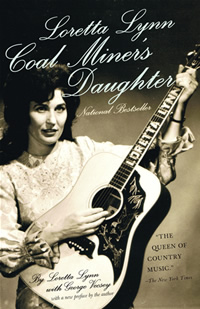

Still Proud to Be a Coal Miner's Daughter

Loretta Lynn talks with Chapter 16 about the reissue of her bestselling memoir fifty years after her first single hit the charts

Loretta Lynn was born in an Appalachian coal-mining community so far from the rhinestones of Nashville there wasn’t so much as a dirt road for getting down the mountain. People entered Butcher Holler, Kentucky, by way of a footpath, and they almost never left.

Loretta did, of course—an exit she credits to her late husband, Oliver Lynn (known to the world as “Doolittle” or “Doo”), whom she married at thirteen. Loretta was still a teenager when Doolittle bought her a guitar for their anniversary, telling her he liked the way she sang to their babies (four by the time Loretta was eighteen). Doolittle was also the one who took Loretta to her first honky tonk and talked the band into giving her a turn on stage.

But Loretta was the one who sang. And Loretta was the one who started writing the songs that spoke to so many women: poor, entirely at the mercy of their husbands, and covered up with babies. She has said she never considered herself part of the women’s movement. Nevertheless, when she sang, in her then-scandalous 1975 hit, “The Pill,” that birth control would let her trade her “old maternity dress” for “miniskirts, hotpants and a few little fancy frills,” her frankness about women’s changing roles had the force of truth spoken to power.

By 1960, she had cut her first single, “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” leaving the kids with her mother and living in the car while she and Doo visited every country-music station they could get to, personally appealing to the disc jockeys to get the record played.

By 1960, she had cut her first single, “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” leaving the kids with her mother and living in the car while she and Doo visited every country-music station they could get to, personally appealing to the disc jockeys to get the record played.

Fifty years later, Loretta Lynn has piled up an Appalachian mountain’s worth of milestones and honors. She has four Grammy awards, sixteen number-one singles, and fifty-one Top Ten hits to her credit, and in 1967 she became the Country Music Association’s first female Vocalist of the Year. In 1972 she hit another milestone, becoming the CMA’s first female Entertainer of the Year. In 1976, her memoir, Coal Miner’s Daughter, became a bestselling book; in 1980, Sissy Spacek’s Oscar-winning performance in the lead role introduced Loretta Lynn—and country music—to an audience far outside the reach of WSM Radio. Six years ago, Lynn recorded the critically acclaimed CD, Van Lear Rose, with rocker Jack White of the White Stripes, further expanding her reach and cementing her success as a music legend.

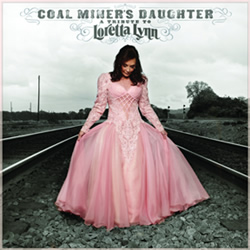

In person, she has the disarming habit of treating every person she talks to like a long-lost friend, even interviewers she’s never met before. Loretta Lynn recently spoke by phone with Chapter 16 about the re-release of Coal Miner’s Daughter and about a new CD called Loretta Lynn: A Tribute to a Coal Miner’s Daughter, arriving November 9, that features today’s country stars—Gretchen Wilson, Lee Ann Womack, Carrie Underwood, Faith Hill, Martina McBride, among others—covering her groundbreaking work.

Chapter 16: A lot of people credit Coal Miner’s Daughter with bringing country music to a larger audience. When you sat down to write the book, did you have any inkling of the impact it would have?

Lynn: I had no idea that anyone would care whether I come from Kentucky, or whether I was born in Kentucky, or whether I was singing or not. I had no idea that anybody would care. I was really shocked when it become one of the bestselling books. It was just a plain little old common book. I didn’t think it amounted to that much, and here it was number one and stayed number one for quite a while.

Chapter 16: What do you think it is that people are responding to in your story?

“Miranda probably says it best. She says, ‘Loretta knocked the doors down so we can go through.’”

Lynn: I think everybody is just about like me. We’re all alike. I think that’s what made it so big. Everybody’s doing the same thing. It wasn’t over nobody’s head. It just got down to the brass tacks. And I think that’s why it’s so big.

Chapter 16: So you still have people coming up to you with their dog-eared copies of the book and asking you to autograph it?

Lynn: Yes, honey: every night that I’m working. They’ll catch me when I get off the bus to go in; they’ll start holding them books up and shaking ‘em. And they have the second book, too. It’s really neat how country music fans are. When they’re with you, they’re with you. I kind of think that country-music fans are even more…they care more than anybody else.

