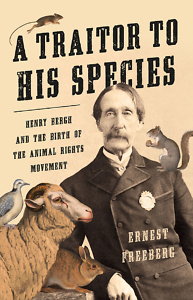

Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Man is the cruelest animal.” Whether that statement is true is a debate best left to philosophers. But it cannot be denied that human cruelty exists and that abuse of animals is one of the most common manifestations of that regrettable trait. In A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement, historian Ernest Freeberg explores the founding and early years of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). It is a tale of decency confronting villainy, set against a backdrop of a nation undergoing technological and moral revolutions that shaped the modern world.

The American animal rights movement began in post-Civil War New York, a city teeming with humans and animals. Henry Bergh, an independently wealthy, middle-aged, failed artist — his desire to be a playwright was much greater than his talent — decided he’d had enough of seeing animals abused for the profit, feeding, and entertainment of humans. His crusade for justice started in Russia, where he served as a diplomat during the Lincoln administration and witnessed the all-too-common beatings of horses. Benevolence was in vogue at the time, creating an atmosphere in which age-old abuses of humans could be abolished.

“On both sides of the Atlantic,” Freeberg writes, “reformers translated this sentiment of compassion into institutions to prevent suffering — of prisoners, the poor, the deaf, the blind, the aged, and the enslaved.” In 1866, Bergh founded the ASPCA in his native city, believing that the spirit of reform should be applied to the “dumb animals” that made human existence possible.

Nineteenth-century America was powered, quite literally, by animals. Horses by the thousands pulled cargo wagons, barges, carriages, and trolley cars. And beyond simple horsepower, animals were used for food, clothing, and myriad consumer goods, most of which were produced within city limits at local slaughterhouses and rendering plants, where virtually every part of an animal was put to use. Add in packs of dogs, millions of rats, cats, birds, and other creatures and it is not hyperbole to state that people in urban areas interacted with more animals on a daily basis than their rural counterparts. Cities were full of the sights, sounds, and smells of every kind of beast, including many of the two-legged variety.

Bergh and his agents, empowered by the State of New York’s anti-cruelty law, confronted and arrested anyone they found to be abusing — not using, but abusing — any animal. Freeberg notes, “While defending animals, Bergh saw the darkest side of human nature — the desperate poverty, the sadism, the ignorance and indifference to suffering that motivated so many of these acts.” He battled industrialists, teamsters, purveyors of dogfights, and entertainers who displayed animals to a curious public. A frequent target was the showman P.T. Barnum, whose museums exhibited exotic animals by the hundreds, sometimes in inhumane conditions. Bergh and Barnum sparred often and came to respect one another, with Barnum not only attending Bergh’s funeral in 1888 but donating money to a memorial for the activist.

Ernest Freeberg is department chair of history at the University of Tennessee and has previously written award-winning books about dissenter Eugene V. Debs and the changes wrought upon the world by Thomas Edison’s electric light. In A Traitor to His Species, Freeberg skillfully portrays Henry Bergh as a remarkable, little-known exemplar of the 19th-century reform movement, a man who suffered much ridicule yet found success in a just cause. But Freeburg also honestly addresses Bergh’s flaws. He was a privileged aristocrat who believed in corporal punishment and was deeply prejudiced against immigrants. He was zealous and sometimes callous in his cause and could antagonize even his supporters by prosecuting seemingly minor crimes against unpopular animals, such as the blood sport known as ratting, in which spectators bet on how many rats a dog could kill. Bergh was an absolutist, defending all animals.

Ernest Freeberg is department chair of history at the University of Tennessee and has previously written award-winning books about dissenter Eugene V. Debs and the changes wrought upon the world by Thomas Edison’s electric light. In A Traitor to His Species, Freeberg skillfully portrays Henry Bergh as a remarkable, little-known exemplar of the 19th-century reform movement, a man who suffered much ridicule yet found success in a just cause. But Freeburg also honestly addresses Bergh’s flaws. He was a privileged aristocrat who believed in corporal punishment and was deeply prejudiced against immigrants. He was zealous and sometimes callous in his cause and could antagonize even his supporters by prosecuting seemingly minor crimes against unpopular animals, such as the blood sport known as ratting, in which spectators bet on how many rats a dog could kill. Bergh was an absolutist, defending all animals.

Abuse of animals in Bergh’s time was rampant and often gruesome, and Freeberg does not flinch in describing the horror. Much of the worst cruelty ended only with advances in technology that relieved animals from powering the economy and allowed more humane food processing. But even under reforms fought for by Bergh and his allies, abuse continues in the present day, with stories of illegal puppy mills and mistreatment of horses regularly appearing in the press. An important difference is that today the perpetrators are almost universally condemned, their brutality recognized as a crime against the whole of society. It is perhaps Bergh’s greatest legacy, that in fighting the torture of animals he helped people know their better selves. The cruelty, as Freeberg explains, “was making men worse — more brutal, callous to suffering.” Ending the abuse, Bergh believed, would improve the lives of humans as well as animals.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.