Strange Bedfellows

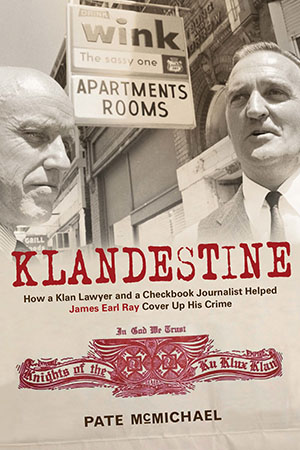

Pate McMichael talks with Chapter 16 about Klandestine, the story of an unlikely partnership that led to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

When Martin Luther King Jr. stepped onto the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968, and got shot by James Earl Ray, it shook the nation and the world. It led to cries of grief and explosions of rage, including riots in a host of American cities. It led to fears that the civil-rights movement, as shaped by King’s philosophy of nonviolent direct action, was over. It also led, we must also remember, to smug satisfaction or indifferent shrugs from a wide swath of Americans.

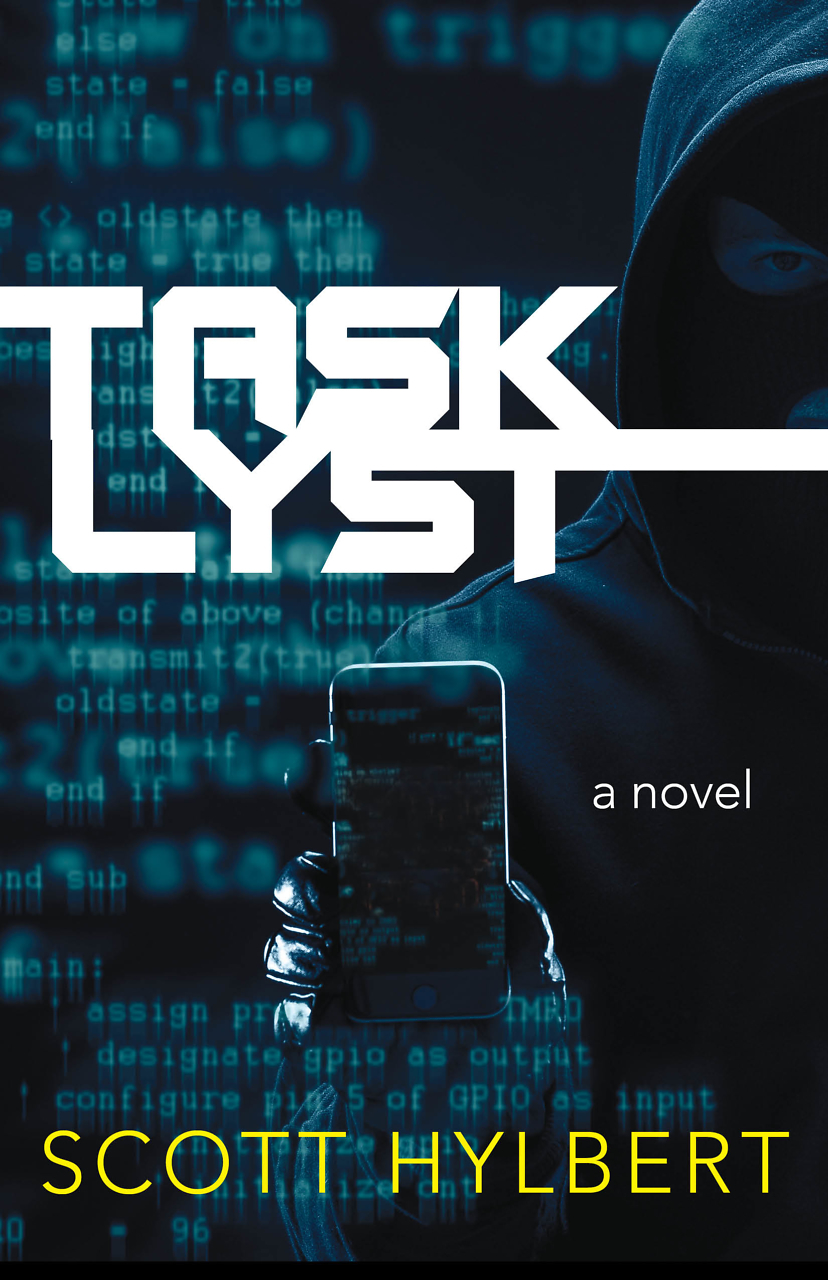

The assassination generated conspiracy theories, too. James Earl Ray did not, at first glance, seem like a foaming-at-the-mouth white supremacist, and soon a tale developed that fingered a blond-haired Latino named “Raoul” as the killing’s architect. In his new book, Klandestine: How a Klan Lawyer and a Checkbook Journalist Helped James Earl Ray Cover Up His Crime, Pate McMichael crushes this myth. Combining rigorous archival research with a fast-paced narrative, he unearths new details about James Earl Ray on the road to Memphis and explains how this particular conspiracy theory arose.

McMichael recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In Hellhound on His Trail, Hampton Sides frames the story of the King assassination around the central figures of James Earl Ray and Martin Luther King. Your narrative, by contrast, revolves around a Klan lawyer named Arthur J. Hanes and a writer named William Bradford Huie, who engaged in the ethically dubious practice of “checkbook journalism,” or paying sources for interviews. Why did you focus on these two characters?

Chapter 16: In Hellhound on His Trail, Hampton Sides frames the story of the King assassination around the central figures of James Earl Ray and Martin Luther King. Your narrative, by contrast, revolves around a Klan lawyer named Arthur J. Hanes and a writer named William Bradford Huie, who engaged in the ethically dubious practice of “checkbook journalism,” or paying sources for interviews. Why did you focus on these two characters?

Pate McMichael: They tell an intriguing story. Together, Hanes and Huie provide two amazing perspectives to understand the legacy of violent resistance to civil rights. Yet neither man has been the subject of a biography.