Chapter 16: I just read your new introduction to the re-release of Coal Miner’s Daughter, and you explain that you hand-picked Sissy Spacek for the lead role in the movie.

Lynn: Sissy Spacek, she was the only one that I picked. And I thought that Levon Helm done a great job as my daddy—looked just like him. And you know I couldn’t watch the movie because of that. I seen it the one time, and now I try to dodge it because it brings back so many memories.

Chapter 16: It’s harder for you to watch the film than it was to write the book?

Lynn: Yeah, because it goes much deeper in bad things. I mean, we had nothing when we were growing up.

Chapter 16: Whose idea was it to write this book?

Lynn: I think mine. Believe it or not.

Chapter 16: So you wrote the song first and later realized there was much more left to tell?

Lynn: Right. Because the [recorded version of the song] was only six verses, and I had six verses more. And Owen Bradley says, “Loretta, get in the other room there and take six verses off of that song. There’s already been one ‘El Paso,’ and they’ll never be another one.” And I don’t know what “El Paso” had to do with it, but I imagine it had a lot more verses to it, don’t you? I thought maybe I’d try to listen to that song once I get aholt of it. I don’t know how to get “El Paso” unless you get the Best of Marty Robbins, because he’s the one that had it out.

Chapter 16: Have you ever recorded the longer version of the song?

Lynn: No, I haven’t. I took ‘em off. I don’t know what I did with the six verses, and I can’t find ‘em. I thought I’d go back in and I’ll re-cut this thing. I guess I could go ahead and write six more verses. It won’t be hard to do. But I don’t remember exactly how they went. I remember some of it, but not much.

Chapter 16: You mentioned how hard it is for you to watch the movie. How hard was it to write the book?

Lynn: There would be days it would bother me. It would be according to what we were talking about that day. You know me and Sissy kind of hung together for a year. I kind of stayed with her and made sure that everything was pretty well done like it was supposed to be. I think Sissy had a hard time too because there’d be days where she’d start to cry, and they’d call me on the road and say, “We’re having a hard time with Sissy today. She’s been crying all day, can you call her?” And I would call her. I don’t get to see her much anymore because she’s so busy you know. She come down one day last year, and we did pictures all day long for something that she was doing. I love Sissy, and she knows she can call on me at any time. And I can call on her any time. It’s just one of them things.

Chapter 16: She did an absolutely unbelievable job.

Lynn: She did. She really did. And it really bothered her when she’d start to…. She knew a lot of the stories that went deeper. I think that’s why she’d start to cry. She’d start to remember what we were talking about.

Lynn: She did. She really did. And it really bothered her when she’d start to…. She knew a lot of the stories that went deeper. I think that’s why she’d start to cry. She’d start to remember what we were talking about.

Chapter 16: You’ve written now two memoirs and almost countless songs. Is there a difference between writing a song and writing a life story?

Lynn: Yes, ‘cause the life story you pretty well have to hang to the truth. I mean you don’t want to overdo it or under-do it because it’ll be too emotional if you overdo it, and then if you under-do it you’re not going to get that emotion that you need. It’s kind of hard when you’re writing the truth down. If you’re just making things up, I mean, who cares?

Chapter 16: So your songs are primarily made up?

Lynn: With every song I’ve ever written, there’s a part of me in it. Of course, I’m not going to say what all they were ‘cause it would be hard to even do that, but I know there’s a part of me in every song I’ve wrote, if it’s just half a line.

Chapter 16: In the new introduction to Coal Miner’s Daughter, you mention that you have a writing room beside your house. Could you describe that for me?

Lynn: Tim Cobb kind of set it up. He’s the one that makes all my gowns and stuff. He tries to do stuff like that to help me out, and he fixed up the little writing room ‘cause he knew that I like to go out there and write. I can’t write around anybody. It has to be whoever I’m writing with or be by myself. So he set up the writing room, and Sheryl [Crow] used the writing room the whole time she was here. And Miranda [Lambert] had her bus, so we all three had a place to run to when we got tired of each other. They did “Coal Miner’s Daughter” with me––on the new album.

Chapter 16: Is your writing room a separate little cabin?

Lynn: Yeah, it’s two rooms. They’re pretty big rooms, and it’s a separate thing from the house, so that’s good too.

Chapter 16: Does it have a computer, or do you still write by hand?

Lynn: All by hand. Little Shawn Camp, he writes with me a lot, and he just called a while ago. Left a message: “Hey, Loretta. It’s about time you called me, you know. We need to get back into writing.” So I’ve got to give him a call and tell him to “get back over here, then, if we’re gonna write.”

