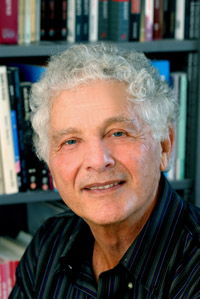

For centuries, the King James Version of the Bible influenced the way Americans understood literary style. In his bookPen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible, Robert Alter explores the myriad ways this seminal work of literature has inspired writers with its simple but vivid diction and egalitarian syntax. Challenging the typical academic focus on discourse and ideologies, Alter considers the KJV from the perspective of style—the “magic of language,” in which words create the alternate realities that challenge the prevailing narratives of the day: “The play of style in fiction is not only a source of deep pleasure, sometimes rapture, but also a process that enables thought, inviting perception of complex associative links,” he writes. For Alter, literary style is what enables readers “to see one frame of meaning in connection with another.”

With the King James Version as its touchstone, Pen of Iron delves into the works of six great American authors, from Herman Melville to Cormac McCarthy, parsing each writer’s ambivalent relationship to the Biblical rhetoric of their day. A book for readers and writers as much as for scholars, this work explores how it permeates our thoughts and speech even as literacy and religiosity change, proving that good style in any genre can be timeless. Prior to his appearances on November 10 and 11 at the 1611 Symposium in Memphis, Alter answered questions from Chapter 16 via email about the Bible, American prose, and his fascination with “the fundamental fact that a set of texts rendered in English four hundred years ago can still fire the imagination of writers who differ extremely from each other and from the Bible.”

Chapter 16: Your book, Pen of Iron, explores the various ways the King James Version and its assimilation into American speech shaped the styles of Herman Melville, William Faulkner, Saul Bellow, Ernest Hemingway, and Marilynne Robinson to name a few, but you acknowledge that the influence of the King James Version style has faded. What is lost, in your view, by this change?

Alter: What is lost as the influence of the KJV fades in American writing is a powerfully resonant dignity in prose style that favors understatement, terseness, and a kind of homespun decorousness.

Alter: What is lost as the influence of the KJV fades in American writing is a powerfully resonant dignity in prose style that favors understatement, terseness, and a kind of homespun decorousness.

Chapter 16: Is there a particular essence of the style of the KJV—or its effect on the reader—that is passed down through American prose?

Alter: I don’t believe that the effects of the KJV can be reduced to a single “essence.” Different writers have taken away different things from the KJV—for Melville, it was the power of biblical poetry; for Hemingway, the parallel syntax and the attachment to plain language; for Faulkner, certain key biblical terms around which he organized his vision of history and human life.

Chapter 16: A recurring stylistic choice in the KJV and many of the works you discuss is the use of parataxis: “The artfulness of biblical parataxis is precisely in its refusal to spell out causal connections, to interpret the reported narrative data for us.” How is the linking of events and details through “and…and…and” particularly useful for American writers and readers in a post-modern world?

Alter: The idea that there might be some connection between biblical parataxis and the post-modern condition is quite interesting. The more predominant form of English syntax, which spells out interconnections through subordinate clauses and explanatory qualifications, may assume a certitude in the grasp of causation and the making of distinctions that at this point in history many writers no longer feel. In that context, the use of parataxis, where connections are left unstated and ambiguous, may be especially congenial to some writers.

Chapter 16: You are also a translator, one who according to one critic, has taken on “one of the most ambitious literary projects of this or any age,” by translating the entire Hebrew Bible. Scholars, critics, and clergy love your translation for its poetic style and ability to capture the character of the Hebrew prose. Did your work as a translator inform your understanding of the legacy of the King James Version in the literary style of future writers?

Chapter 16: You are also a translator, one who according to one critic, has taken on “one of the most ambitious literary projects of this or any age,” by translating the entire Hebrew Bible. Scholars, critics, and clergy love your translation for its poetic style and ability to capture the character of the Hebrew prose. Did your work as a translator inform your understanding of the legacy of the King James Version in the literary style of future writers?

Alter: Working as a translator of the Bible has paradoxically increased both my admiration for the KJV and my reservations about it. The grandeur of the seventeenth-century translation and, at least in the prose, its adherence to the wonderful simplicity and concreteness of the original, have become more vividly clear to me. At the same time, as I look over my shoulder at my fellow-translators of four centuries past, I am sometimes exasperated with them for deploying wordiness where the Hebrew is beautifully compact, for ignoring the expressive rhythms of the Hebrew poetry, and for introducing ecclesiastical terms alien to the original.

Chapter 16: As part of the 1611 Symposium, you will appear with scholars from the United States and England who study the effects and uses of the King James Version of the Bible by very diverse cultural communities. How does a book published in 1611 that comes out of a particular social world become so wildly embraced by radically different communities?

Alter: Great writing by and large knows no cultural borders. I have read that Shakespeare has enjoyed great popularity in Chinese translation, and in Japan, Kurusawa’s film adaptations of Macbeth and King Lear, transposing them into samurai culture, are quite brilliant. For this reason, it doesn’t surprise me that a stylistic achievement as great as that of the KJV should resonate across the globe, wherever people can read English.

Chapter 16: What is most interesting to you about the use or legacy of the King James Version today?

Alter: I suppose what is most interesting to me is the fundamental fact that a set of texts rendered in English four hundred years ago can still fire the imagination of writers who differ extremely from each other and from the Bible. Thus, the late Mississippi writer Barry Hannah wrote about a world of violence, dead-ended lives, and sexual perversity and bleakness, yet he attested in a radio interview a few years before his death that the shaping influence on his prose was the KJV, whose rhythms and syntax he internalized in the Baptist church in which he was raised.

Robert Alter will speak on “The King’s James Bible and the Question of Eloquence,” the keynote address at the 1611 Symposium, on November 10 at 6 p.m. in University Center on the University of Memphis campus. He will also offer a response to symposium speakers on November 11 at 1 p.m. in Blount Auditorium at Rhodes College in Memphis.

Tagged: Nonfiction