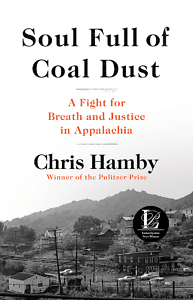

Suffering in Coal Country

Chris Hamby recounts miners’ fight for health benefits in Soul Full of Coal Dust

In Soul Full of Coal Dust, journalist Chris Hamby revisits the stories that won him a 2014 Pulitzer Prize, exposing the treacherous tactics hired hands for the coal industry used to deprive Appalachian miners of health benefits for black lung disease.

Focusing on West Virginia communities where mines offered some of the few well-paid jobs, Hamby describes the legal battles disease-stricken miners waged against their wealthy employers for modest monthly payments of $500 to $800. The weapons lawyers used when they worked for companies like Massey Coal were unconventional – X-ray readings, CT scans, unreported diagnoses. And while company defense attorneys had limitless financial resources and time to appeal, the fragile plaintiffs might be investing the final months of their lives in the fight for justice.

The miners had a champion in John Cline, a carpenter and community activist turned lawyer late in life. Like Erin Brockovich, the legal clerk who forced Pacific Gas and Electric Company to reckon with its role in contaminating a community’s water, and Rob Bilott, the lone lawyer willing to take on DuPont for dumping toxic chemicals in rural West Virginia, Cline was a scrappy outsider who confronted a behemoth.

Cold-hearted coal barons are easy targets. The comedian John Oliver devoted a segment on his HBO show to ridiculing one key figure in Hamby’s book, Massey Coal Company CEO Don Blankenship, who spent a year in prison for conspiring to sabotage health regulations in his mines. But Hamby’s – and Cline’s – painstaking research bravely illuminates the dark cast of characters behind the legal steamroller Blankenship and other company owners used against miners’ health claims.

Bad actors in Soul Full of Coal Dust turn up in unexpected places, such as the radiology department at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the highly regarded Charleston, West Virginia, law office Jackson Kelly, which Hamby describes in a chapter called “The Firm.” It’s not hard to imagine a John Grisham legal thriller based on the deception Cline discovered.

Hamby centers his story on the battle Cline waged on behalf of the Vietnam veteran Gary Fox, who returned to West Virginia after his service and entered the mines to support what mattered to him most, a wife and child. Twenty-five years after he went underground, Fox filed a claim for benefits based on his diagnosis of black lung disease. It was a rude awakening. He couldn’t find a lawyer who would take his case — there wasn’t enough money in it to pay a plaintiff’s attorney — so he represented himself.

Hamby centers his story on the battle Cline waged on behalf of the Vietnam veteran Gary Fox, who returned to West Virginia after his service and entered the mines to support what mattered to him most, a wife and child. Twenty-five years after he went underground, Fox filed a claim for benefits based on his diagnosis of black lung disease. It was a rude awakening. He couldn’t find a lawyer who would take his case — there wasn’t enough money in it to pay a plaintiff’s attorney — so he represented himself.

Blankenship, on the other hand, once bragged that he spent a million dollars a month on lawyers, and his Jackson Kelly attorneys didn’t mind aiming their cannon at a flea. Fox lost, but eight years later, when he was much sicker, he met John Cline. He had found the right man for his case.

Midway through his book, Hamby, a Nashville native who now reports for The New York Times, describes an interlude in his research when he thought he had lost his way. “I was afraid it was a morass in which I would get stuck for months, then emerge with a story that shed little light on anything and was quickly forgotten.” He had met Cline but hadn’t talked to him in a year. His instincts told him to call.

“When we’d talked, he had mentioned a grave injustice he believed he’d uncovered: the leading law firm retained by coal companies to defend benefits claims, he said, was undermining the system by withholding critical evidence.” Cline’s court challenges would lead to a rule change by the U.S. Department of Labor – a Black Lung Benefits Act – that requires medical information disclosure and altered the playing field for coal company lawyers. Hamby’s stories made sure the victory got the attention it deserved. Gary Fox would not live to see the result of his struggle, but a detailed summary of his case was included in the department’s justification for the change.

In journalism, as in most crafts, instincts are essential.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Peggy Burch is now the Arts & Culture editor at The Daily Memphian and a member of the Humanities Tennessee Board of Directors. She holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.