Chapter 16: Are you working on new songs right now?

“I had no idea that anybody would care. I was really shocked when it become one of the bestselling books. It was just a plain little old common book. I didn’t think it amounted to that much, and here it was number one and stayed number one for quite a while.”

Lynn: Yeah, I’m working on new songs, and that’s what I’m wanting to do—some more new stuff. I’ve got a religious album, and I’m working on a Christmas album. So me and Shawn need to finish up some of the Christmas songs to get them down.

Chapter 16: In Coal Miner’s Daughter, you write that you would sometimes check into a hotel, even when you were back in town, because it was so hard to come home for only a day or two between road trips.

Lynn: Used to, I might be working three weeks and home one day. And this went on for forty years. And people say, “Why are you working so hard?” Well, I worked hard because I had to. I had a big family, and my husband was a mechanic. He didn’t make enough money doing mechanic work to pay the rent, let alone anything else. So it was rough for us. Yeah, I tried to do everything I could to make it better for the family.

Chapter 16: How big is your family now?

Lynn: Twenty-one grandkids. I think there’s two or three great-grandkids. I’m not sure, but there might be a couple. I don’t want to even talk about it. Then I’d have ‘em all here to dinner tomorrow. And that happens, too.

Chapter 16: They all live nearby?

Lynn: Yeah. And you know it’s funny because most of them sing. Tayla Lynn, my little granddaughter, she sings. She’s on the road with a couple other girls [as part of the country trio Stealing Angels].

Chapter 16: I wanted to talk to you a little bit about how things have changed in the business and in town. When you came to Nashville in 1961, your first single, “Honky Tonk Girl,” was already on the charts. Do you think a song like that—or a singer like you—would have the same reception today?

Lynn: I think so. There’s not that much going on out there to this day.

Chapter 16: It’s universal.

Lynn: I think so. Country music gets out a lot better now because of TV. They have the MTV thing, and that helped.

Chapter 16: You’re talking about Country Music Television?

Lynn: Yeah, that helped a lot. But there’s another one [GAC] that plays country music all day long and they’re doing a great job, I think.

Chapter 16: What’s the biggest difference between Nashville now and Nashville when you got here?

Lynn: Well, it’s more open to country music now than it was. It was kind of like a hush-hush thing when I come to Nashville. I couldn’t believe it. They wasn’t no country music hardly at all being played. The Opry was being played; Patsy [Cline] was being played, but Patsy was never real country, and there were very few [others being played on the radio.] Jim Reeves was one of the guys, and Sonny James—I worked with both of them. When we first started, I was in there with ‘em. Jim Reeves borrowed my guitar for one of the shows one day. His got busted. He was doing a movie, and his guitar got busted so he borrowed mine. Doolittle was traveling with me at the time, and he looked over at Doo, and he said, “Doo, why don’t you buy that girl a guit-tar.” He couldn’t keep it tuned; he couldn’t hardly sing with it, so I thought it was funny.

Chapter 16: Did you get a new guitar?

Lynn: Well, I got a new one later on, but not right then. We had to wait till we got enough money to do that.

Chapter 16: You really started your own success by visiting radio stations in person.

Lynn: Radio stations and radio stations. And today, I still talk to [the DJs] on the phone. And if I’m in the town and I’ve got the time, I stop and see ‘em now.

Chapter 16: I’ve heard Taylor Swift started in a similar way, going door to door on Music Row.

Lynn: Oh, did she?

Chapter 16: Do you see yourself in any of the young female country artists today?

Lynn: Miranda [Lambert] reminds me a lot of me. She probably reminds me of me because she likes the honky-tonk songs, and you can’t go wrong with a honky-tonk song.

Chapter 16: She’s on your new record.

Lynn: Yeah, she is. The day that they come down here to work with me, all day long we were so busy recording “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” all three of us; that was quite a lot of work. I ended up working till about nine o’clock that night. We put in a hard day’s work that day.

Chapter 16: And you didn’t have a chance to just chat about what the business is like for them and whether it’s any different from your own experience as a young artist?

Lynn: We never had a chance to do any chatting. I think all three of us knew what the other one was thinking, and they knew that I loved ‘em for what they were doing. I appreciated that so much. And Kid Rock did that [“I Know How”]: “Yeah, I love her/ like she wants me to/ and I know how.…” I cut that, and I cut it real slow and bluesy. Boy, he moved in there and he… [sings] “Yeah, I love her like she wants me to.” I mean, he rocked. It’s great. He did it the other night on that Grammy show. I just thought it was great.

