Surviving Slavery

An enslaved family follows a treacherous path to freedom in rural Alabama

In Red Clay, Charles B. Fancher explores the fraught ties, sometimes intimate but always potentially violent, between enslaved people and plantation owners at the close of the Civil War and the dawn of Reconstruction.

Inspired by research into his own family history, Fancher delivers a briskly paced, deftly plotted tale, set on a remote Alabama plantation called Road’s End near the fictional town of Red Clay, Alabama.

It opens in 1943, at the funeral of Felix Parker, whose parents were the enslaved valet and cook of the planter John Robert Parker. A mysterious elderly white woman shows up at Felix’s service, then presents herself at the family’s house, explaining to his granddaughter that she and Felix knew each other as children because once, “my family owned yours.” The women agree to share what they know about his life, a device that frames the story.

That story begins in 1864, when 8-year-old Felix is taken by the plantation owner on what’s presented as a trip to town but ends in a shocking death, leaving the boy with a terrible secret that would devour the white family’s wealth if he failed to keep it.

Felix’s parents have already sacrificed too much to the owner’s financial needs — their two older children, a 15-year-old boy and 13-year-old girl, have been sold “like a litter of hound dog pups” to a Mississippi landowner, and Fancher skillfully creates the suffocating atmosphere under which the bereft parents live in close quarters, forced to feign duty and respect, with the people who caused their suffering.

The horrors of slavery have inspired numerous important novels over the years — from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, to Margaret Walker’s Jubilee (1966), Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family (1976), Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), and Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad (2016). In all, the fear of violence disfigures victims and deforms the hearts of their warders. In Red Clay, Fancher dissects the ways John Robert Parker and his two sons adapt to and excuse their own cruelty. Claude, the son who takes over the plantation after his father’s death, is initially an “average” man, “neither an egalitarian nor an abolitionist,” who also “saw no reason to be disrespectful or unpleasant to anyone.” That will change.

The mysterious woman at the funeral is Claude’s sister, Adelaide, who humiliated Felix when they were children by feeding him table scraps out of her hand. Because of her childish intuition that he’s not telling all he knows about the death he witnessed, he’s sent to field labor at the age of 8. Fancher weaves a complex mix of good and evil into Felix’s ties to the planter’s children. Claude rescues Felix from the field and makes him a carpenter’s apprentice, providing him with a skill that gives him a lifetime of financial stability. But in the bewildering atmosphere of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, when Claude becomes a threat, it’s Adelaide who steps in to help.

The mysterious woman at the funeral is Claude’s sister, Adelaide, who humiliated Felix when they were children by feeding him table scraps out of her hand. Because of her childish intuition that he’s not telling all he knows about the death he witnessed, he’s sent to field labor at the age of 8. Fancher weaves a complex mix of good and evil into Felix’s ties to the planter’s children. Claude rescues Felix from the field and makes him a carpenter’s apprentice, providing him with a skill that gives him a lifetime of financial stability. But in the bewildering atmosphere of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, when Claude becomes a threat, it’s Adelaide who steps in to help.

Fancher’s attention to the sensory details of agrarian life is among the pleasures of reading Red Clay. Felix’s mother makes sumptuous meals, a breakfast of “fried ham, a platter of steaming soft-scrambled eggs, and a bowl of hot grits with a dollop of yellow butter melting in its center,” and a Thanksgiving turkey “scenting the air with the aromas of herbs, spices, nuts and fruit….” Felix goes to sleep to the sounds of “an owl hooting, field mice scurrying across the roof, and from somewhere down the row of cabins, a home-brew-fueled argument between two men over a woman they both wanted.”

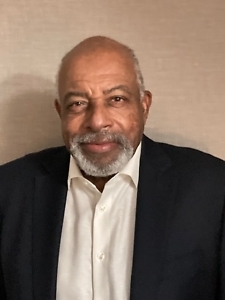

Fancher, who began his journalism career at WSM-TV in Nashville, worked as a reporter and editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer and Detroit Free Press, then as a communications executive and faculty member at Howard and Temple universities. Fancher’s great-grandfather, who was born into slavery in Alabama but whose family flourished after the Civil War, inspired the character of Felix. In an afterword, the author describes his mother’s picture of his ancestor as “a fellow with a roguish streak, including a taste for good liquor and an eye for the ladies.” They are traits that survive in Felix.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis and the art and culture editor for The Daily Memphian, Peggy Burch holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.