The Art of Recovery

A new book by the Creative Arts Project spotlights the healing power of art

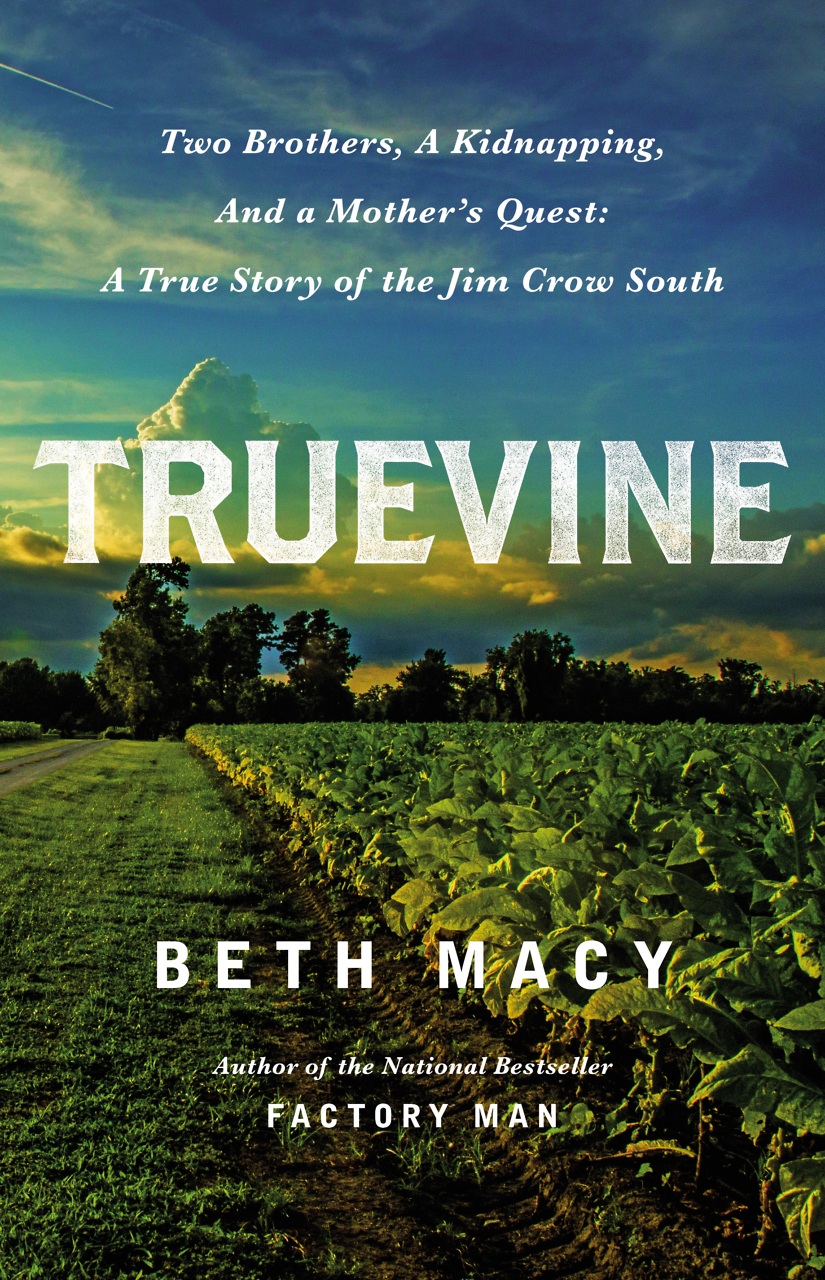

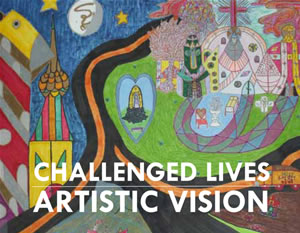

Challenged Lives: Artistic Vision, a colorful new art book by the Creative Arts Project, is bringing attention to a number of Middle Tennessee creators, showcasing their work as well as their personalities and their thoughts on the creative process. Years in the making, it’s the latest effort by this Nashville-based organization to raise awareness about mental illness and addiction, and to draw attention to the life-changing benefits of art therapy.

The book features interviews with nearly thirty artists who have been challenged by mental illness or addiction disorders. Telling their stories in their own words, the Challenged Lives artists are at turns humorous and humble, insightful and just plain excited. The book is packed with reproductions of their work, and the therapeutic benefits of it is a message that comes through loud and clear in both the vivid imagery and the revealing text.

Jane Baxter, director of the Creative Arts Project, recently answered questions via email about the book, the artists it showcases, and the value of creative therapy.

Chapter 16: Tell us a little bit about this program.

Baxter: The Creative Arts Project is sponsored by the Middle Tennessee Mental Health and Substance Abuse Coalition, a nonprofit organization made up of mental-health professionals, advocates, consumers, and family members who work together to raise awareness and to reduce stigma against those living with these disorders. The mission of the Coalition is connecting artists and communities to promote understanding, acceptance, and success of people in recovery.

