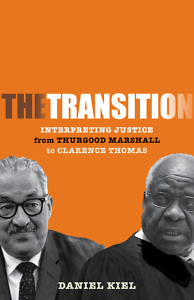

In 1991, President George H.W. Bush appointed Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Thomas replaced Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice in the court’s history and a lion of liberalism. Thomas, however, tilted the court rightward, a shift that keeps reverberating into the present day. In The Transition, Daniel Kiel investigates how these two justices have shaped ideas about race, citizenship, and education in American society. With clarity and insight, he tracks not only their intellectual arguments, but also their personal journeys.

Daniel Kiel is professor at the Cecil B. Humphreys School of Law at the University of Memphis. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he has written widely on the role of the law in school desegregation. He is also the director of The Memphis 13, a documentary film about the first Black students to integrate Memphis City Schools. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Daniel Kiel is professor at the Cecil B. Humphreys School of Law at the University of Memphis. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he has written widely on the role of the law in school desegregation. He is also the director of The Memphis 13, a documentary film about the first Black students to integrate Memphis City Schools. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You argue that Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas had fundamentally different views about American citizenship. How so?

Daniel Kiel: Citizenship and rights for African Americans have always been the most significant challenges to making the principles of the Constitution a reality, and the two justices approached the relationship between government and citizen very differently. Marshall was rooted in acknowledgement of the legally sanctioned and centuries-long denial of citizenship and embraced a justice-centered view that there was an obligation to remedy those wrongs before there would truly be full citizenship. Thomas takes a more individualistic view. His vision centers the citizen’s personal responsibility rather than the government’s obligation to protect citizenship rights.

Chapter 16: Are there common threads in the biographies of Marshall and Thomas? How might their personal experiences explain their ideological differences?

Kiel: The obvious parallel is that both endured both direct racism and the structural disadvantages endemic in our society throughout their lives. For example, no modern Supreme Court justices have been subjected to such open questions of competency to serve on the court.

Yet, though each had to transcend these experiences, they did so a generation apart. The world that Clarence Thomas experienced, particularly once he broke free of the poverty of his earliest years, was made possible by Thurgood Marshall. The doors available to Thomas in college and law school and in his career were simply not open to Marshall. But whereas Marshall always approached his work deeply aware of the stigmas flowing from exclusion, Thomas’ experiences a generation later made him sensitive to racial stigmas resulting from his inclusion in formerly forbidden spaces.

Chapter 16: In recent American history, the appointments and confirmations of Supreme Court justices have engendered deep controversy. How does the 1991 appointment of Thomas fit into this history?

Kiel: There is no less predictable constitutional event than the replacement of a Supreme Court justice, and when the Court is ideologically balanced, the stakes of any new appointment are extraordinarily high. The Thomas appointment tipped that balance decisively with effects being experienced today. His nomination in 1991 began with controversy over Thomas’ views on topics like affirmative action, but it is more remembered today for the allegations of sexual harassment by Anita Hill. Only one confirmation since 1991 has similarly focused on personal conduct (Brett Kavanaugh), but the stakes and partisanship of confirmations have only intensified.

One thing that surprises some people is that Thomas could not have been confirmed without Democrats — 11 voted to confirm him despite the stakes and the harassment allegations. By contrast, only three Republicans voted in 2022 to confirm Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who was far less controversial and whose appointment was unlikely to tilt the court’s ideological balance significantly.

Chapter 16: Their distinct ideas about Black education, you write, “reflected one of the great divides in American constitutional interpretation.” How did each envision the role of the court in addressing race and education?

Kiel: In Marshall’s final dissent as a justice in 1991, he lamented that the court was abdicating its role as “protector of the powerless,” a fitting final phrase from someone who did more to sharpen that role for the court as both lawyer and justice than perhaps anyone in American history. He saw the court playing an important, even central, role in promoting educational justice.

Thomas has taken a very different approach and has been relentlessly skeptical of most efforts to remedy educational disparities and segregation. That includes both restraining courts from crafting effective remedies to educational inequality and hostility toward affirmative efforts by schools and communities to do so. His ideology of colorblindness has triumphed on the current court, which is likely to strike down affirmative action in college admissions this term.

Chapter 16: How might an in-depth look at the life and career of Clarence Thomas shed light on Black conservatism? Is his political philosophy connected to a larger Black experience?

Chapter 16: How might an in-depth look at the life and career of Clarence Thomas shed light on Black conservatism? Is his political philosophy connected to a larger Black experience?

Kiel: One challenge with this project has been to disconnect Thomas’ ideas from the very intense personal opinions many people have of him. But there has always been a current of conservatism within broader conversations about the best path toward Black uplift. Ideas of personal responsibility and deep distrust of government (even to the point of promoting separatism) that Thomas embraces connect to other Black thinkers through American history.

One thing that is different with Thomas, though, is that he has become affiliated with a major political party that has seemed to work against racial justice for the past half-century. It is this disconnect that has caused such a substantial rift between Thomas and so many African Americans.

Chapter 16: Near the end of The Transition, you connect the protests of 2020 and 2021 to the ideological banners of Marshall and Thomas. How can the philosophies of the two Supreme Court judges help explain our current political polarization?

Kiel: For me, it comes back to the citizenship question. So much of our current moment is about the proper role of government, the appropriate relationship between citizens and government, and even the obligations that citizens owe one another. Those are not only questions about Black citizenship; they go to the very heart of defining what it means to be American.

The highly individualistic philosophy of Clarence Thomas sees the highest form of citizenship as being freedom, including freedom from government. Taken to an extreme, this might transform into skepticism of government legitimacy or a revolt against government, emotions on display on January 6, but also in resistance to pandemic regulations.

For his part, Thurgood Marshall’s career is a demand that Black citizenship matters, but he also had a gift for connecting the fates of any group of Americans to the entire American project — when any group of citizens demand justice from government, as so many have in recent years, they do so under a banner stitched by Thurgood Marshall. These impulses on citizenship are not always in opposition, but like so much in the current moment, they have come to seem incompatible in a world of absolutes.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.

Tagged: Q&A