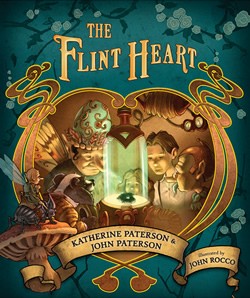

Tender Hearted

Legendary children’s author Katherine Paterson and her husband, John Paterson, revive a forgotten fairy tale

Once upon a time, there lived a Stone Age English tribe whose “mystery man,” Fum (a cross between a bard, priest, and medicine man, in case you were wondering), had a way with flint. At the behest of a power-hungry would-be chief, Fum makes a heart-hardening charm—the Flint Heart—and sells it for thirty-two sheep and thirty-two lambs. What happens next feels deliciously familiar, as all good fairy tales must. The Flint Heart wreaks havoc through its owner, until (finally) it shares his grave. There it lies, never changing, for five thousand years, as potently evil as the day it was struck.

Readers certain they’ve come across a modern reincarnation of some old English tale—The Lord of the Rings leaps instantly to mind—are only partially correct. For The Flint Heart, co-written by Katherine Paterson and her husband, John, is in fact an abridged and updated version of a book by Eden Philpotts (a once-renowned and now mostly-forgotten British author of the early-twentieth century), originally published in 1910. “One of John’s favorite writers is Margaret Mahy, and Margaret was asked, along with many others of us, ‘What 20th century book do you want to make sure is available for children in the 21st century?’ And Margaret said The Flint Heart, of which we had never heard,” Katherine Paterson recently explained in an interview with TeachingBooks.net. “So John made it a personal quest to find himself a copy of this long-out-of-print book. He read it, and he really loved it. He tried to get it republished as it was, but no one would. It is basically a wonderful, wonderful story, but it’s just got too many things in it that would either be boring or would just not make any sense to a modern reader. So we put our heads together and decided we would freely abridge it and take out what was inaccessible and try to turn it into a story that could be read and enjoyed.”

Katherine Paterson is one of the most acclaimed children’s authors alive, with two Newbery Medals (for Bridge to Terabithia in 1977, and Jacob Have I Loved in 1981), two National Book Awards (for The Master Puppeteer in 1977, and The Great Gilly Hopkins in 1979) and a host of other awards for both individual novels and for her body of work, including the Hans Christian Andersen and Astrid Lindgren awards, the most prestigious and biggest prizes in children’s literature. But she is also a devoted advocate for children’s literature in general, and served as the second National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

Katherine Paterson is one of the most acclaimed children’s authors alive, with two Newbery Medals (for Bridge to Terabithia in 1977, and Jacob Have I Loved in 1981), two National Book Awards (for The Master Puppeteer in 1977, and The Great Gilly Hopkins in 1979) and a host of other awards for both individual novels and for her body of work, including the Hans Christian Andersen and Astrid Lindgren awards, the most prestigious and biggest prizes in children’s literature. But she is also a devoted advocate for children’s literature in general, and served as the second National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

Her generosity toward other authors thus finds a perfect outlet in The Flint Heart, which allows her to exercise her own creativity while bringing a forgotten book back to life. Paterson and her husband have collaborated before: “It’s a lot more fun than wallpapering with him,” she jokes in interviews. Before The Flint Heart, the two worked on three books together: Consider the Lilies (he did all the research; she wrote), Images of God (both wrote, then each rewrote the other), and Blueberries for the Queen (he wrote first, then she rewrote). “With The Flint Heart,” Katherine told TeachingBooks.net., “John went through it chapter by chapter and decided what was vital to retain and what had to go in order to make it accessible.” The book still sounds like Eden Phillpotts, she noted, “because we used his language wherever we could. And when we couldn’t, we imitated it because we wanted to have that early 20th century voice come through.”

And it does, in spades. Though the writing has been streamlined, the story has not been dumbed down to reflect modern notions of what’s proper literature for the young. This faithfulness to the complicated original is characteristic of Katherine Paterson, whose novels frequently address difficult, even wrenching topics (the death of a child in Bridge to Terabithia, for instance). The part of The Flint Heart that’s set in Edwardian England—the “modern” part of the story, in other words—begins when the evil talisman is accidentally unearthed, and a kind, benevolent farmer and father of nine, Billy Jago, unwittingly pockets it. Instantly, he turns cruel, and his children are horrified, saddened, and shocked. “But you won’t be surprised,” Paterson writes, “because you’ve already guessed that the Flint Heart in Billy Jago’s waistcoat pocket was bubbling away with wickedness, delighted to be at work again.”

And it does, in spades. Though the writing has been streamlined, the story has not been dumbed down to reflect modern notions of what’s proper literature for the young. This faithfulness to the complicated original is characteristic of Katherine Paterson, whose novels frequently address difficult, even wrenching topics (the death of a child in Bridge to Terabithia, for instance). The part of The Flint Heart that’s set in Edwardian England—the “modern” part of the story, in other words—begins when the evil talisman is accidentally unearthed, and a kind, benevolent farmer and father of nine, Billy Jago, unwittingly pockets it. Instantly, he turns cruel, and his children are horrified, saddened, and shocked. “But you won’t be surprised,” Paterson writes, “because you’ve already guessed that the Flint Heart in Billy Jago’s waistcoat pocket was bubbling away with wickedness, delighted to be at work again.”

This confiding tone and ebullient language make The Flint Heart a dark and thrilling joy to read. Though it’s aimed at middle-grade readers, younger children will surely relish hearing it read aloud. And as is true of the best read-aloud books, there’s plenty here to engage grown-ups, including a pixie named De Quincey who quotes Tennyson and Milton and laments, “I am not appreciated. Who cares for the music of English prose nowadays?” The book is pitched both high and low, following the exhortation of a pixie in the story named Hans Christian Andersen: “Anybody who uses a word of more than three syllables in a fairy story doesn’t know his business.” Katherine and John Paterson certainly know theirs; this eloquent retelling is a perfectly lovely homage to a forgotten children’s book—a book in which, it no doubt goes without saying—they all live happily ever after.

Katherine and John Paterson will discuss The Flint Heart at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 13 at 9:30 a.m. in the War Memorial Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public.