Chapter 16: How did the Challenged Lives: Artistic Vision project get started?

Baxter: About one in five people will experience a mental illness in their lifetime; over half of the persons with a mental illness also have a co-occurring addiction disorder. We felt we were only partway reaching the heart of the public to reduce stigma and bring acceptance. One of our members, Louetta Hix, suggested that we use art as a means to catch the public’s attention. In 2005, we applied for grants from the Tennessee Arts Commission and the Metro Nashville Arts Commission to hold art classes in peer-support centers, and we recruited art from the art classes to show in libraries, art galleries, and churches.

Baxter: About one in five people will experience a mental illness in their lifetime; over half of the persons with a mental illness also have a co-occurring addiction disorder. We felt we were only partway reaching the heart of the public to reduce stigma and bring acceptance. One of our members, Louetta Hix, suggested that we use art as a means to catch the public’s attention. In 2005, we applied for grants from the Tennessee Arts Commission and the Metro Nashville Arts Commission to hold art classes in peer-support centers, and we recruited art from the art classes to show in libraries, art galleries, and churches.

Chapter 16: The shows have been rather high-profile, part of the ongoing dialog in Nashville’s art scene.

Baxter: When we started the project, we were focused on public awareness and stigma reduction. After a couple of years, we could see that there was clearly another dynamic at work—a transformation in the way the artists perceived themselves; they had a new self-assurance, self-respect, and self-confidence.

Chapter 16: You’ve put together literary publications in the past. Why change to a book that focuses on visual art?

Baxter: We were inspired to model this book after a publication from Germany featuring a group of artists with similar mental-health issues who were featured in a collection of art that traveled the nation. Since we have minimal funding and are a volunteer group, it has taken a long time to produce the book on the artists.

Chapter 16: Half of the book is made up of interviews with the artists, put together by Kathleen Makara, who has a master’s degree in community development. How did Kathleen get involved?

Baxter: Kathleen was ready to do a field study for her master’s degree, and a grant came up through the Tennessee Disability Coalition to pay the summer stipend and travel costs for Kathleen to travel to Middle Tennessee to do the interviews, take pictures, and write the stories. She has a warm personality, and the artists truly enjoyed their interviews and consider Kathleen their friend.

Chapter 16: The interviews manage to be both succinct and thorough, and they focus on the creativity of the artists. Most make no specific mention of mental illness or chemical dependency.

Baxter: The artists are persons first. We wanted to promote their success as artists. We felt their diagnosis was not relevant to their success as artists.

Chapter 16: Some of the artists have actually found degrees of professional success: creating a logo design or painting the winning design for a conference t-shirt. How much has your program been involved in promoting their work beyond the classroom?

Baxter: We send out opportunities to enter local, state, or national competitions, such as Disabilities Conferences, national calendar art calls, state or national mental health conferences. The artist will tell us what artwork they want to enter. If there is already a picture, we will prepare it for the competition. If they don’t have a picture, we will photograph their artwork and format it according to contest specifications, and send it on its way to the sponsors.

Baxter: We send out opportunities to enter local, state, or national competitions, such as Disabilities Conferences, national calendar art calls, state or national mental health conferences. The artist will tell us what artwork they want to enter. If there is already a picture, we will prepare it for the competition. If they don’t have a picture, we will photograph their artwork and format it according to contest specifications, and send it on its way to the sponsors.

Chapter 16: And what about the exhibits that you put together yourselves?

Baxter: Our project organizes a series of exhibits from Mental Illness Awareness Week in October through the late spring, taking the prior year’s artwork to public venues such as libraries, galleries, churches, performing arts centers, art leagues, and university campuses. We have done public murals in different community centers on permanent display. We look for places to have the public see the art and read about the artists.

Chapter 16: How were the artists featured in the book chosen?

Baxter: We formed a jury of local artists recommended by Andee Rudloff of the Frist Center for the Visual Arts. The panel was provided images of work by around sixty of the artists, and [they] chose thirty-five artists to [invite].

Chapter 16: The interviews in the book reveal the very sophisticated understanding of the creative process that these artists have; they speak about the inner life of an artist with a depth and clarity that might surprise readers. How do these artists learn to manage their external lives by becoming such experts at navigating their internal lives?

Baxter: I would have to talk further with artists on this question, but I observe from what they say that art brings them to a peaceful place, away from pressures and stress, and that they gain a positive feeling about themselves by producing art that pleases themselves and others.

Chapter 16: The artists in the book range from grandmothers to former bobcat hunters to trained artists with M.F.A. degrees. What role does art making play in creating a community among such a diverse group?

Baxter: Their common experience of having their life changed with the onset of their mental illness or addictive disorder brings the individuals into a community. Their common sense that creating art is a safe zone in which they can speak through their art, reflect their view of the world, share happy times, share images that they enjoy, bring pleasure to others through their art, all come to form bonds between them.

To find out more about the Creative Arts Project and Challenged Lives: Artistic Vision, click here.