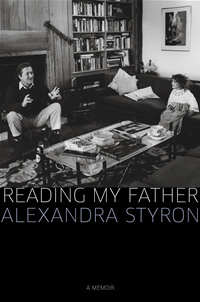

Styron's Choice

In Alexandra Styron’s new memoir, William Styron emerges as a brilliant novelist but an inscrutable father

William Styron, who died in 2006 at eighty-one, was a twentieth-century literary colossus. His three most famous novels (1951’s Lie Down in Darkness, 1967’s The Confessions of Nat Turner, and 1979’s Sophie’s Choice) were critical and commercial blockbusters; Darkness Visible, a memoir chronicling his struggle with severe depression, is astonishing and brilliant, unparalleled in the literature of mental illness.

Except when depression rendered him unable to function, Styron held court at the center of a glittering whirl of social activity—the Styrons drank and made merry with Jim Jones, Lauren Bacall, Teddy Kennedy, Allen Ginsberg, Gore Vidal, John Cheever, Peter Matthiessen, Norman Mailer, Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Miller, Robert Penn Warren,, and James Baldwin, among many others. Styron was a Casanova and a bon vivant; he was also father to four children whom he indulged, ignored, and intimidated at whim. Alexandra Styron, the baby of the family, was born the year Nat Turner was published; in Reading My Father, she aims to merge the tale of a childhood alternately charmed and cursed with a carefully researched exegesis of her famous father’s life and work.

“The monomaniacal (usually male) artist is a familiar image,” she admits. “Even I can see the curious romance in the image of the brilliant writer so consumed with work he barely notices his loved ones mooning around in the shadow of his neglect.” But the genius-as-monster paradigm does not accurately describe William Styron. Though Alexandra spent much of her childhood avoiding her father, after his death she begins combing his archives, reading his books, interviewing friends and family, and ransacking her own memory. Ultimately, her determined efforts bring a kind of peace: “In the end,” she concludes, “he pulled through for me—if not as some idealized version of a father, then as good a man as he could be.” Styron, who will appear at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville October 14-16, answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: As a title, Reading my Father works on two levels: over the course of the book, you come to know both your father himself and his literary legacy. But much of this recognition seems to have occurred after his death. (You stopped reading Sophie’s Choice in adolescence, for example. Having got as far as page 47, you “stood on the back stairs that jutted out over the art room and tried not to throw up on my Bass Weejuns.”) It took twenty-five years for you to come back and finish the book. When did you manage to read your way through his entire oeuvre?

Alexandra Styron: It wasn’t until very recently that I could honestly say I’d read all my father’s major published work. Through a combination of rebellion, disinterest, and sheer laziness I was a latecomer to his novels. In my twenties, I read The Confessions of Nat Turner and Lie Down in Darkness. I didn’t pick up Set This House On Fire till my early thirties. And, yes, it wasn’t until about six years ago that I finally got to Sophie’s Choice. Waiting a while served me well, actually. They are grown-up books and should be read with a little experience under the belt. When I was writing my memoir I realized I’d never read The Long March and In the Clapshack. It was nice to hear his voice again, speaking fresh words into my reader’s ear.

Alexandra Styron: It wasn’t until very recently that I could honestly say I’d read all my father’s major published work. Through a combination of rebellion, disinterest, and sheer laziness I was a latecomer to his novels. In my twenties, I read The Confessions of Nat Turner and Lie Down in Darkness. I didn’t pick up Set This House On Fire till my early thirties. And, yes, it wasn’t until about six years ago that I finally got to Sophie’s Choice. Waiting a while served me well, actually. They are grown-up books and should be read with a little experience under the belt. When I was writing my memoir I realized I’d never read The Long March and In the Clapshack. It was nice to hear his voice again, speaking fresh words into my reader’s ear.

Chapter 16: Your mother, you write, was often absent during your childhood, perhaps her way of coping with some of the more difficult aspects of your father’s personality. Only when you were an adult, and when your father’s depression rendered him cripplingly dependent on her, did the tables turn a bit. Was there a point at which you realized that your research for this book was restoring your mother to you as well as your father?

Styron: I don’t know if the process of writing this book restored my mother for me, but it helped me develop a different and newly admiring perspective on her. As a mother and and a wife now myself, I certainly have a finer appreciation of her compromises and sacrifices.

Chapter 16: Children love their parents instinctively and helplessly, and no amount of growing up (or extracurricular research) can completely undo those primal feelings of attachment. But loving one’s progenitors is very different from actually liking them. After writing your book, do you like your father more than you did growing up?

Styron: Everyone should get the opportunity to make some sort of tour of their parents posthumously. In fact, it should be a required life course, like a kind of middle-aged gap year. Confronting your parents and their stories with a thoughtful and (hopefully) sympathetic eye, as writers do with their characters, can create some very positive distance. Reading My Father certainly did that for me. During the research process, my father became for me a man, separate from my own experience. I developed a much greater understanding of him, which drew out my sympathy and forgiveness. I also began to feel an almost platonic affection for him. I think, if we’d been contemporaries, I’d have wanted very much to be his friend.