Lynn: We never had a chance to do any chatting. I think all three of us knew what the other one was thinking, and they knew that I loved ‘em for what they were doing. I appreciated that so much. And Kid Rock did that [“I Know How”]: “Yeah, I love her/ like she wants me to/ and I know how.…” I cut that, and I cut it real slow and bluesy. Boy, he moved in there and he… [sings] “Yeah, I love her like she wants me to.” I mean, he rocked. It’s great. He did it the other night on that Grammy show. I just thought it was great.

Chapter 16: The songs on this record are so associated with you—not with just your singing voice, but also with your life. Is it odd to hear other people covering your songs?

Lynn: Oh, it tickles me to death. I don’t think it’s odd ‘cause I cut people’s songs all my life. I just think it’s such a great thing that they cared enough for me to do this. You know, I never thought people cared about me being in the business almost fifty years now. And so I just thought it was fantastic that they cared enough that they even helped me out. That just shows you the country artists. It shows you the difference [between] the country artist and the rest. I think.

Chapter 16: I just re-read Coal Miner’s Daughter, and one thing you don’t really spend a lot of time on is how some of your songs—like “The Pill” and “One on the Way”—were considered controversial. Some of them were even banned from the radio.

Lynn: I didn’t do it to be controversial. I was just cutting about real life, and they banned them at the stations, you know? And I thought, “Why in the world are they banning them? It’s going on all the time.” I never could understand why they’d do that. But every time they banned one, it went number one for me. I didn’t really have to get out and spend any money or work with it. They still record my songs. So I’m just so thankful. Kid Rock, he sang [“I Know How”] the other night [at the Grammy Salute to Country Music]. Was you at the show?

Chapter 16: No; I’m sorry I wasn’t.

Lynn: Well, what happened, Margaret? You should have hollered, and I could have taken you in.

Chapter 16: I wish you had. That would have been a highlight of my life.

Lynn: If you’d’a come out to the bus—I got ready in the bus and everything.

Chapter 16: Next time I’ll try.

Lynn: OK. And when we do shows down here, come down, too. It won’t cost you a thing; you just holler for me. Just say, “Loretta told me to come,” and that’s that.

Chapter 16: I’ll look forward to that. I was just thinking about that song Kid Rock sang the other night: when you first recorded that song, did you ever consider yourself a little bit ahead of your time?

“Life’s life, and everybody lives it the same way. Some of them have a little more money than others; so what? I don’t care if you’ve got money or if you’re poor, you’re going to go through life about the same way.”

Lynn: I thought, “It’s weird that they’re banning them because everybody’s living this.” I was writing about my life, and everybody around me was living about the same way. I never could understand why they’d do that. I guess it was because they were a little bit… like they didn’t want nobody else to know. That’s ridiculous. Life’s life, and everybody lives it the same way. Some of them have a little more money than others; so what? Everybody has to live the same way. I don’t care if you’ve got money or if you’re poor, you’re going to go through life about the same way.

Chapter 16: Do you think it’s easier or harder today for a country artist to sing about controversial topics?

Lynn: Oh, it’s easier. Oh, yes. Because this was fifty years ago that I was doing it, and I think maybe I knocked down a few of the doors. Miranda probably says it best. She says, “Loretta knocked the doors down so we can go through.”

Chapter 16: Better than just opening the doors—just flat-out blowing them off the hinges.

Lynn: It’s true. Where do you live, Margaret? Are you in Nashville?

Chapter 16: I am. I’m right here in Nashville.

Lynn: Well, great. Then it won’t be no big deal for us to get together.

Chapter 16: I was hoping your publicists would let me come out there for this conversation, but I understand that you’re just really, really busy.

Lynn: Hey, I didn’t know that.

Chapter 16: They’re protecting you, and that’s their job.

Lynn: Well, protecting me from what?

Chapter 16: Being over-committed.

Lynn: Well, [my daughter] Patsy worries about it, and I told her, “Patsy, I’m used to working. I’ve done it all my life; I’ve worked hard––and I’d rather work than not work.”

Chapter 16: You’ve written so many songs about strong women and women who are able to take a hard situation and somehow come out on top, and yet were never associated with the women’s movement.

Lynn: Well, I never had time really. When all this was going down, I was writing about it, but I never really got to live the way that…. Like “The Pill”: you’ve taken it, and you know that other women are taking it, so why make a big deal out of it? And “One’s On the Way”—how many have one on the way? It’s just no big deal, and that’s the way I felt when we was recording them. And when they’d hit the stations, “Well, oh my. One’s on the way, it’s gotta be dirty.” That’s just what their thinking was.

