Still Running

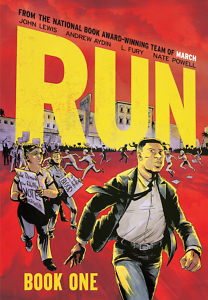

The team behind John Lewis’ March launches a new series

“Progress never moves in a straight line,” writes Andrew Aydin, a longtime policy advisor to the late Rep. John Lewis, in his afterword to Lewis’ posthumous graphic memoir, Run: Book One. “Too many people did not understand the forces that gathered to attack and weaken the Voting Rights Act almost immediately after its passage.”

Aydin previously collaborated with Lewis and artist Nate Powell on the bestselling trilogy March, which began with Book One in 2013 and culminated with Book Three in 2016 — the last volume winning a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. As Aydin explains, Lewis’ team decided in 2017 to build a second series around a “simple” idea: “First you march, then you run.”

Aydin previously collaborated with Lewis and artist Nate Powell on the bestselling trilogy March, which began with Book One in 2013 and culminated with Book Three in 2016 — the last volume winning a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. As Aydin explains, Lewis’ team decided in 2017 to build a second series around a “simple” idea: “First you march, then you run.”

Even before a global pandemic and Lewis’ death, at 80, in June 2020, publication of this new book saw several delays. Now, with the addition of artist L. Fury to the original team, Lewis’ complicated story picks up where the March trilogy left off: The civil rights movement in general, and more particularly Lewis’ Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “SNICK”), has come under attack — not only from external forces seeking to undermine the 1965 Voting Rights Act, but also from internal division, as leaders like Stokely Carmichael and Jim Forman begin to turn away from the nonviolence advocated by Lewis and his mentor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

These divisions roil from the Watts riots to Vietnam War resistance, from embassy protests against South African apartheid to an all-night debate over the future of SNCC at an old church camp in Kingston, Tennessee. A speech in June 1966 by Willie Nicks, a “brash and aggressive” organizer from Chattanooga, introduces a pervasive slogan, “Black Power.” Lewis meets with President Lyndon Johnson and leaders of the Democratic party while other SNCC members advocate violent revolution. Lewis, the lifelong advocate of “good trouble,” wrestles with the question of how “good” his work has become in such a turbulent period of American history.

Ultimately, history is what Run: Book One records as the life of John Lewis becomes increasingly public. As with the first three books, the cinematic artwork that keeps the story moving is painstakingly drawn from photographs and other historical references. (Fury details this process in an informative “From the Artist” essay in the book’s extensive back matter.) While the story remains visually gripping through scenes of sometimes disturbing violence and increasing political intrigue, new realities of the future congressman’s life introduce — out of necessity — a much larger cast of characters than appeared in books of the original trilogy. Readers may find themselves referring to a helpful 12-page “Biographies of the Movement” section ahead of the book’s thorough notes and sources.

These people and their actions allow readers to encounter (many, perhaps, for the first time) the angry divide that existed in America in 1966. “And today the attacks on voting rights continue and bear an all-too-familiar pedigree,” Aydin writes in his afterword, “like those Congressman Lewis faced in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and elsewhere during the early days of the Civil Rights Movement.” Yet it is not those attacks, nor the internal battles of SNCC, that make the book a moving story of one man, rather than a historic account of a movement. As with most good memoirs, and novels for that matter, the book’s greatest conflicts are internal.

“… I could feel everything slipping away,” Lewis says to himself in a poignant panel near the end of Run: Book One. How the 26-year-old regains his life and wins back the movement that he considers his “family” emerges as a driving force behind the new series. In a 2016 interview with Chapter 16, Lewis drew on his experience in advising young protestors to “make our country and our institutions a little more human. It’s not one that lasts for a few days or a few weeks or a few months or a few years — or one election cycle. It is the struggle of a lifetime.”

“… I could feel everything slipping away,” Lewis says to himself in a poignant panel near the end of Run: Book One. How the 26-year-old regains his life and wins back the movement that he considers his “family” emerges as a driving force behind the new series. In a 2016 interview with Chapter 16, Lewis drew on his experience in advising young protestors to “make our country and our institutions a little more human. It’s not one that lasts for a few days or a few weeks or a few months or a few years — or one election cycle. It is the struggle of a lifetime.”

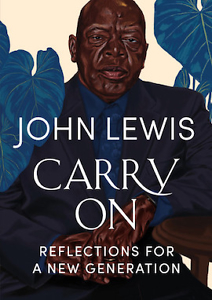

In early 2020, when he knew he was dying of pancreatic cancer, Lewis agreed to write — or rather, dictate — one more book on his philosophy of nonviolent struggle, aimed at young people seeking social justice today. This book was released by Grand Central Publishing in July under the title Carry On: Reflections for a New Generation. In it, he speaks simply and directly of the lessons in nonviolence he learned amid the chaos of the 1960s. In Run: Book One, readers watch as he lives through them.

Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves. He chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas.