Tell About the South

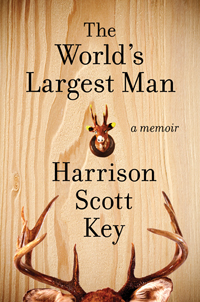

Harrison Scott Key’s new memoir attempts to reconcile the man he is with the man he sought to escape—his father

Midway through William Faulkner’s Absalom Absalom!, Shreve McCannon starts throwing questions at his Harvard roommate, the Mississippian Quentin Compson. “Tell about the South,” he demands. “What’s it like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they live at all.”

The scene takes place in 1910, and Faulkner wrote the novel in 1936, but Harrison Scott Key knows just what it’s like to be on the receiving end of such questions. Early in his new memoir, The World’s Largest Man, he discusses how hard it is to talk with non-Southerners about the complexities of the South. “It is not easy explaining all this to educated people at cocktail parties,” Key writes, “so instead I tell them that it was basically just like Faulkner described it, meaning that my state is too impoverished to afford punctuation, that I have seen children go without a comma for years, that I’ve seen some families save their whole lives for a semicolon.”

It’s too bad Compson, who ended up drowning himself in the Charles River, didn’t have Key’s gift for playing pain for gags—he might have lived longer. Indeed, like many of the great Southern humorists, Key relies on wit to bridge the deep emotional fissures that many people, at least of the thinking persuasion, have to cross when trying to reconcile the historic evils of the South with their own enduring love for it.

It’s too bad Compson, who ended up drowning himself in the Charles River, didn’t have Key’s gift for playing pain for gags—he might have lived longer. Indeed, like many of the great Southern humorists, Key relies on wit to bridge the deep emotional fissures that many people, at least of the thinking persuasion, have to cross when trying to reconcile the historic evils of the South with their own enduring love for it.

The World’s Largest Man centers on Key’s relationship with his father, an arrogant, abusive, and at times absurd Mississippian given to “swatting a fly that wasn’t there and staring off toward horizons of land he didn’t own.” When Key was still a small child his father moved the family from Memphis, where Key was born, to a small town near Jackson so that Key and his brother could grow up as proper Southern boys, hunting, fighting, and digging endless holes around the yard.

Except that Key wasn’t especially given to hunting, or fighting, or digging. He read the World Book encyclopedia, volume by volume, cover to cover. He preferred shopping with his mother to the long days spent camouflaged behind duck blinds and up in trees, rifle in hand, that his father forced on him. Sitting in his stand, in the early morning darkness, “I looked into the sky and could see nothing but Orion,” he writes. “We were doomed to hunt forever, he and I.” Eventually, he brought books with him to while away the time; he knew he wouldn’t hit anything anyway.

And so Key stumbled through his adolescence, fearing and loving his father, but mostly just trying to figure him out.

What becomes clear is that for all the elder Key’s redneck bumptiousness, he was much less of a redneck than many of the family’s neighbors, who lacked teeth and jobs and homes without wheels. The Keys lived in an actual house; Mr. Key had an actual job as an asphalt salesman. And that bothered him deeply. He was Southern, but in some basic way that may have mattered only to him, he was no longer of the South.

Key recalls his father’s struggles with the restrictions placed on him by a society that had come to recognize only his ability to sell tar, not his manhood, and his rage against his boss, and books, and the Boy Scouts, and any sign of civilization that he stumbled across. But he also developed a grudging respect for minorities and technology, if only because he could recruit Caribbean immigrants as ringers for his baseball team and because the iPhone has a cool compass function.

Key has a gift for the well-turned, earthy description –the smell of a cow giving birth is “regal in its unpleasantness”; the process of dressing a dead animal is “pretty much the opposite of dressing.” His father beat him with a hairbrush, as punishment, so hard that he left behind “a puddle of son,” an image both achingly funny and achingly sad. Later, as an adult, Key tells a neighbor, “Stop burning your trash. This is not a Cormac McCarthy novel!”

Key has a gift for the well-turned, earthy description –the smell of a cow giving birth is “regal in its unpleasantness”; the process of dressing a dead animal is “pretty much the opposite of dressing.” His father beat him with a hairbrush, as punishment, so hard that he left behind “a puddle of son,” an image both achingly funny and achingly sad. Later, as an adult, Key tells a neighbor, “Stop burning your trash. This is not a Cormac McCarthy novel!”

At times, though, the humor can be overwhelming, especially when most of it relies on bathos. “Thank you to God, who made trees, so we could have books and napkins,” Key writes in his acknowledgements—a funny line, but the sort of easy funny that gets old quickly.

Fortunately Key is made of stronger stuff, and it comes through in his later chapters, as he grows up and has a family of his own, as his father grows old and frail. He confronts a dilemma that all men face, if they are lucky enough to see their fathers through to old age: how can a man still be a father, once synonymous with power and violence and fear, and yet be so small and, in the end, helpless?

Like father, like the South. Key has made his way in the world; he teaches English at the Savannah College of Art and Design. In time he reached escape velocity from his father’s orbit but also from a South that punished him for reading, for thinking broadly, for having interests beyond hitting people and killing things. And yet, looking back, he realizes he was made from the very place and man he tried to leave.

In that paradox he feels the need to explain them to everyone, but to no one more than to himself. “The South,” Key writes, “is a strange place, one that can’t be fit inside a movie, a place that dares you to simplify it, like a prime number, like a Bible story, like my father.”

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.