They were strange bedfellows. Huie had been paying racist killers since the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. He wrote several books about racial violence, including Three Lives for Mississippi. Hanes became famous serving as mayor of Birmingham during the Project C demonstrations of 1963. Kicked out of office by moderates, he started defending racist killers for the United Klans of America. Despite opposite views on race, Hanes and Huie shared a desire for riches and national attention. In the summer of 1968, they forged a lucrative publishing deal to fund Ray’s defense. Selling conspiracy in the King assassination seemed like the perfect bargain until Ray chickened out and pled guilty.

Chapter 16: Klandestine makes an effective case that to understand the King assassination, you need to trace the story to Birmingham, Alabama. Why has the Birmingham dimension received so little previous attention, and why is it so important?

Huie claimed to be in the truth business, but business was more important than truth.

McMichael: Clearly, Ray and Hanes didn’t want anyone looking too closely at Birmingham, a city scarred by dozens of unsolved racial bombings. Instead, they played up Ray’s aimless travels from Canada to Mexico, his interest in locksmithing and pornography. They couldn’t explain Birmingham because Ray’s presence there spoke to his racial motive. It was the place where he purchased the murder weapon and the infamous white Mustang. Then, when finally captured in London, Ray calls for Hanes, a Birmingham attorney who just happens to be the official lawyer for the United Klans of America.

There’s more. I discovered new evidence that Huie thought Ray was connected to a fantastic Birmingham conspiracy with links to the Bay of Pigs. Without giving too much away, Klandestine shows that Huie quietly pursued the possibility that Hanes, who helped recruit pilots for the CIA, was involved in King’s assassination. Ray purchased the murder weapon across the street from the Birmingham airport, where Hanes and the pilots were first approached by the CIA. Birmingham’s role in the Bay of Pigs gave Huie fits.

Chapter 16: How should we judge William Bradford Huie? On one hand, he helped unearth and publicize notorious crimes during the era of the civil-rights movement. On the other hand, he flouted the ethical standards of journalism and engaged in some questionable self-promotion.

