Strategies for Survival

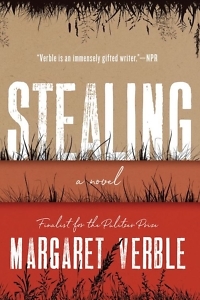

Margaret Verble’s Stealing weaves a tapestry of pain and resilience

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on February 6, 2023. The post has been updated with new details for the paperback edition.

***

My high-school choir in Chattanooga had a repertoire of a cappella spirituals that cleaved the baritones from the tenors, the gifted from the perpetually off-key (raises hand). Among them was “Steal Away,” popularized by Nat King Cole: Steal Away, steal away, steal away home / I hain’t got long to stay here. That archaic usage of the verb “steal” — moving surreptitiously, behind the scenes — informs Margaret Verble’s captivating, subtly crafted novel, Stealing, which recounts one difficult girlhood in Oklahoma in the 1950s.

Nine-year-old Kit Crockett may have a conflicted inner self — her father’s a descendent of Davy Crockett while her late mother was a Cherokee, or “Civilized Indian” — but we wouldn’t know it. With fishing pole balanced on her shoulder, “snake stick” in hand, she strides confidently through grassy fields and creek bottoms, catching and frying up catfish for her daddy. Both parent and daughter are close to their Native relatives, particularly the commanding Aunt Rosa. Each week Kit walks down her dusty lane to the highway, where Miss Francis’ bookmobile rolls up with a robust menu of Nancy Drew and Dr. Dolittle. There’s a touch of Scout Finch in this child’s forthrightness and love of the outdoors, her blazing curiosity.

The Crocketts live along the fringes of poverty, but it’s Paradise to Kit until her Uncle Joe, a World War II veteran and alcoholic from the Native side of her family, is brutally murdered: her first clue that sorrow is the blight man is born for. (A couple of trials recall the courtroom episodes in To Kill a Mockingbird.) After Joe’s death, a beautiful, mysterious divorcée named Bella takes over his dilapidated cabin, gardening and raising chickens and guineas, bankrolled by the wallets of two boyfriends whose cars Kit sees parked outside but whom she never meets.

Bella may be a fancy woman, but she’s compassionate and discerning, blessing the motherless girl with sweet tea and affection. They spend languid afternoons poring over the Sears Roebuck catalog. The girl’s besotted:

I inspected her clothes on the line. There wasn’t a wind, so they weren’t flapping and blown out … Mama’s underwear was sort of square, and had been handmade. But Bella’s drawers were skimpy, and the leg holes were like half moons in their cut. Her slips had lace on the tops, but Mama’s were scooped-necked and plain.

Not all Bella’s neighbors look on her as kindly. Gifted with foresight, the girl senses her new friend is in danger.

Kit narrates Stealing as a 12-year-old, in the wake of tragedy, confined to a religious school for troubled boys and girls. The students at Ashley Lordard are a mix of Indian and white, and Kit suffers beneath the stern rebukes of her teachers and the sexual sadism of the head, Mr. Hodges. She crouches in her closet, scribbling a memoir about that idyllic summer and the dark mystery that brought her to the school. Verble deftly metes out her story in intriguing bits, like a puzzle; Kit likens her dilemmas to jigsaw pieces that don’t lock together. Verble masters the conversational cadences of first-person singular much as Elizabeth Strout does in her Lucy Barton novels.

Kit narrates Stealing as a 12-year-old, in the wake of tragedy, confined to a religious school for troubled boys and girls. The students at Ashley Lordard are a mix of Indian and white, and Kit suffers beneath the stern rebukes of her teachers and the sexual sadism of the head, Mr. Hodges. She crouches in her closet, scribbling a memoir about that idyllic summer and the dark mystery that brought her to the school. Verble deftly metes out her story in intriguing bits, like a puzzle; Kit likens her dilemmas to jigsaw pieces that don’t lock together. Verble masters the conversational cadences of first-person singular much as Elizabeth Strout does in her Lucy Barton novels.

Stealing is a stylistic departure from Verble’s previous When Two Feathers Fell from the Sky, pared down compared to that book’s rich, carnival textures, but Stealing is the more resonant work, as Verble toggles between Kit’s present and recent past. The chapters are short yet tight, weaving delicate threads into a tapestry of pain and resilience. The grim routines at Ashley Lordard unexpectedly shift when a pair of sisters arrive: Are they Comanche, Cherokee, Chickasaw, or Creek? Kit and her friends are keen to figure how they fit in. “The teachers and Mr. Hodges don’t know how different Indians feel about each other and don’t realize we have to learn about each other like we have to learn to multiply and divide,” she observes. “We’re not natural allies, but we’re getting to be that way.”

Beneath the deceptively casual surface of Stealing, Verble is probing a horrific tale: the institutionalization of Native children. (David Treuer’s nonfiction opus, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee, is essential reading on this topic.) Many never came out of the system. Others were forever wrested from their families. As Kit notes, “Really, there are hardly any thieves around here, unless you count Mr. Hodges and the other people who are stealing our lives.” Here Verble reverts to the more common usage of the verb, appealing to our collective moral responsibility. As Kit devises fresh strategies for survival, Verble keeps us guessing: How will this all end? Beautifully written and paced, Stealing is an invaluable contribution to a crucial — and too often repressed — history that haunts us still.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for O, the Oprah Magazine; the Minneapolis Star Tribune; and The Barnes & Noble Review. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.