences remains, along with his reverence for the South Carolina low country. Together, in their unmistakable way, these elements pay their own kind of tribute to the complexity of emotions Conroy carries out of the childhood that simultaneously terrorized him and gave him both the tools and the materials to construct some of the best-loved novels of his time. While Conroy is unrelenting in portraying his parents’ flaws and failures, he is equally unreserved in his adoration of their qualities and gifts.

The Death of Santini seems at times an argument for the notion that beauty and terror and love and spite are all intimately intertwined, and that the writer’s duty is not to resolve life’s inherent contradictions and paradoxes but to honor them in all their heartrending intricacy. Conroy wants us to get comfortable with the idea that you can love people who’ve given you good reason to hate them, and that redemption is possible, even for a charismatic, thundering tyrant like Santini, who, in the end, earned himself a “second act,” and became, in Pat Conroy’s eyes, “the best brother, the best grandfather, the best friend—and my God, what a father.”

[This article appeared originally on July 21, 2014. It has been updated to reflect new event information.]

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, is forthcoming from Algonquin Books. He lives in Nashville.