Chapter 16: I’m wondering if one of the reasons you didn’t necessarily consider yourself a feminist or part of that crowd is because your songs were doing all that talking for you.

Lynn: Yeah, I was living through my songs, too. That’s why they were hits. Every woman was living through them songs. And I’ve had ‘em holler out in the middle of my show and tell me all about their life. And sometimes [they] just stand up and start telling about their life. And that’s neat. I think it’s more personal because I would meet ‘em, and we’d talk about the way we had to be living. And not all songs do that.

Lynn: Yeah, I was living through my songs, too. That’s why they were hits. Every woman was living through them songs. And I’ve had ‘em holler out in the middle of my show and tell me all about their life. And sometimes [they] just stand up and start telling about their life. And that’s neat. I think it’s more personal because I would meet ‘em, and we’d talk about the way we had to be living. And not all songs do that.

Chapter 16: You mention in the new introduction to Coal Miner’s Daughter that you don’t even think of them as your fans; you think of them as your friends. Maybe they think of you as their friend, too.

Lynn: Most of ‘em are, and I can have conversations with ‘em, no matter if they just come out one time to see me. As long as they know what I’ve been doing and they’ve been buying the records––well, we know each other. I don’t know their personal lives like they do mine, but I feel like we’re close because we’re talking about people that’s living life. And we’re all the same; we ain’t no different.

Chapter 16: Is there a song you’ve written that you wish somebody would cover because it didn’t get quite the attention you thought it might or hoped it would?

Lynn: I can’t think of one right off the top of my head. If I think of one, I’ll call you back. This is awful, ain’t it?

Chapter 16: I think it’s a good sign! Your last album, Van Lear Rose, was a huge hit with critics.

Lynn: Jack White did that.

Chapter 16: Do you think you’ll work with him again?

Lynn: I think so. I love Jack White. The first time I ever met Jack, my manager, Nancy [Russell], brought him down. I don’t know if you know Nancy or not.

Chapter 16: I don’t.

Lynn: She lives in Nashville. And she’s Alan Jackson’s manager, too. She’s really a sweet person. And she brought Jack down. That’s how we met.

Chapter 16: Do you think his involvement with the project brought your work to the attention of a different audience?

Lynn: I think so, because Jack was a rock and roller. And everywhere I go there’s people there that knew Jack White that bought the album but never bought an album of mine. And I think that helped me a lot. I think Jack White was good for me.

Chapter 16: I think you were good for Jack White, too.

Lynn: Well, we try. We try.

Chapter 16: You’ve written another memoir, Still Woman Enough, and in the new introduction to Coal Miner’s Daughter, you hint that there might be another film. Is that in the works?

Lynn: I think if I want it to be. I think if I work hard and want it…really work at it. I wouldn’t want to just go in and slam one down and say, “Hey, this is another film.” I’d want it to be a hit, just like Coal Miner’s Daughter.

Chapter 16: I was thinking about you during all this excitement in the news about the miners down in South America.

Lynn: It breaks my heart when I hear stuff like that.

Chapter 16: When you hear about these things on the news, does it take you back home?

Lynn: It takes me right back to seeing Daddy come out of the coal mine, just covered with coal dust. And then they’d stop and they’d take a bath—they had bath houses for the miners—and it just took me right back to seeing Daddy come out of the mines. And Daddy would jump me for being around where I could see him because he’d say, “You know it might not be me that comes up out of that mine; it might be somebody that you wouldn’t want to be around.” And daddy would jump me. But I never was afraid. I guess it was a good thing that I wasn’t afraid because I don’t think there was any miners that would hurt me anyway. Because they were all like Daddy. Yeah, the coal miner’s daughter remembers a lot.

Chapter 16: Is there anything I didn’t ask you that you’d like to talk about?

Lynn: I wished you hadn’t-a asked me that. Well, I’ll tell you, you can call me, or you can call Tim, either one. Tim will be happy to help you, too. What we can’t think of right now and you want to know about it, you just call back. Of course, Tim [Cobb], we’re so close, him doing my clothes, my gowns and everything. He has for twenty five years—maybe longer.

Chapter 16: It’s a blessing to have somebody like that—somebody you can trust.

Lynn: It really is. This is the main thing. Somebody that you can trust and you know ain’t gonna hurt you in any way. That’s almost unheard of.

Lynn: Anytime you want to call me, just pick up the phone.

Chapter 16: I will.

Lynn: You know my number.

Chapter 16: I do.

Lynn: Okay, honey.

Chapter 16: Thank you so much.

Lynn: Well, I love you. Bye, bye.