McMichael: Huie claimed to be in the truth business, but business was more important than truth. Klandestine shows that he did more than flout ethical standards; he made stuff up. Many historians have accepted his work as truth, but further scrutiny will reveal more inaccuracies and fabrications. In Huie’s defense, the weapon of libel meant that he could not call someone a killer after they’d been freed by an all-white jury. So to eliminate legal risks, he paid killers like Ray to sign contracts that gave him the right to embellish stories, invent dialogue, and take shortcuts that better journalists can’t afford to make. It’s a shame he didn’t just stick to the facts. So much of what we think we know about the Klan came from his pen. He was fearless.

Chapter 16: You detail the construction of one conspiracy theory behind the King assassination, in which James Earl Ray was framed by a mysterious character named Raoul. We encounter conspiracy theories in connection with a great many other tragedies, as well, such as the JFK assassination and the September 11 attacks. What explains this widespread fascination?

Chapter 16: You detail the construction of one conspiracy theory behind the King assassination, in which James Earl Ray was framed by a mysterious character named Raoul. We encounter conspiracy theories in connection with a great many other tragedies, as well, such as the JFK assassination and the September 11 attacks. What explains this widespread fascination?

Pate McMichael: It’s kind of a baptists-and-bootleggers phenomenon. The First Amendment allows us to sell conspiracy, even when the facts prove otherwise, even when we don’t believe it ourselves. That opens the door for dangerous people (bootleggers) to exploit grief-stricken citizens (baptists) in dangerous ways. Big crimes deserve big culprits. We don’t want to believe that a two-bit crook like Ray can so easily kill a great man like King. We don’t want to believe that a zealot like Osama bin Laden and nineteen hijackers got past the FBI, CIA, and NSA. The devil needs to fit the crime.

Klandestine shows how New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (who in 1967 claimed to have solved the Kennedy assassination) provided the template that Ray used to create Raoul, an international mystery man supposedly behind both the Kennedy and King assassinations. Garrison and Ray gave a lot of people what they wanted: the holy grail of a conspiracy as big as John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. History is replete with similar opportunists.

Chapter 16: You have a B.A. in history and an M.A. in journalism. Do you see shortcomings in the work of academic historians? What in particular can journalists contribute to an understanding of the past?

McMichael: I wish academic historians focused more on storytelling. To reach the common reader, you have to tell a story, and you can’t do that taking a comprehensive approach to history. That’s why I focused on Huie and Hanes, rather than rehashing the assassination investigation and every possible conspiracy. I saw a story and tried to tell it as accurately as possible.

I wish academic historians focused more on storytelling. To reach the common reader, you have to tell a story, and you can’t do that taking a comprehensive approach to history.

Don’t get me wrong: I value academic historians because they protect the historical record through rigorous accuracy and attribution. Narrative journalists (like Huie) are notorious for not being accurate when it counts, so I understand the bias that some historians hold against writers with my background. Good nonfiction should marry the two approaches, I believe. It shouldn’t matter how many degrees you hold. Just tell a good story, get the facts straight, and cite the best sources possible.

Chapter 16: The ideology of the Ku Klux Klan is more discredited than ever, yet race obviously continues to shape our current politics and culture, from Ferguson to the White House. What applications might your book have for how people think about race in contemporary America?

McMichael: I hope it will help a lot of Southerners learn how racial hatred sabotaged our entire democracy—from the voting booth to the jury box. Refusing to acknowledge the dangerous history of racial violence and its poisonous role in our political system will only lead another generation down the same path. It comes down to your willingness to bear witness to what happened. Good people looked the other way for too long. Willful ignorance can be a form of bigotry.

Nobody can grow up in the South—or anywhere else for that matter—and not inherit racial prejudice. It’s not possible. Writing this book helped me understand that. I no longer judge other people by the actions of their worst representatives. I also don’t begrudge greatness and truth just because it comes from someone who doesn’t look like me. Dr. King saved us from ourselves. As a citizen of this country, his wisdom belongs to me, not just the black community. His death was a crime against America, not just black America. So racial injustices that plague us today are injustices against all of us. We are all responsible for acknowledging them as such.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.