Chapter 16: In your epigraph, you quote a poem by Adrienne Rich: “I came to see the damage that was done / and the treasures that prevail.” Near the end of the book, you offer examples of both the damage your father inflicted and the treasure he bestowed. Sitting at your father’s bedside, you recognize for the first time that he favors your sister over you, which, you write, “stung me to my core.” A few pages later, however, you describe your father’s kindness at your wedding, where “he stood and delivered what may have been the last composition he ever wrote, a sidesplittingly hilarious and profoundly loving toast to my husband and me.” Is there any part of that final toast you’d be willing to summarize, with the idea of highlighting “the treasures that prevail”?

Styron: I point out in my book that my father and I really enjoyed each other’s sense of humor. Both of us lean toward the darker side of funny. My father’s wedding toast was really more of a roast of me and my checkered dating history. I had my share of boyfriends. Also, during my last single years, I was everybody’s favorite person to set up. A friend called me the Queen of Blind Dates, and during one particularly ill-advised episode, the moniker was picked up by a British tabloid. So Daddy decided to take this mortifying detail of my past and run with it. He brought the house down. But he also expressed his relief that I’d met my wonderful husband Ed at last, praised me as a writer and daughter, and told me how much he loved me. His fragile state made the whole thing all the more touching. The laughter under the tent turned swiftly to tears. It was a memorable night.

Styron: I point out in my book that my father and I really enjoyed each other’s sense of humor. Both of us lean toward the darker side of funny. My father’s wedding toast was really more of a roast of me and my checkered dating history. I had my share of boyfriends. Also, during my last single years, I was everybody’s favorite person to set up. A friend called me the Queen of Blind Dates, and during one particularly ill-advised episode, the moniker was picked up by a British tabloid. So Daddy decided to take this mortifying detail of my past and run with it. He brought the house down. But he also expressed his relief that I’d met my wonderful husband Ed at last, praised me as a writer and daughter, and told me how much he loved me. His fragile state made the whole thing all the more touching. The laughter under the tent turned swiftly to tears. It was a memorable night.

Chapter 16: Your father’s response to your literary efforts was mixed. He encouraged your early efforts, responding to the first short story you sent him with a long missive that begins, “Dear Al, you really are a very good writer” and ends “More! More! Love, Daddy.” And yet, when you decided to enroll in a creative-writing program, you write, “what had looked like encouragement curled up rather suddenly into something more familiar—indifference.” What do you think he would make of this book, of your commitment to writing, and of your success?

Styron: Many people have said to me, after reading this memoir, “Your father would be very proud of you.” I like to think that but, to be honest, I have no idea. There are some tough truths in this book, and Daddy didn’t like being exposed or made vulnerable to the world. He didn’t take criticism well either. If I had to guess, I think he’d probably be good and pissed on the first read-through, and hopefully move on to respect, and maybe over time even admiration. I do think he’d be glad to see I can put a sentence together. After I’d published my first book, he used to chuckle as he told people what a TV-addicted imbecile I once was and how he worried about how I’d turn out. At least he can rest easily in his grave on that score.

Chapter 16: While researching the book—going through your father’s papers, interviewing his friends, reading his fiction and essays, talking to his editors and to the other members of your family—did you discover anything you wish you hadn’t?

Styron: There is nothing I uncovered in my research that I wish I didn’t know. But I certainly turned up a lot of evidence that confirmed my worst suspicions. The extensive and chaotic manuscripts I found down there gave me a window into his obviously terrible writing frustrations over the last twenty-five years of his life. I also found a lot of material from his youth that made me understand how deeply he must have suffered when his mother died (he had just turned fourteen), and no one gave him any kind of outlet for his grief. I am glad to have learned this information, but it is tough stuff.

Chapter 16: Knowing what you now know about your father’s work and life, is there anything you wish you could ask him? Did writing the book lay his ghost to rest, or did it raise new issues, the possibility of other conversations, that you regret not having had when he was alive ?

Styron: I wish I’d spent more adult time with him. He was so smart, so interesting, and had such a phenomenal memory. If we could have bridged, or put to bed, all the familial mishegoss, I’d have pulled up a chair more often and been a better student.

Chapter 16: You’ve written both fiction and nonfiction. What genre compels you most, and what are you working on next?

Alexandra Styron: I really enjoyed this foray into nonfiction. It’s very satisfying to work from piles of facts, rather than having to invent a plausible reality from whole cloth. But I also get real pleasure from exploring big themes through the crafting of fiction. I have half a novel on my desk, one I put aside to write Reading My Father, that I want to get back to. But right now I’m working on a screenplay, an adaptation of someone else’s memoir. I’ve also been writing several magazine and newspaper pieces, to keep my hand in the game, while traveling these last few months on book tour.

Alexandra Styron will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.