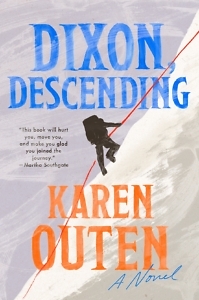

The Beauty in Descending

Karen Outen’s Dixon, Descending brings to life two brothers with a costly ambition

In a place where people stand on top of the world, far above the clouds, Karen Outen’s debut novel Dixon, Descending brings two Black male characters face to face with the reality of their audacious, unapologetic ambition. It is nearly impossible for non-alpinists to climb to the top of Mount Everest and exceedingly rare for Black people to do so; brothers Dixon and Nate set out to be the first two African American men to achieve that feat.

But the brothers discover in the freezing winds of the mountain that to summit Everest is more than a check on a bucket list. It is an ascent to a living place. This mountain in her danger serves as judge and jury. There is no predicting who will summit and who will not, and Dixon and Nate are no exception — as Dixon, the novel’s protagonist, will come to understand: “Later, he would remember the many ways the mountain had revealed herself, and he would wonder: why did they excuse her fits of temper, cajole and caress and long for her, as if they would be spared?”

For months, the brothers train relentlessly. Dixon was seconds away from becoming an Olympic runner in his youth, and even that level of fitness couldn’t compare to the rigor demanded of an Everest hopeful. He and Nate go beyond their limits, then farther still, until the day comes that they feel ready.

After landing in Nepal, Dixon and Nate are immediately confronted with their own lack of preparedness. When they meet real alpinists in the hotel bar, they see that the people who climb in the Himalayas as a way of life are a different breed entirely. Instead, Dixon and Nate are dubbed “clients,” people with the significant financial means to pay Nepalese sherpas and alpine guides to take them to the summit. Seeing the cockiness and blind self-assuredness of their fellow clients paints a stark dichotomy with the alpinists they meet.

While Nate remains focused on their original goal, Dixon finds himself drawn by the philosophy of the alpinists, who see the mountain is a living, breathing being who can accept or reject them. “You think she’s inanimate, that she’s not paying you any mind,” Dixon says later, recalling the Everest experience. “But the sherpas, they tell you quick when you get there ‘Respect Mother.’ They ask her permission to climb…She’s watching, seeing what she brings out in you.”

From the trek to base camp and the first two acclimatization treks to camps at higher elevation, the rigor of their climbs only foreshadows the reality of life above 20,000 feet, with little oxygen and unforgiving, brutal conditions. Dixon and Nate stick together, lending one another a hand and pushing each other toward the top.

That is, until Everest has her way with them and tragedy strikes.

In the aftermath of his summit attempt, as the title foretells, Dixon descends into a battered state of being. His physical body wrecked by the extreme cold and harsh conditions, his mental health spiraling, he spends month bedridden. Then, eager to find some sense of autonomy again, he returns to his job as a child psychologist at an all-boys’ school.

In the aftermath of his summit attempt, as the title foretells, Dixon descends into a battered state of being. His physical body wrecked by the extreme cold and harsh conditions, his mental health spiraling, he spends month bedridden. Then, eager to find some sense of autonomy again, he returns to his job as a child psychologist at an all-boys’ school.

In the months before his leave of absence to train for the summit, Dixon noticed a student, Marcus, struggling to adjust due to the unrelenting pressure of a bully named Shiloh. After Dixon returns, it becomes clear that Marcus is in no position to fend for himself, and Dixon takes the boy under his wing.

The attachment to Marcus becomes another layer in Dixon’s complex healing process. He feels like a father figure to Marcus but can’t reduce his understanding of Shiloh to that of a two-dimensional, flat villain. In the moments he does regard this child in such an unredeemable light, Dixon’s memories of the most difficult moments on Everest come back to mind and he sees his own fragility in stark form.

The complicated reality is that both boys struggle with their self-understanding as they grow into young Black men. Shiloh’s antagonism toward Marcus is an attempt to ignore his own wounds, deeper than many will ever understand. When Marcus is seriously injured from an assault, Dixon has to face the intertwining of his own painful recovery from the traumatic experiences on Everest with his personal and professional ties with these children in need of an advocate.

As the story comes to a close, Dixon reveals a secret just in time to accept what is rightfully his and mourn all he has lost. With the truth out in the open, Dixon’s story compels readers to consider the price of ambition and what it means to face our own mortality.

Sarah Stewart is a writer from Nashville. Her work has appeared in Nashville Scene, She Reads, and The Beet. In her free time, she writes about her journey to every country in the world on From the Aisle Seat.