Stumbling on a Wasp’s Nest

In Ronald Kidd’s new middle-grade novel, a girl comes of age in the civil-rights era

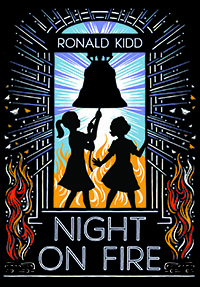

Award-winning Nashville author Ronald Kidd returns to historical fiction in Night on Fire, the story of thirteen-year-old Billie Sims. It’s the spring of 1961, and Billie and her best friend, Grant McCall, spend their time riding bikes, shopping in the local store, and listening to Top 40 records. Everything changes when Lavender Jones, the Sims family’s housekeeper, tells Billie about the Freedom Riders who will be coming to their town of Anniston, Alabama.

Billie and Grant are in the neighborhood store when a “Negro” boy, as the narrative refers to him, accidentally knocks over some cans. Although this is an easy mistake to make amid the overcrowded shelves, the boy’s mishap is met with hostility and thinly-veiled threats by the adults in the store. Grant sticks up for the boy and the store-owner’s daughter tries to help him, but the children are no match for adults whose prejudice is deeply engrained.

Billie and Grant are in the neighborhood store when a “Negro” boy, as the narrative refers to him, accidentally knocks over some cans. Although this is an easy mistake to make amid the overcrowded shelves, the boy’s mishap is met with hostility and thinly-veiled threats by the adults in the store. Grant sticks up for the boy and the store-owner’s daughter tries to help him, but the children are no match for adults whose prejudice is deeply engrained.

Grant’s family has moved to Anniston for Grant’s father to take a job as the lead reporter on the local newspaper. Perhaps because of his status as an outsider, perhaps because of his father’s job, Grant reacts in a way that serves as a catalyst for Billie’s change of perspective—she begins to question Jim Crow practices that until now have been so familiar as to be invisible to her. As Lavender points out, racism is “a disease like mumps or whooping cough. You catch it from your parents and friends. Most people never recover.” Billie starts noticing the subtle and not-so-subtle ways that prejudice is evident in her daily life.

Even so, Billie seems unrealistically ignorant about segregation. She offers to buy Jarmaine, Lavender’s daughter, a milkshake at the local lunch counter and is taken aback when the girl points out that she can’t eat there. And Billie seems never to have noticed that most houses have a front door for white people and a separate “colored door.” But with her new awareness, Billie realizes that for her, the “Colored Only” signs, the separate doors, the separate drinking fountains “were part of the landscape, like sidewalks and traffic lights” and that she “didn’t think about the signs, but Jarmaine had to.” Once her eyes are opened, Billie recognizes the unfairness of these restrictions.

It’s not only a matter of white over black. The whole society is built on strict hierarchies, which Billie has internalized. She starts her story by saying, “I’m not one of those girlie girls. I don’t ooh and ahh. I don’t giggle and blush.” This reduction of females to simpering dolls is common, of course. It would be refreshing to see a “girlie girl” who is also intelligent and brave, but in Billie’s world this isn’t an option. Boys are clearly superior. She is matter-of-fact in noting that her parents wanted a boy, and she tries to compensate for her gender by being a tomboy. And she accepts without question Grant’s right to boss her around, though he is only a month older.

But as with Jim Crow laws, change is afoot in male-female relationships. Billie’s mother has an outside job—unusual for a middle-class family in this era. When Billie’s father gives her a vacuum cleaner for Mother’s Day, Billie’s mother can’t hide her hurt, perhaps foreshadowing a change in their dynamic. Similarly, the girls are almost as excited to see Diane Nash as they are to see Martin Luther King. (With any luck, Kidd’s young readers will want to find out more about this almost forgotten civil-rights leader.)

But as with Jim Crow laws, change is afoot in male-female relationships. Billie’s mother has an outside job—unusual for a middle-class family in this era. When Billie’s father gives her a vacuum cleaner for Mother’s Day, Billie’s mother can’t hide her hurt, perhaps foreshadowing a change in their dynamic. Similarly, the girls are almost as excited to see Diane Nash as they are to see Martin Luther King. (With any luck, Kidd’s young readers will want to find out more about this almost forgotten civil-rights leader.)

And in this rigidly hierarchical society, children are at the bottom of the ladder. History has almost forgotten sixteen-year-old Claudette Colvin, whose refusal to move to the back of the bus predated Rosa Parks’s more famous protest by nine months and whose case went to the United States Supreme Court. The young people in Anniston are similarly ignored by most of the adults.

Still, the children manage to make their mark. When the Freedom Riders’ stop in Anniston is met with violence, young Janie Forsyth quietly goes to their aid. (Janie, a real person later referred to as “the Angel of Anniston,” was one of Kidd’s inspirations in writing this story.) After the brutal treatment of the Freedom Riders in their hometown, Billie and Jarmaine decide to take their savings and go by bus (sitting together) to Montgomery to join the Freedom Riders. There, the two get caught up in history and, in an exciting climax, contribute their small bit to the protest.

It’s difficult to immerse readers in a world at once familiar and different, and Kidd skillfully imparts details about the 1960s with minimal use of the dreaded info-dump. His deftly-salted details of daily life, good and bad, bring the era to life. He offers no easy answers to the issues the novel raises, but—like Billie—readers of Night on Fire will surely be moved to examine their own prejudices and question their assumptions about how others are treated.

Tracy Barrett is a writer who lives in Nashville. Her tenth novel, a young-adult retelling of Cinderella entitled The Stepsister’s Tale, was published in 2014 by Harlequin TEEN.